As the global response to the climate crisis ramps up, carbon offsets have arisen as a central issue in policy decision-making at all levels. Offsets allow polluting entities to compensate for their carbon emissions by funding an equivalent amount of emission reductions in an external project. Examples of common offset projects include renewable energy projects, reforestation, methane capture from mines or agriculture, and so on. Offsets can significantly reduce the costs of compliance with emissions reduction targets, allowing reductions to come from the lowest cost sources first. In many cases, carbon offset projects also include a suite of co-benefits that support sustainable development in the project locations. That said, there are many controversies and uncertainties around carbon offsets, particularly as it relates to their environmental integrity and ethics.

Carbon offsets are currently under discussion at the international level, with the Article 6 market mechanisms of the Paris Agreement being the only area of negotiations not finalized at COP24—the latest UN climate conference in Katowice, Poland. The global community is looking to reach an agreement on these issues by the end of this year at COP25 in Santiago, Chile. Meanwhile, at the local level, offsets have faced criticism from groups arguing that they let polluters off the hook for their emissions, and that emission reductions should be benefiting the communities that have been negatively affected by the polluting industries at the source of those emissions, instead of being offset in places often far away.

There are thus a variety of questions that need to be understood around offsets and their role in combating carbon emissions. What needs to be done in the Article 6 negotiations at the international level to ensure environmental integrity and environmental justice? How do the dynamics of local, domestic, and international offsets differ, and where do they intersect? How are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) being mainstreamed into offset projects and to what effect? What is the gold standard for offset projects going into the future?

While it will not answer all these questions, this article lays the groundwork of the existing carbon offsets landscape, in preparation for a fuller research report to come.

Recommendations for Article 6 Negotiations

Negotiations around Articles 6.2 and 6.4 are particularly prevalent in current international discussions, and are critical because poor design could lead to higher emissions and weaker ambition.

Read More

Article 6.2

Article 6.2 covers bilateral agreements between countries in which internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs) are exchanged. Essentially, if one country is able to reduce emissions beyond the amount it promised in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement, another country can purchase these additional reductions to count towards its own NDC.

A major risk is the possibility of trading “hot air” if a country’s NDC is too weak and it is easy to overachieve on it without actually taking substantial climate action. Safeguards therefore need to be adopted, including transfer limits, maximum limits on use of ITMOs towards NDCs, carry-over of ITMOs from one NDC period to the next, and proper tracking. Some ITMOs should also be cancelled in a transaction to ensure overall mitigation, with neither Party claiming emission reductions. As a simple example, one country could purchase 100 offset credits representing 100 tons of carbon dioxide that were reduced in another country, but only be allowed to register 85 tons of emissions reductions towards its NDC, with the remaining 15 credits cancelled administratively. With no nation claiming these emissions reductions, there is overall mitigation globally. This prevents against zero-sum offsetting where there is neither an increase nor a reduction in emissions.

Article 6.4

Article 6.4 covers a mechanism for mitigation and sustainable development that essentially replaces the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) under the Kyoto Protocol. There were serious flaws in the CDM that need to be addressed in this next iteration.

The premise of the CDM was that a country with an emissions reduction mandate could implement an offset project in a developing country, giving it flexibility in meeting emissions goals, while simultaneously spurring development. In practice, however, the program has been criticized for violating the principle of additionality—the idea that projects represent new emissions reductions that would not have occurred without the offset funding. There are estimates that as many as 85% of CDM projects would have occurred regardless of the CDM revenues. This clearly diminishes the environmental integrity of the mechanism, with additional criticisms that CDM projects have not contributed adequately to SDGs in host countries. One study suggested that “less than 1% [of CDM projects] are likely to contribute significantly to sustainable development in the host country.”

It is not advisable to simply transfer existing projects and credits under the CDM to the new Article 6.4 mechanism. Beyond the flaws with the CDM itself, there are questions around baseline setting for determining the crediting of offset projects. NDCs have to be considered when formulating the baseline used in offset calculations to ensure that only efforts that go beyond the current level of ambition are credited. This could be done in a variety of ways, including only allowing offsets to be used toward the conditional portions of NDCs.

