Authors

Molly Freed and Wendy Jaglom-Kurtz, RMI

Rachel Patterson and Medhini Kumar, Evergreen Collaborative

Ruby Wincele and Paola Ferreira Miani, Climate XChange

Note: This article was edited on May 30, 2024 with updated figures for the number of measures included in states’ Priority Climate Action Plans.

View our spreadsheet containing key data and information from the 47 Priority Climate Action Plans submitted to the EPA as part of the Climate Pollution Reduction Grants program.

Almost every state has stood up to take action on the latest IRA opportunity. Here are the numbers documenting their climate ambition.

Millions of dollars are about to flow to states to help them tackle their unique local climate challenges. The Climate Pollution Reduction Grants (CPRG) program is one of the largest buckets of direct funding within the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), providing $5 billion to states, municipalities, Tribes, and other governments to reduce climate pollution. The first phase of the program, the planning grants, put $250 million in state and local governments’ hands to conceive of their clean energy future. And nearly every US state, along with D.C. and Puerto Rico, put their hand up for this tremendous opportunity by submitting a Priority Climate Action Plan (Climate Plan) to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) just last month.

It is a signal that a vast majority of US states — even ones that haven’t historically been leaders on climate — are eager to capitalize on the opportunity to address climate, advance clean energy, lower energy costs, clean up air pollution, and create jobs. States that might not have had the funding to invest in sectoral or economy-wide programs designed to reduce climate pollution now can — on their own terms, with nearly unlimited creativity.

This repository of action plans is our first opportunity to see how states are collectively approaching and tackling the climate crisis, with a huge amount of new information about each state’s approach to reducing climate pollution.

And a lot of money is on the table to bring these plans into reality. Following up this planning phase, EPA will soon unlock a whopping $4.6 billion in grants that states, Tribes, and other governments can use to implement actions in their Climate Plans. This means the strategies laid out in the state Climate Plans will drive a major national investment to cut climate pollution.

So, what do states want to do with this massive sum of funds? How ambitious are their plans, and what does this tell us about our nationwide climate progress?

Together, RMI, Climate XChange, and Evergreen Collaborative read a total of 6,795 pages of plans to answer these questions. This is a first look at what can be uncovered, with much more to come. For a complete look at our review, see our spreadsheet here.

By the Numbers — Initial Climate Plan Takeaways

Note: The data included below is a result of our collective first-pass review. As such, there may be minor adjustments made as we continue to dig into the detailed plans.

