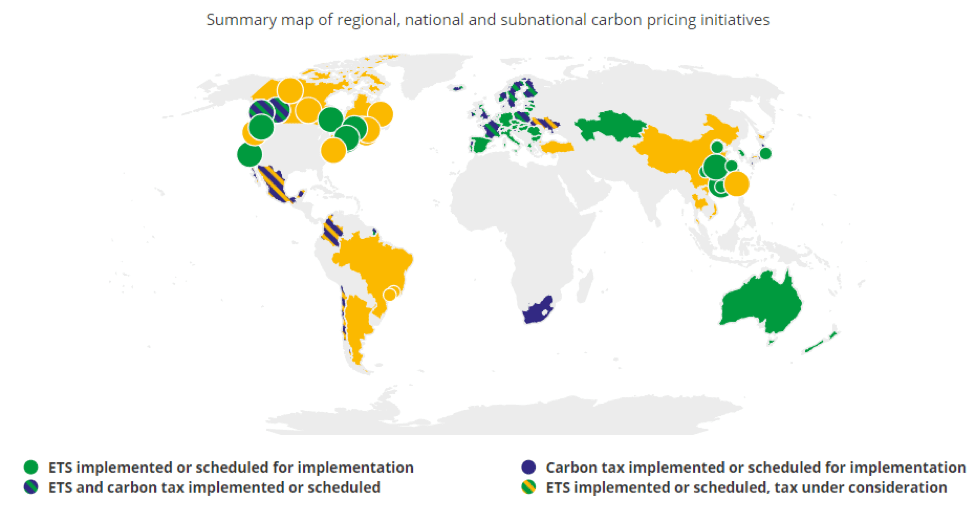

Putting a price on carbon emissions has been an effective, widely adopted approach to mitigating climate change. 47 carbon pricing mechanisms are currently in effect or scheduled for implementation around the globe, spanning 42 countries and covering 14.6% of global GHG emissions. To quote the World Bank, “developed countries must take the lead in committing to deep emissions cuts [and] pricing carbon.” So far, we’ve seen many nations step up to the plate.

Current Canadian Carbon Policy

Canada is one such country that has distinguished itself as a carbon pricing trailblazer. In the Vancouver Declaration of March 2016, Canada created an ambitious emissions reduction goal: a 30% reduction below 2005 levels by 2030. The December 2016 Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change established nationwide carbon pricing as a means of achieving this goal. Canada’s federal government has since been pushing for ubiquitous, federal carbon pricing standards to help the country achieve this benchmark.

Four of Canada’s ten provinces—British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec—already have carbon pricing systems. The other six—Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island—do not. By September 1st of this year, provinces without carbon pricing must submit a plan to the federal government detailing how they’ll meet the minimum emissions reduction goals laid out in the Pan-Canadian Framework.

Provinces with plans that are insufficient to meet Canada’s reduction goals will be forced to adopt a carbon pricing policy created by the federal government (referred to as the “federal backstop”). The federal backstop will price carbon at $20 per ton starting January 1st, 2019 and increase the price per ton by $10 each year, such that carbon emissions will cost $50 per ton in 2022. Provinces had the chance to voluntarily adopt the federal backstop by March 30th, but none did. In fact, some provinces have even threatened to sue the the Trudeau Administration over mandatory carbon pricing—more on that below.

The May 2018 ECCC Carbon Pricing Report

The Environmental Impact

A report recently released by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) entitled “Estimated Results of the Federal Carbon Pollution Pricing System” makes the quantitative case for carbon pricing across the Great White North. Between 2018 and 2022, if each Canadian province either continues with current carbon pricing mechanisms (for those that already price carbon) or adopts a carbon pricing equivalent to the federal backstop, the country will cut its carbon pollution by 80-90 million tons. Quoting the report, that’s a reduction comparable to taking all of Canada’s cars off the road or shutting down 20–23 coal-fired power plants for a year (Canada currently has 16 such plants).

Preventing 80-90 million tons of carbon emissions would constitute a 11.6% emissions reduction. That prediction is dramatically higher than those predicted by studies on potential carbon pricing schemes in the United States. In other words, the impact of carbon pricing—in Canada, in the United States, and elsewhere—is potentially much greater than policy experts have reported thus far.

The Economic Impact

Economically, the report determines that carbon pricing would have no significant impact on Canada’s rising GDP. The potential difference in GDP due to carbon pricing is estimated to be 0.1%, which is less than the typical impact fluctuating international energy prices have on the country’s economy. Historical data from Canada’s four provinces that have carbon pricing corroborates these conclusions. British Columbia has put a price on carbon since 2008, and between 2007 and 2015, its GDP grew 17% while gas demand dropped 15% per capita. These four provinces also experienced the most GDP growth in 2017.

It’s critical to note that provinces will have the autonomy to decide how revenue generated by carbon pricing is spent. For example, provinces could allocate more money to rapid transit, provide home renovation rebates for energy efficient remodeling, invest in the clean energy sector, subsidize rebates on green appliances, or even provide direct cash rebates to families. For example, the ECCC predicts that the average two adult, two child household would receive a $540 rebate as of 2018, which is more than the cost the family would pay on carbon fees. In British Columbia, carbon pricing revenue is currently used to both provide a 50% reduction in Medical Service Plan (province-provided health insurance) premiums and slash personal and small business corporate income taxes.