Mechanisms to prevent against double counting are also crucial. The country selling emissions reduction credits and the one purchasing them should not both be able to count them towards their NDCs. There must be adjustments to account for this in ITMO transfers, due to the huge importance of tracking and transparency in the final market design.

As discussed under ITMO transfers in Article 6.2, one valuable approach to ensure environmental integrity in a carbon market is to adopt partial cancellation of credits when they are transferred, so that neither Party claims the emissions reduction and there is an overall mitigation in global emissions. This could be contentious at upcoming COP25 negotiations in Chile, as Brazil is resisting attempts to prevent double counting, calling “for all existing credits from the CDM to be carried forward beyond 2020.” Many existing CDM projects are located in Brazil, so this would benefit their revenue stream, but would lead to surplus emissions on the market and effectively lower ambitions.

Some restrictions are needed in the transition of existing CDM projects to the new system. Otherwise, there will be a vast oversupply of emissions reduction credits in the market, lowering the price, environmental integrity, and credibility of the mechanism. Possible criteria to restrict the transition are: the date of the project, the type of project, and allowable host country locations. There could also be restrictions regarding eligibility of projects in sectors outside of NDC scope—which could create perverse incentives to narrow the scope of NDCs to allow for more projects—or whether to accept activities that are part of the unconditional portion of the NDC. The application of standardized methodologies or new additionality tests are other possible quality assurance mechanisms.

