Future of Winter Olympics Skating On Thin Ice

by AMANDA GRIFFITHS

Our office mascot Joey getting ready for the opening ceremonies in PyeongChang

Winning gold at the Olympics is touted as the pinnacle of athletic achievement. Every four years, we hear stories of athletes’ endurance and perseverance while we watch all of their dedication pay off. We experience these feats in real time- feeling the nerves and tension of competitors as they either realize their greatest potential or fall short of their goals. But many of these achievements require one crucial component– snow!

Climate Change and the Winter Games

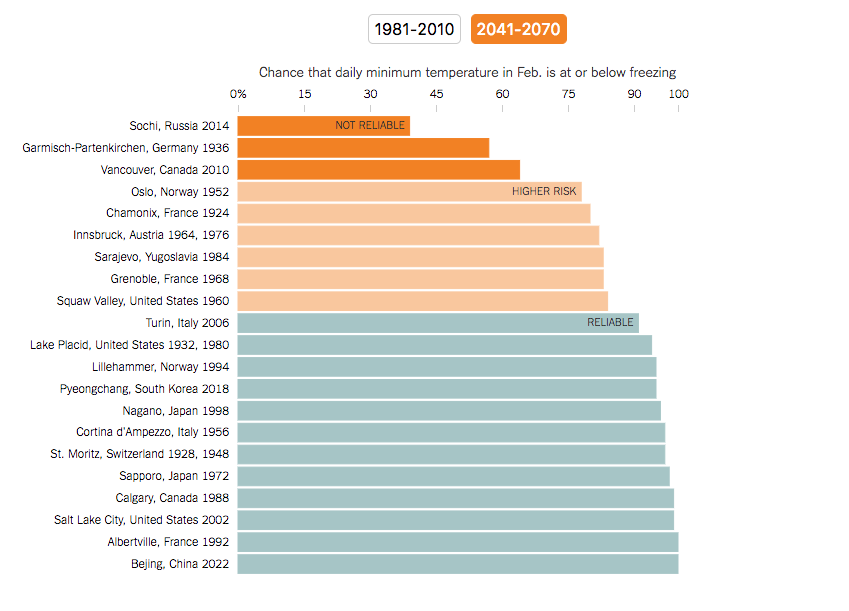

In the Winter Olympics, sporting events showcase brilliant mountainsides covered in fresh snow. But what will happen to these mountainside locations in coming years? Will climate change impact the number of cities able to host the games? As temperatures warm, snowfall is decreasing and snowmelt is increasing in mountains across the globe. By mid-century, nine previous host cities will no longer be able to reliably host future games. While some locations can compensate for lower snow yields with artificially made snow, those machines are only effective when temperatures remain below freezing. A larger problem presents itself when temperatures become too warm to sustain snow on mountainsides.

In the 2010 Vancouver and 2014 Sochi Olympics, above average temperatures left organizers scrambling to cover bare mountainsides. In some cases, hay was laid underneath snow from higher elevations to cover athletic courses. And while artificial snow can improve the appearance of ski slopes, athletes have complained about the texture and spread of it impacting their performance and safety. During qualifiers for the half-pipe snowboarding event at the Sochi games, more than half of the athletes fell.

Source: New York Times, Of 21 Winter Olympic Cities, Many May Soon Be Too Warm To Host the Games

In future years, climate change will disqualify a number of prior hosts from hosting again. According to research conducted at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, models predict that, some time between 2041 and 2070, Vancouver, Squaw Valley, Oslo, and other cities that have hosted the games in the past will simply not sustain cold enough winter temperatures to host again. Three past hosts–Sochi, Russia, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany and Squaw Valley, United States–are unlikely to be able to reach 30 cm of snow even with artificial snowmaking. Athletes are already being forced to seek snow before going for gold. Melting snowcaps are forcing winter athletes worldwide to travel further to find good powder, ironically compounding the effects of climate change by emitting more carbon.

Some Winter Olympic athletes have become vocal advocates for climate action. American cross-country skier Jessie Diggins, for example, has remarked, “You only get one earth to live on, and you have to breathe the air that is on this earth. We have to do it in a way that doesn’t hurt families economically, which is why I’m supporting the carbon fee and dividend solution, because it puts a fee on carbon and returns the revenue to households.” Team Great Britain snowboarder Aimee Fuller trains annually in Switzerland, where snowfall has been getting noticeably sparser. She has noted that, “Snowboarding is really susceptible to the impact of climate change and we can see the impact on our sport in the mountains on a daily basis.” Winter athletes are at the frontlines of climate change, and the attention they receive on the international stage presents opportunities to advocate for global climate action.

The Local Snow Economy

On-site wind turbine at Bolton Valley, Photo by Justin Cash. From last year’s Champions of Snow series

The issues plaguing Olympic venues mirror the struggles faced by our local snow sports industry. Here in New England, ski and snow businesses are already adapting to the impacts of climate change. During an average year, winter recreational snow and ice activities generate about $7.6 billion for the Northeast economy. But now, snow seasons in the Northeast are getting shorter and shorter, threatening the financial sustainability of ski resorts and other snow-based companies. By 2100, it is estimated that only 4 out of the 14 major ski areas in the Northeast will still be open. We saw a glimpse of that future in the 2009/2010 snow season, during which the Northeast ski mountain industry lost 1,700 jobs and $108 million in economic value.

In our Champions of Snow series last year, we spoke with five skiing businesses in the Northeast to learn about their actions to preserve the winter climate and economy. Mountains such as Mt. Abram are gearing up for uncertain winter snow seasons with 100% airless snow guns, which require no electrical energy for snow production. Berkshire East, the world’s only ski resort using 100% onsite renewable energy, has adopted solar and wind technology to reduce emissions and ensure energy security. Seasonal diversification is another means of ensuring economic security. By building infrastructure for summer activities such as mountain biking, zip lining, and hiking, ski mountains such as Berkshire East have transformed into year-round outdoor activity hubs.

This year, we’ve continued our Champions of Snow series with more local business interviews and will be releasing a video further investigating resilience efforts in the industry. Stay tuned for more updates on our endeavor!

AMANDA GRIFFITHS, EVENTS AND OFFICE COORDINATOR

Amanda comes to CABA from the Massachusetts State House, where she served as the Legislative and Communications Director and subsequently, as the Staff Director for the House Committee on Global Warming and Climate Change. While at the State House, Amanda focused on energy and environmental policy, including renewable energy adoption, transportation sector emissions, climate resiliency and toxics. She graduated from Colgate University in 2013 with a degree in Environmental Biology and Geography, researching climatology and ecosystem ecology in the Adirondacks and Costa Rica. Amanda is currently pursuing a Professional Certificate in Graphic Design at MassArt, where she hopes to build on her science and policy experience.