Our State Climate Policy Network Director, Noa Dalzell, is at the 26th Conference of Parties (COP26) in Glasgow, following the international climate negotiations, as well as robust state-level conversations centered around equitable climate policy. We’ll be sharing original, on the ground coverage from Noa as the conference progresses.

If you’ve been following COP26, you’ve likely heard about the logistical nightmare that the international climate negotiations have become — hours of lines to get into the venue, a scarcity of seating options, the list goes on. Climate advocate and founder of the U.S. Youth Climate Strike, Alexandria Villaseñor, lays out the situation quite well in this Twitter thread, so I won’t dive into too much detail. But, it’s been hectic to say the least.

By now, you’ve probably heard about the lines, access and representation issues at #COP26. But it’s been a really awkward, strange day, so I want to lay everything out here, because if you’ve wondered if #COP26 is okay, I’m gonna show you that no, #COP26 is really not okay/1

— Alexandria Villaseñor is at COP26! (@AlexandriaV2005) November 3, 2021

One of the most notable logistical phenomenons I’ve observed, however, are the dining options. There was plenty of talk around what kinds of food would be served at the venue, given how harmful large-scale animal agriculture is for the environment and how much more carbon-intensive meat and dairy is than plant-based food. So, leading up to the conference, I was excited to see headlines like this one declaring that “delegates will be served entirely plant-based menus.” Since then, however, I have observed first-hand that this is far from the case.

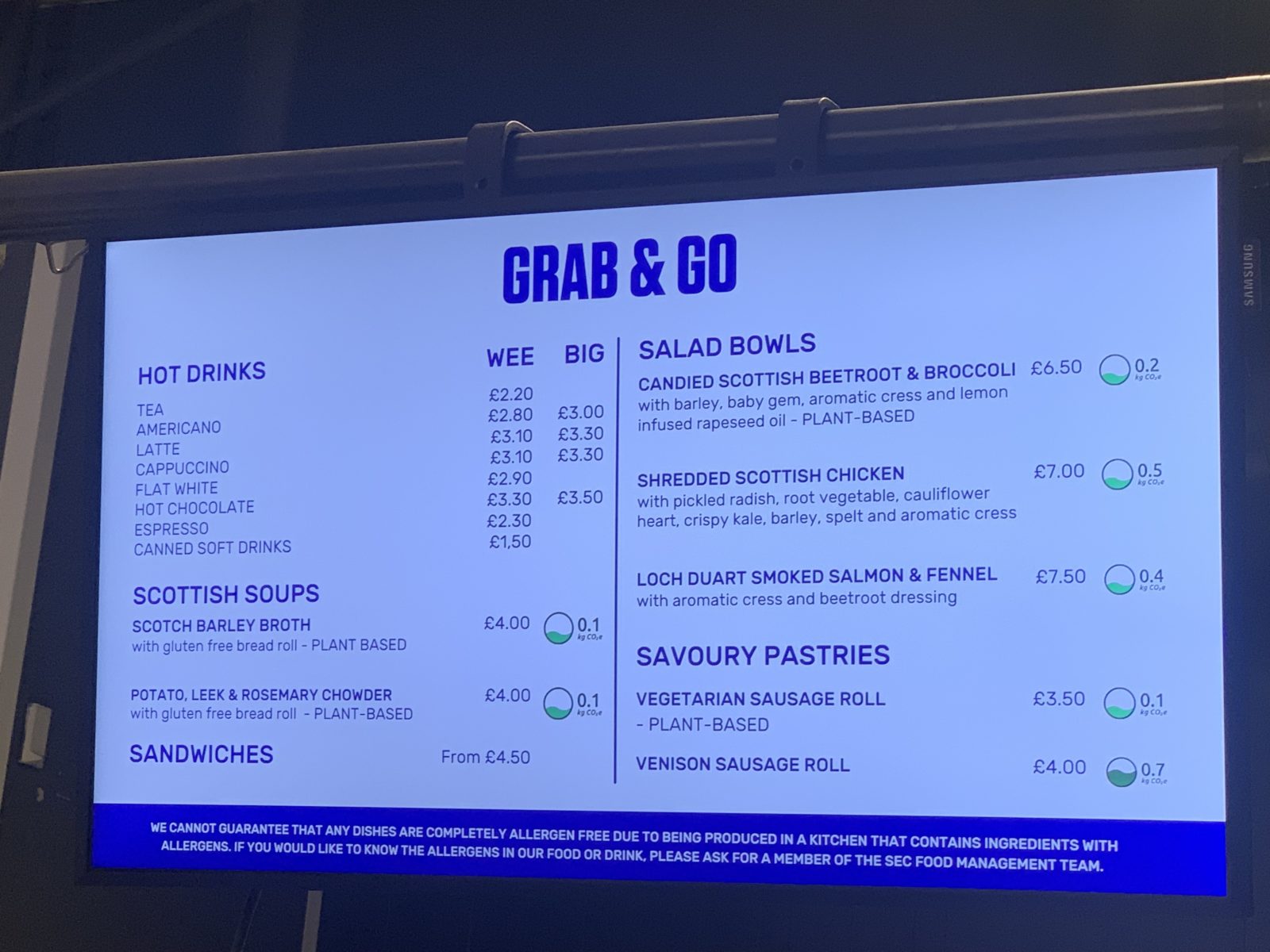

To be fair, most food venues do have at least one plant-based option, a welcome change from previous COPs. They also list the carbon footprint of different food items so that delegates can consider the environmental impacts of their food choices. Needless to say, the plant based options consistently score lower carbon footprints than their meat alternatives.