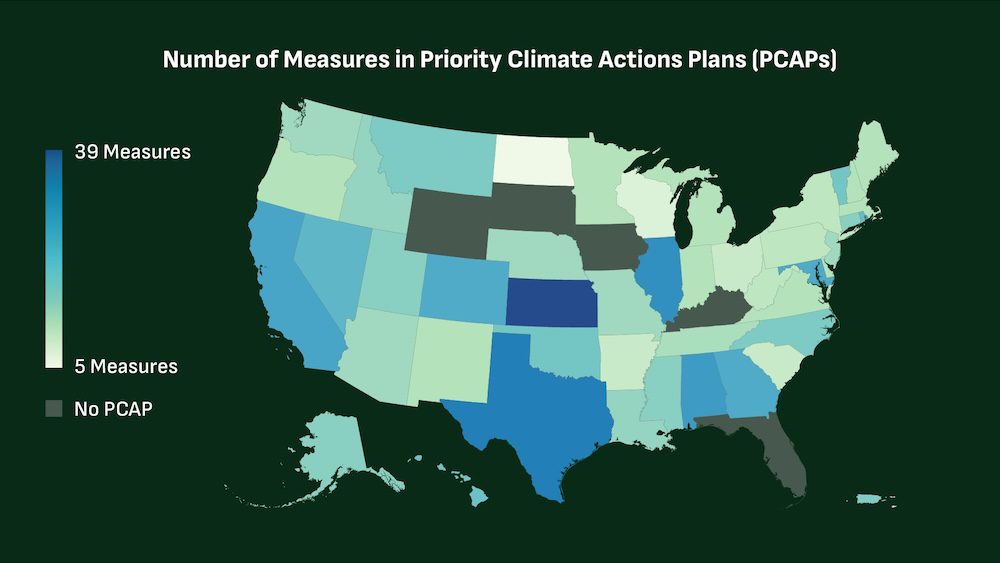

RMI, Evergreen, and Climate XChange reviewed 47 Climate Plans from 45 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia. The states and territories represented collectively account for about 90 percent of the country’s population and carbon pollution. For almost half of the states — 23 — these Climate Plans represent the first meaningful climate action planning effort since at least 2018, giving a very first view into how they might think about and approach climate action.

Whether a state chose to call its plan a “Priority Resiliency Plan,” “Plan for Environmental Improvement,” “Priority Energy Plan,” or simply “Priority Plan,” it used the opportunity to produce a clear list of measures to reduce climate pollution. These initial plans give advocates critical information to push for continued ambition and effective implementation with IRA funds to support.

Tackling Key Pollution Sources

The most critical component of the Climate Plan is the “priority measures” section that describes which activities, policies, and programs the state will pursue to cut pollution. States have started to articulate and focus their efforts, but we found significant variation in the number of measures and sectors addressed. These measures, or strategies, help us understand how states are planning to address climate pollution. They identify which sectors states are focused on, and whether that correlates with the most polluting sectors within that state or nationwide. The Climate Plans collectively included 654 priority measures to tackle climate change from geographies and political contexts across the spectrum. The plans ranged from 4 priority measures (North Dakota) to 39 (Kansas), with an average of 14 measures per plan.

Of course, it’s not just about the numbers: Some states chose to disaggregate several action items under one single “measure,” while others listed each specific action item as its own measure. For example, Alabama (24 total measures) listed the specific “Establishment of Solar/Charging Infrastructure Supporting Irrigation in Rural Alabama” as one measure, while D.C. (6 total measures) listed several strategies below their third measure, “Accelerate the deployment of local, clean, renewable, and resilient energy.”

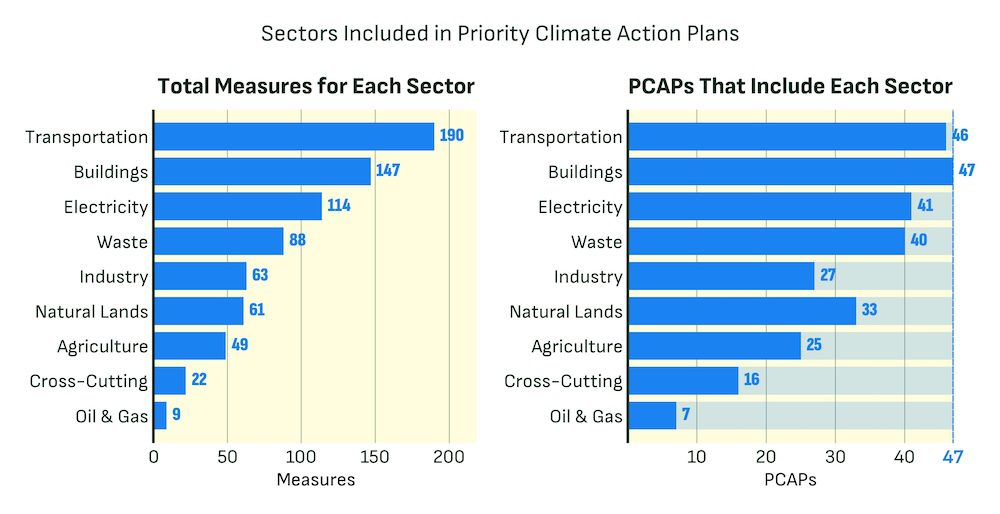

The transportation sector — the biggest source of US climate pollution and one with significant opportunity for reductions — had the most measures at 190 across 46 plans (all but two, Colorado and North Dakota). Every single Climate Plan included at least one measure related to the building sector (147 total measures), which is another significant emitter where states-driven solutions are the key to unlocking near-term progress. The third and fourth most addressed sectors were electricity (114 measures in total, included in 41 plans), another giant source of climate pollution, followed by waste (88 measures in 40 plans) where controlling methane can pick up big climate gains fast. This shows us that states are correctly focusing on many of the biggest problems.

