After an eight year hiatus, New Jersey is officially back in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). On June 17th, the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) adopted two rules prompting the state to rejoin the electric-sector cap-and-invest program. The move, made under the directive of Gov. Phil Murphy (D), was several years in the making.

What’s RGGI again?

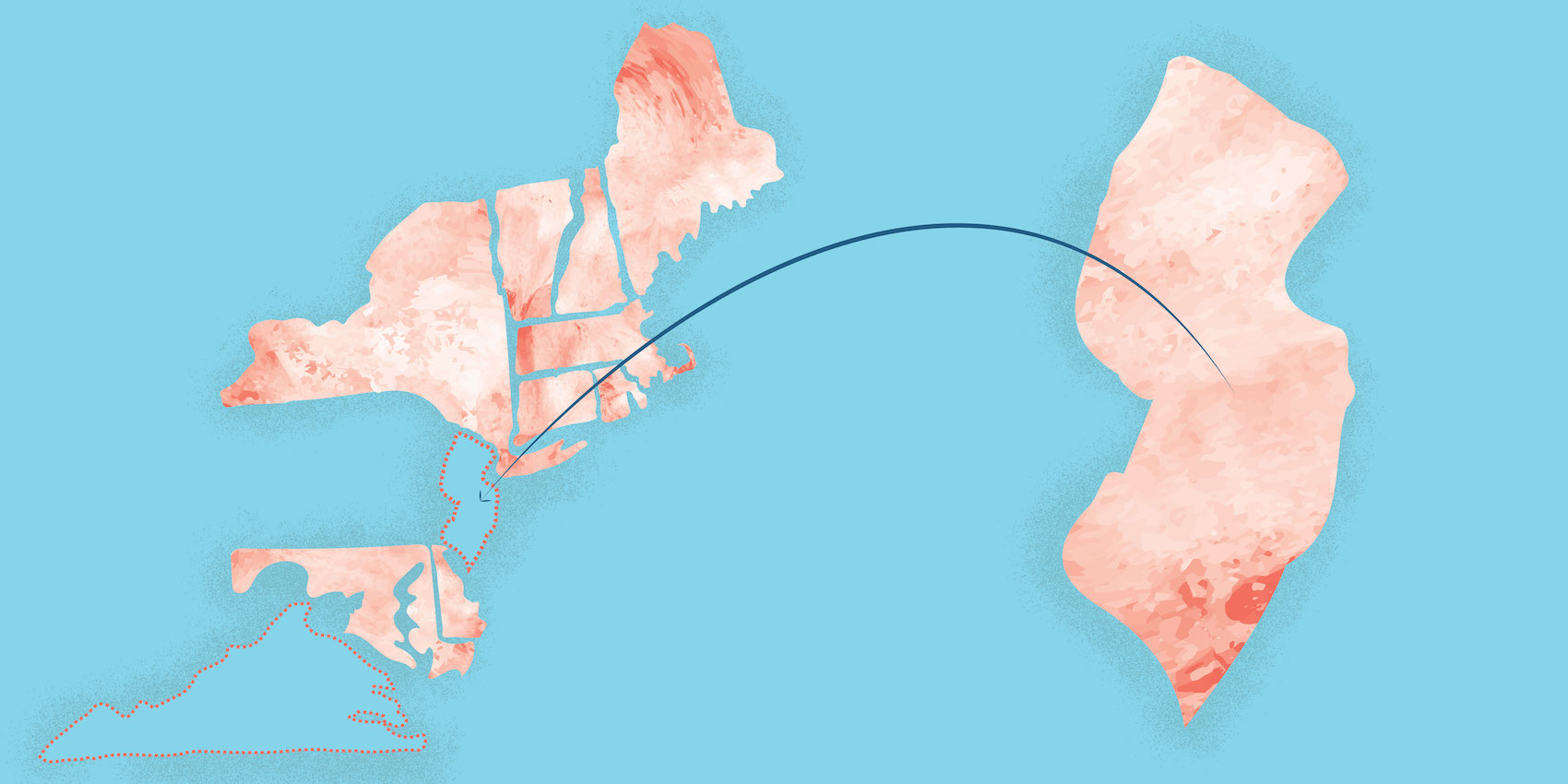

RGGI is a cap-and-invest program regulating electric-sector emissions in nine Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont).

These are some key elements of the regional carbon pricing program:

Declining cap

The program sets an annual cap on the region’s total carbon emissions from the electric sector, which declines each year by 2.5%. In 2019, the adjusted cap decreased to 58.29 million carbon tons.

Quarterly auctions

Power plants purchase allowances, or permits to pollute, in quarterly auctions. Regulated entities must purchase enough allowances to cover the emissions they generate in the program’s three-year compliance periods.

Investments

Revenue from allowances is invested in energy efficiency, GHG abatement, electricity bill assistance, and other causes that individual states deem worthwhile.