The food situation is striking, but hasn’t been too much of an inconvenience; to save money, I’ve been packing apples, granola bars, and delicious Scottish oatcakes into my purse ahead of each day. But the prevalence of mayo-chicken sandwiches and haggis (a *very* carbon-intensive Scottish meat pudding) is emblematic of a larger trend: the climate community has failed to embrace plant-based eating as a climate mitigation strategy.

The United Nations climate negotiations have largely overlooked the detrimental climate impacts of industrial animal agriculture. Under the Paris Agreement, countries were not required to set meat-reduction targets — the concept was laughable to a couple negotiators I spoke to. Perhaps even more striking, the Global Methane Pledge that was announced by 100+ countries last week failed to even mention animal agriculture, despite the fact that livestock emissions account for roughly 32 percent of human-caused methane emissions.

Why Has Animal Agriculture Been So Overlooked in International Climate Conversations?

The question has been on my mind all week. At a November 5th press conference held by the international anti-factory farming nonprofit Compassion in World Farming (CIWF), the group announced a new report, Breaking the Taboo: Why Diets Must Change to Tackle Climate Emergency.

Peter Stevenson, the lead author of the report, put it bluntly: “Without a dramatic reduction in meat and dairy consumption, we will not be able to avert global climate catastrophe.”

At the press conference, I asked Stevenson why he thought calling out the meat and dairy industries was taboo, even in environmental circles. After all, I had spent all week watching climate scientists and advocates alike enjoying meat-intensive meals. He explained how so many powerful industries and corporations are dependent on factory farming, such as the agribusiness companies that produce antibiotics, the breeding companies that raise fast-growing livestock, the cage and crate manufacturers, the grain sellers, and the export companies.

“All of their business models are utterly dependent on factory farming,” Stevenson said. “If we halved meat and dairy consumption, all of their sales would be halved.”

Can This Change?

In 2019, a special IPCC report on climate change and land described plant-based diets as a critical opportunity to mitigate climate change, and recommended a reduction in meat consumption to meaningfully curb planet-warming emissions. In 2020, an analysis by Greenpeace found that meat consumption in the European Union should drop by 71 percent by 2030, and by 81 percent by 2050.

“It is a myth that we need to produce 70 percent more food to feed a growing population,” Stevenson said. “We don’t. We need to halve meat and dairy production.”

A study by the U.N. Environmental Programme found that if the food fed to animals was instead fed directly to people, we could feed an additional 3.5 billion people each year. But at COP26, most of the conversations have been about reducing the emissions of industrial animal agriculture, rather than moving away from it altogether.

“The livestock sector has stated we can high-tech our way out of this,” Stevenson said. “A study by the EU Joint Research found that technological measures could reduce livestock emissions by 15-19 percent, but emissions from EU livestock need to be reduced by 75 percent to meet the EU’s net-zero target. Technological emission-reduction targets are, on their own, not enough — our consumption patterns also have to change.”

What Should Governments Do?

According to the CIWF report, governments need to make five important policy decisions in order to incentivize a transition to plant-based eating and put 1.5 degrees of warming within reach.

These include:

- Setting legally-binding meat reduction targets to ensure that overall meat consumption declines.

- Changing public procurement policies to ensure that the food served in schools, hospitals, and other venues contribute to lowering emissions.

- Running public information campaigns to inform people of the environmental implications of different dietary systems.

- Ending factory farming subsidies and repurposing them to reduce the cost of plant-based alternatives.

- Taxing factory farmed meat, and using the revenue to subsidize climate-friendly food, so that the overall price of food declines.

At a November 4th press conference titled “Addressing the Cow in the Room,” ProVeg International, the Humane Society International, and the Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation called on countries to act immediately.

Jasmijn de Boo, Vice President of ProVeg International, said that based on leading research, in order to achieve Europe’s stated climate goals, by 2040:

- Meat consumption must be reduced by 79 percent.

- Milk and dairy consumption must be reduced by between 74 percent and 83 percent.

- Egg consumption must be reduced by 83 percent.

- Seafood consumption must be reduced by 65 percent.

These goals will require significant systemic change — but systemic change is the cornerstone of the just transition. A good (and incredibly easy!) first step, however, is simply serving exclusively plant-based food at future COPs.

“Can you imagine going to a cancer conference and giving cigarettes at the door?” said Bernat Añaños, the co-founder of Heura Foods. “We are at a climate conference! We are selling food that has six times the carbon footprint of the plant-based option, and we still put it there! Why do we do that?”