But there are gaps too. Industrial measures were underrepresented in the plans (63 measures in 27 plans) despite the sector representing a larger proportion of US climate pollution than buildings and significantly more than waste. As states build on their priority plans and develop their Comprehensive Climate Action Plans due to EPA by roughly summer 2025, it will be important to emphasize that this sector is really not so “hard-to-abate,” with many options on the table for states looking to act.

Importantly, including a greater range of sectors in a plan does not necessarily mean greater pollution reduction or higher ambition. Some states chose to narrowly focus their Climate Plan on a couple of specific sectors that they hope to use the CPRG Implementation Grant funding to address, while leveraging other federal and state resources to address remaining sectors. Other states used the Climate Plan to address gaps or scale up their existing approaches and programs, especially for their highest emitting sectors. And still other states used their Climate Plans as a first step in identifying what action is needed — these plans tend to cover more sectors but may have lower ambition for each measure.

Leveraging Big Investments for Big Community Benefits

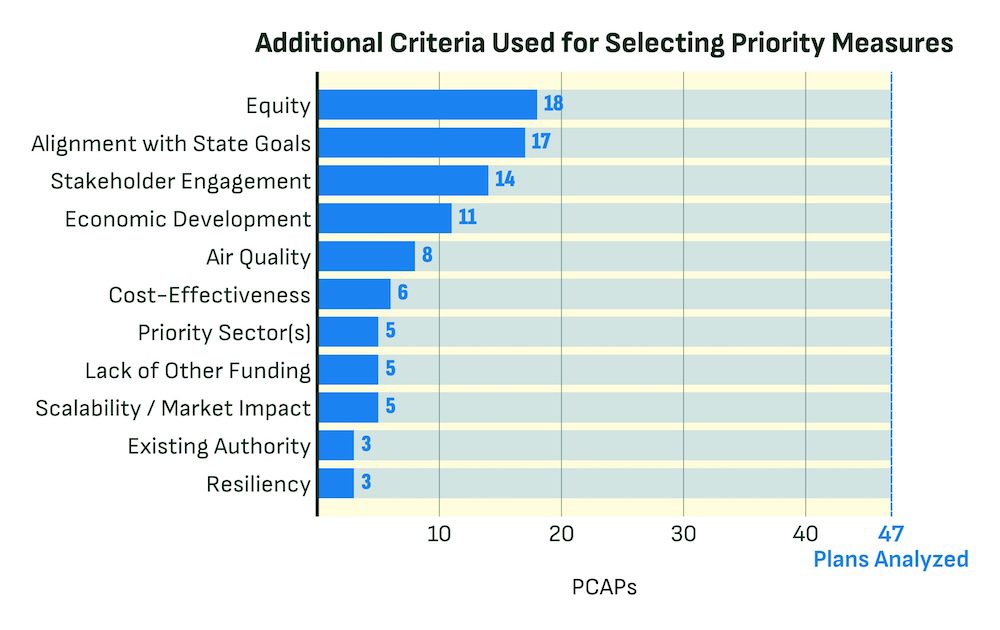

States are eager to create jobs, support communities, and grow their economies as they take climate action. EPA recommended focusing the Climate Plans on “near-term, high-priority, implementation-ready measures to reduce GHG pollution” — and states did so, while also including a more holistic focus on maximizing co-benefits. We saw that many states were interested in climate strategies that supported economic and health benefits, in addition to tackling greenhouse gas pollution, especially in states where that might make their strategies more politically palatable.