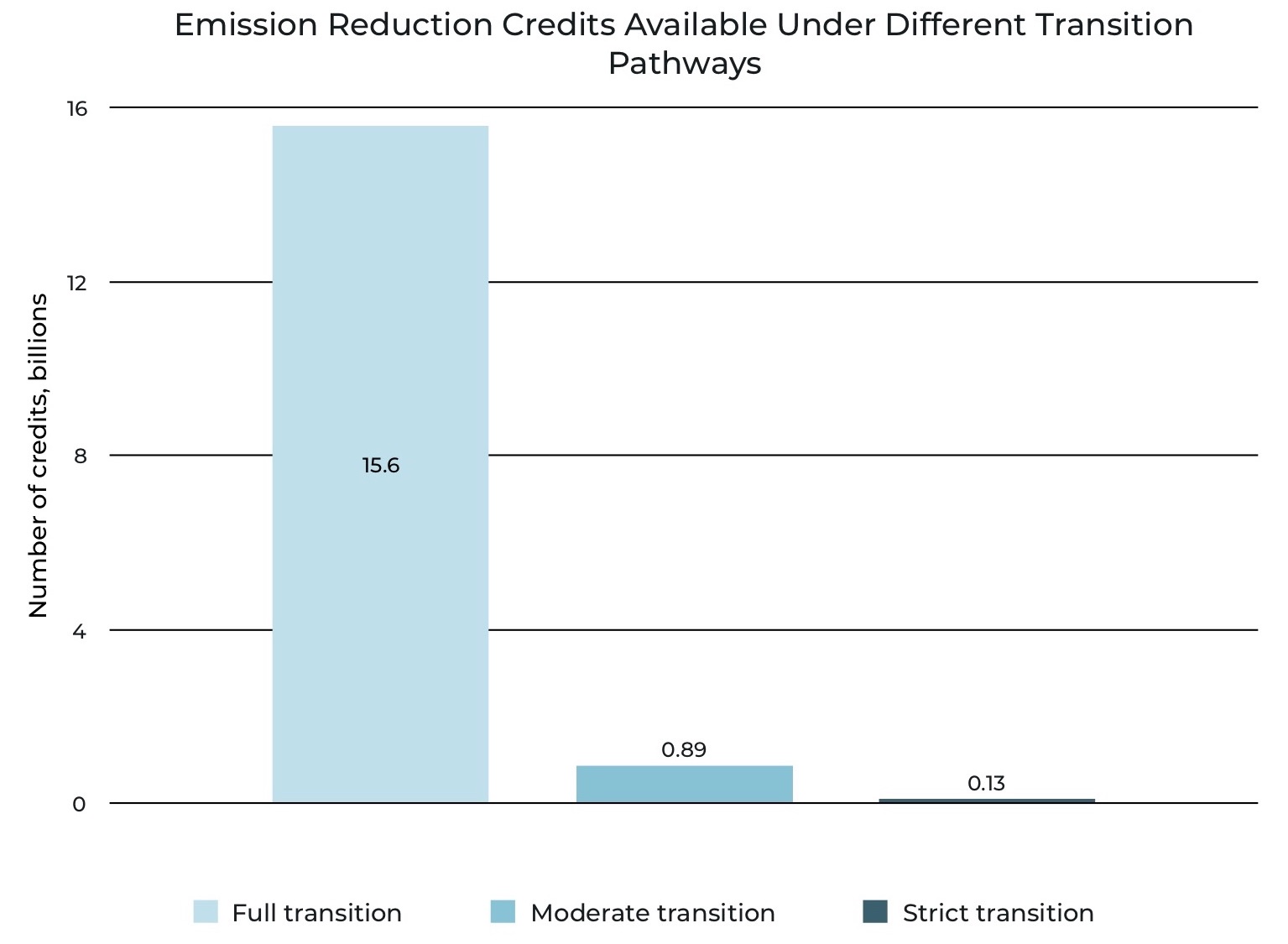

One study found that a full transition of CDM projects would lead to a volume of 15.6 billion credits until 2030, while a moderately restricted transition (2013 registration cut-off date, exclusion of industrial gas and large hydro projects) would limit that to 0.89 billion, and a strict transition (November 2016 registration cut-off, same project exclusions, host countries limited to Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States) would further reduce credit volume to 0.13 billion.

While it is necessary to prevent too many credits from flooding the market, some level of CDM transition is desirable to preserve knowledge of methodologies and provide confidence for existing and long-term investments. There is likely to be higher private sector participation with a more complete transition, as there would be a broader scope of eligible activities, likely a more lenient baseline, and lower transaction costs.

While it is necessary to prevent too many credits from flooding the market, some level of CDM transition is desirable to preserve knowledge of methodologies and provide confidence for existing and long-term investments. There is likely to be higher private sector participation with a more complete transition, as there would be a broader scope of eligible activities, likely a more lenient baseline, and lower transaction costs.

Dynamics of Domestic vs. International Offsets

It is not just the international community that is looking at offsets. Carbon offsets are a feature of many domestic policies, including cap and trade systems in the U.S., such as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and California’s Western Climate Initiative. The treatment of offsets differs at the domestic versus international level though, and is worth considering if a global, compliance-approved carbon market will be entering into force in the near future.

Read More

Differing Incentives

One challenge with establishing an international offset system is the different incentives such a mechanism provides for countries that are buying offsets versus those selling them. For countries that are buying offsets, using an international market lowers the cost of achieving their NDCs and could therefore enable them to take on more ambitious targets. However, for the countries selling offset projects, an international carbon market creates the perverse incentive to narrow the scope or limit the ambition of their NDCs, so that more of their projects are eligible to sell and earn revenue rather than be used for their own domestic targets. This suggests the importance of economy-wide NDC targets that do not exclude certain sectors, and of course, of high-ambition targets.

Domestic Offsets for NDC Achievement

Unlike under the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement includes emissions reduction targets for developing countries, which are expected to increase in ambition over time. Developing countries therefore cannot sell all their offsets, as they will need at least some of them to achieve their own domestic targets. This leads to program design questions around transfer limits.

Even in the case of using domestic offsets to meet NDCs, if offset projects are in covered sectors of the NDC, it can be challenging to show additionality. There is thus discussion of making offsets only count for the conditional NDC targets, not the unconditional targets that should be met anyway without offset revenue.