Price-control mechanisms

If allowance prices exceed predefined price levels, the Cost Containment Reserve (CCR) triggers the release of additional allowances. In 2021, the trigger price for additional allowances is $13, so if allowances are going for a higher price than that, more will be added to the bidding pool. On the flip side, if prices are less than established levels ($6 in 2021), the Emissions Containment Reserve (ECR) withholds a number of allowances, removing them from the pool. Since price uncertainty is an inherent challenge of cap-and-invest programs, these mechanisms ensure that prices are not too volatile.

Compliance periods

Compliance periods last three years, and companies can meet up to 3.3% of their compliance obligations through the purchase of offsets.

The program has played a crucial revenue-raising role in the states where it has been implemented, bringing in a total of more than $2.5 billion in auction revenue in its first eight years.

How did we get here?

In 2003, the governors of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont began discussions on developing a regional cap-and-invest program that would mitigate carbon emissions from power plants. Regulation began in 2009, and member states quickly began to reap the benefits of the emission-trading scheme. In just two years, RGGI auctions generated $118 million for New Jersey and helped reduce ratepayer costs by $149 million, according to a 2018 report by the Analysis Group.

But under Republican Gov. Chris Christie’s leadership (or lack thereof), New Jersey withdrew from RGGI in 2012. Christie described the program as “gimmicky” and “a failure”, and critics deemed the departure a careful move to appease conservatives in the state.

After all, the program was benefitting the state, both financially and environmentally, and Christie himself admitted that leaving it wouldn’t save ratepayers a significant amount of money. On the flip side, a 2015 Acadia Center report found that the state had already forgone an estimated $130 million in revenue, and could miss out on an additional $359 through 2020.

In the 2017 gubernatorial elections, Christie was term-limited and Phil Murphy (D) handily defeated his Republican opponent. Murphy campaigned on the promise of rejoining RGGI, and when he took office in January of 2018, he immediately issued an executive order to rejoin the emission trading system.

“The reckless decision to pull out of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in 2012 cost the state millions of dollars in revenue that could have been used to put toward initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve the health of our residents,” Gov. Murphy said in a statement.

What does it all mean?

New Jersey’s electric sector emissions cap for 2020 is 18 million carbon tons. That’s a lot higher of a cap than the 12.6 million ton limit most environmental groups advocated for, but it’s an emissions-limit and revenue-generator nonetheless. The cap will decline by 30% through 2030.

New Jersey wasn’t supposed to be the only new addition to RGGI this session. Virginia was also widely expected to join, but its majority-Republican legislature opposed the move. In May, Gov. Ralph Northam (D) signed a new state budget without vetoing the provision that barrs the state from joining the cap-and-invest program. That move infuriated environmental groups in the state, and Virginia’s much-anticipated entry will likely be delayed until 2021, assuming that next year’s budget doesn’t contain the same restriction.

While RGGI has effectively raised revenue and helped reduce emissions, as currently designed, the program does not go far enough in reducing emissions on its own, according to a 2018 Climate XChange report. As electric-sector emissions have gone down in the region, pollution from other sectors, like transportation, has risen. That’s why it’s imperative that all Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states pursue ambitious goals in their exploration of the Transportation and Climate Initiative (TCI), a proposed regional cap-and-invest program for transportation-sector emissions. While many RGGI states, including New Jersey, have indicated they will join TCI, some — namely Maine, New Hampshire, and New York — have yet to.

What else is up with carbon pricing in New Jersey?

While New Jersey’s re-entry into RGGI is undeniably a good thing, there’s lots more work to be done. On-the-ground advocates there have recognized that; Princeton University students, branded as the New Jersey Student Climate Advocates, have been actively working on developing a “carbon cashback” policy that would rebate revenue from a fee on carbon pollution back to households. That proposal has not yet been introduced in the legislature, but is another potential step in disincentivizing fossil fuel usage across all sectors of the New Jersey economy.

The group has been meeting with unions, environmental groups, businesses, municipalities, and other stakeholders across the state to develop a policy that would cut pollution from transportation and heating fuels, said Jonathan Lu, the group’s Co-Founder and Co-Director.

Revenue could be used to fund:

- Investment in alternatives to polluting forms of transportation, heating, and industry

- Climate resiliency initiatives

- A monthly rebate to protect households

- Tax relief for vulnerable businesses

The student group has grown tremendously in recent years, working directly with lawmakers, and expanding far beyond the confines of Princeton University, where it was born.

“We have really stepped up our game in terms of recruiting students,” Lu said. “We’re working with students all over the state.”

To learn more about the group or get involved with its “carbon cashback” efforts, follow it on Instagram (@NJclimateadvocates) or contact the students at nj.climate.policy@gmail.com.

“The policy is still under development and we would love to have further discussion with any interested stakeholders based in New Jersey,” Lu told Climate XChange in an interview.

While the students plow ahead with their carbon pricing initiative, they can rest assured that at least some tangible progress was made this session in regards to pricing carbon. Years removed from Gov. Christie’s ill-advised decision to pull New Jersey out of RGGI, the state will begin to once again reduce emissions and raise revenue for initiatives that will further help combat climate change.