And states are finding ways to use the new federal funds to fill the gaps to reach these benefits. Interestingly, while some states chose measures that had an abundance of additional funding options (logged as “cost-effective” in the below chart), others specifically chose to include measures that couldn’t be funded through other avenues and for which CPRG funds were the best option. This shows that flexible funding streams can be used to complement other programs and incentives by layering or stacking multiple incentives to unlock greater benefits or by filling in coverage gaps left by other programs.

Combining Funding Mechanisms

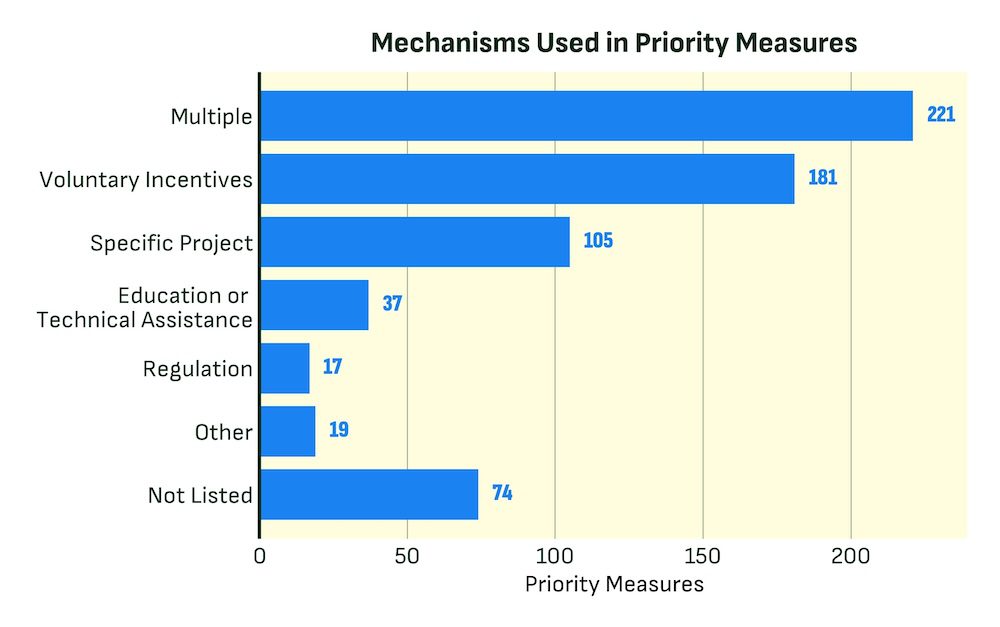

Combining IRA funds with clear standards provides an untapped opportunity. For the most part, states focused their Climate Plans on voluntary programs and specific projects even though standards can provide important certainty, toward both goal achievement and key industries and markets. Meanwhile, very few states included regulatory measures in their Climate Plans. This could be because they were inspired by the opportunity to use federal funds for “carrots” (usually much more politically popular than “sticks”), due to a lack of regulatory authority from the authoring agency, or because many states interpreted EPA’s “implementation-ready” guidance as “shovel-ready projects.” Where states used their measures to address high-level objectives (e.g., Ohio’s third measure, “Transportation Efficiencies”), they listed a combination of mechanisms to accomplish their desired outcome, listed as “multiple” in the chart below. Critically, 11 percent of the proposed measures across state plans do not clearly and actionably explain the activity, plan, or program, highlighting a need for additional work to make the measure a reality.

Going Above and Beyond

Many states are working to ensure their Climate Plans broadly benefit communities and leverage all available funds, but there is more to do. Per EPA guidance, the Climate Plans had to include four required “elements” or components: a GHG inventory, quantified measures, an analysis of benefits to low-income and disadvantaged communities (LIDACs), and a review of the state’s authority to implement the included measures. The majority of plans (45) included all four elements, while two states were missing one or more. States will be required to address these discrepancies in their follow-up Comprehensive Climate Action Plan.