Environmental Justice

There are environmental justice (EJ) arguments in favor of domestic over international offsetting. Using California as a domestic example, a portion of offsets in their emissions trading scheme must benefit the state environment and economy directly. This was pushed for by EJ groups who argued that polluters should reduce their emissions locally and provide co-benefits, such as cleaner air, to local communities.

While this argument makes sense at the local level, scaling up, international offset projects that also contribute to SDGs could be argued to be contributing to EJ goals. Generally, the countries with the highest emissions and contributions to the climate crisis are the ones now buying most offsets. Therefore, funding offset projects that simultaneously spur development in countries that have been historically less responsible for climate change can facilitate an equitable transition to a low-carbon global economy.

Public Opinion

There are varying levels of public acceptance for domestic offsets compared to international offsets. General acceptance of these programs is important for establishing trust and giving investors confidence in the longevity of the programs. Several studies have demonstrated that different framings of the concept of offsets were able to shift public opinion more in the direction of one or the other. For example, using an economic efficiency argument was most successful in increasing support for international offsets. Conversely, framing the idea around local co-benefits to the domestic economy and environment led individuals to prefer the idea of domestic offsetting, even if it was slightly less economically efficient.

Acceptance of offsets at all, location aside, decreased in response to arguments concerning their effectiveness and ethics. Concerns over breaches in the additionality principle in the Clean Development Mechanism reduced the credibility and public acceptance of an international offset system, leading the public to favor local projects.

SDGs and Carbon Offsets

In 2015, the United Nations published 17 Sustainable Development Goals to achieve for 2030. There has been a great deal of attention at promoting SDGs in carbon offset projects.

Read More

Value of Integration of SDGs

Sustainable development goals are increasingly becoming explicitly incorporated into offset projects, instead of simply being considered co-benefits. The Gold Standard organization reports that, “for each ton of carbon avoided, its projects deliver up to $177 of additional value towards the Sustainable Development Goals.” Certifying the SDG contributions of offset projects offers consistency and comparability beyond the current co-benefits system. Putting an actual value on the non-carbon reduction benefits can also attract more investment to projects with these broader societal benefits.

Performance of Specific Project Types

Many types of offset projects can include SDG benefits. Two common examples are improved cook stoves and water filtration systems.

Cook Stoves

Improved cook stoves are a frequently cited offset project for SDG benefits. Burning solid fuels, such as charcoal or wood, is inefficient, emits a great deal of carbon dioxide, and produces air pollution and negative health impacts. As it is typically women who must collect and prepare these fuels, the opportunity cost of fuel collection also negatively impacts gender and economic equality, as well as education. Cook stove projects can thus contribute to SDGs 7 (affordable and clean energy for all), 13 (climate action), 15 (life on land), 1 (no poverty), 8 (decent work and economic growth) and 3 (good health and well-being).

In practice, some cook stove projects contribute more to these goals than others. For example, one study found that improved biomass cook stoves do not significantly reduce fine particulate matter, which is the major health concern with conventional cook stoves. Instead, it suggested liquefied petroleum gas stoves led to greater reductions in Disability Adjusted Life Years.

Water Filtration

Water filtration is another common project that contributes to SDGs. The idea is that water filters can reduce carbon emissions because they eliminate the need for boiling water to sterilize it. Reducing the need to boil water every day saves fuel from being burned, oftentimes carbon-intensive fuels like charcoal. These projects clearly also contribute to SDG 3 (good health and well-being).

A case study of a water filter distribution project in Kenya revealed the importance of independent monitoring of GHG reduction projects. The program that distributed the water filters had an internal monitoring system and reported a water filter usage rate of 81%, while an independent assessment found actual usage rates of 19% of households given filters. Additionally, not every household boiled the water before use to begin with, so there were also uncertainties over actual carbon emission reductions from the project. Accurate baseline determination and third-party verification are therefore key for environmental integrity.

It is clear that there are many complexities to the design and implementation of carbon offset programs, that will be at the forefront of the international community’s minds going into COP25, as well as domestically in RGGI and California.

Sign up to our newsletter here to receive updates on our full analysis on carbon offsets.