The ECCC’s latest report also omits certain potential economic benefits of carbon pricing. Paying for carbon emissions incentivizes businesses to adopt innovative clean energy solutions, spurring investment. Increasing investments will foster the growth of carbon neutral sectors, such as clean energy and public transportation. Carbon pricing is therefore a catalyst of innovation, investment, and long-term sectoral growth.

Furthermore, eliminating emissions also eliminates certain costs of emissions. Annual insured losses in Canada due to extreme weather have increased from $400 million in 1983 to $5 billion in 2016—a 1250% increase. Carbon pricing would mitigate the effects of climate change, thus reducing these costs. By 2020, the regular cost per annum of climate change in Canada is estimated to be $5 billion. By 2050, costs of climate change in Canada are predicted to rise to $21 – 43 billion per year.

The ECCC notes that none of the aforementioned economic impacts of carbon pricing were incorporated in their report as they are difficult to quantify and predict. But one thing is for certain: carbon pricing will contribute to environmentally and economically beneficial feedback loops. Such outcomes will not only be eco-friendly, but will also be economically friendly through savings and growth.

Compared to Other Emissions Reduction Policies

Of course, carbon pricing is not the only emissions reduction policy that Canada has worked to implement. Economy-wide “complementary measures” laid out in the 2016 Pan-Canadian Framework, such as clean fuel standards, methane regulations, and coal phase-outs, are important parts of the picture, too. However, as the following graphic shows, federal carbon pricing in Canada is forecasted to be substantially more effective at reducing pollution.

Political Hurdles

Despite the apparent benefits of carbon pricing, not every Canadian province is onboard with the federal government’s plan. Certain provinces are either reluctant to put a price on carbon or fully opposed to the proposal.

Manitoba, one of the six provinces without carbon pricing currently, is politically onboard with carbon pricing. The province currently plans to implement a carbon price in September of this year. Estimates project the province’s government will reap approximately $143 million in revenue over the following year. However, a carbon tax bill has not yet been introduced, and current plans set a fixed price of $25 per ton price on emissions, which will be insufficient once the federal rate surpasses that price.

Nova Scotia has proposed a cap-and-trade program, which will only require companies and utilities to track their emissions. That promise is supported by the fact that the province has already reached the national GHG emission reduction target of 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. Nova Scotia will notably have a cap-and-trade system that only operates within the province, unlike Ontario and Quebec’s cap and trade systems, which are linked with California. The Nova Scotian government has remarked that this will ensure emissions reductions occur within the province. As it stands, the province’s cap-and-trade program will almost certainly align with the Canadian federal government’s standards.

New Brunswick plans to use its preexisting gas tax as an equivalent to a price on carbon. However, there are doubts regarding the plan’s compliance with the demands of the Pan-Canadian Framework. It is possible that the province will be subject to the federal backstop, either fully or partially.

Scott Moe, Premier of Saskatchewan, is staunchly opposed to pricing carbon and has produced no suitable plans. The province has threatened to sue the Canadian federal government should the federal backstop be imposed on them. In its 2017 “made in Saskatchewan” climate change plan, titled Prairie Resilience, the province proposed emissions reductions via technological innovation. However, federal officials have warned the province that the plan is unlikely to meet federal standards. Saskatchewan is another province that may be required to adopt the federal backstop.

Similar to New Brunswick, the Newfoundland and Labrador government has suggested it will transform its existing gas tax into a carbon price. Details regarding the province’s plans were scheduled to be released this spring. Finally, Prince Edward Island has said it is working with the Canadian federal government on potential policy options. As of April, carbon pricing was not included in the province’s budget. Though the province’s collaboration with Ottawa is promising, the secrecy of its plans has raised concerns.

On a federal level, the country’s Conservative party has opposed Ottawa’s proposed federal backstop. The party claims it will present a plan to reduce national emissions in accordance with the 2016 Pan-Canadian Framework without using a federal carbon fee, but the details of that plan have yet to surface. Interestingly, Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Office has the newly-vested power to review the financial implications of a political party’s budget proposal. Having the PBO review both the Trudeau administration’s carbon pricing plan and that of the Conservative party (if it is ever presented) will permit the two proposals to be objectively compared.

A Reduced Carbon Canada

Carbon pricing is scheduled to make a nationwide debut in Canada starting in 2019. By September, however, the country’s province’s must submit their emissions reductions plans to the federal government for consideration. Those that do not meet federal standards will be compelled to implement the federal backstop, which charges $10 per ton of carbon in 2018 and increases by $10 annually until hitting $50 in 2022.

In its latest carbon pricing report, the ECCC makes a compelling case for carbon pricing to be implemented across the country. The implementation of such pricing is essential to Canada’s compliance with the 30% emissions reductions target defined in the Pan-Canadian Framework. Quantitative models suggest that carbon pricing will have a minimal impact on the country’s economic welfare as a whole. In fact, it’s likely carbon pricing will promote macroeconomic innovation, investment, and growth, while also providing savings and other benefits for Canadian households. Notably, provinces will be able to choose where they spend the money generated by carbon pricing. That money won’t just disappear—it will likely help fund the country’s transition towards a healthier, greener future.

As with any proposed fee, Canada’s carbon pricing plans are being hotly debated. Not all provinces are on the same page. Some already have carbon pricing; some plan on implementing carbon pricing or similar policies; some have been unclear or secretive about their plans; and one in outwardly opposed to accepting the federal backstop. However, given that carbon pricing is a trending and demonstrably beneficial policy solution, one would hope that Canada will soon “put a price on it.”