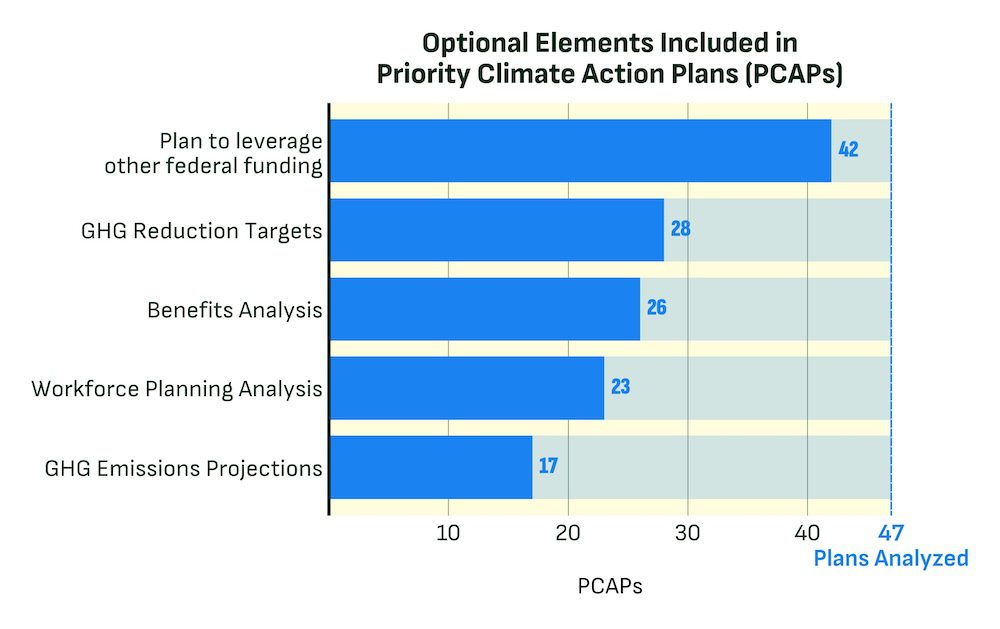

The Climate Plans could also include five optional elements: GHG pollution projections, GHG reduction targets, an overarching benefits analysis, a plan to leverage additional federal funding, and a workforce planning analysis. Forty-two plans included one or more of the optional elements, while five plans didn’t include any. These optional elements give us a better look into how realistic the plans are, as well as how states plan to operationalize their strategies in ways that will create jobs and community benefits. Most states included a plan to leverage additional federal funding (42 in total), while about half of states included each of the other elements. All states will be required to include these optional elements in the Comprehensive Climate Action Plans in 2025.

States are also engaging a wide range of key stakeholders to inform these plans, bringing communities, industry, and others along in their thinking. To prepare their Climate Plans, states were required to engage in stakeholder outreach. Early analysis reveals that state Climate Plan engagement reached nearly 16,000 stakeholders and collected roughly the same number of formal comments and suggestions. Our team will be taking a closer look at the depth and breadth of this outreach in future publications.

Big Opportunities Ahead

For the first time ever, states across the country are writing down their plans for meaningful climate action at the same time. We are looking forward to partnering with states, advocates, industry, labor leaders, and communities to strengthen, implement, and expand these Climate Plans, supported by billions of dollars of federal investment. Our first look shows big opportunities ahead, and there’s more to explore.

We are just starting our analysis to ensure states and advocates have the information they need to answer key questions, like:

- Which Climate Plans rise to the top and why?

- Which Climate Plans do a particularly good job of addressing key community needs, including workforce development, environmental justice, and stakeholder engagement?

- What measures stand out as particularly new or innovative?

- What measures might merit scaling across states?

- Which states’ measures are particularly well targeted to their highest emitting sectors, and what key gaps exist within or across state plans?

- How did states fare when engaging in climate planning for the first time, and how much more work remains ahead?

- Which states show a high level of ambition? Are there new emerging climate leaders?

Though relatively high level, these early insights should prove inspiring for state policymakers and advocates by demonstrating the sheer volume of potential climate action contained within the 47 Priority Climate Action Plans. Over the next few months, our team will continue to review these plans to identify additional takeaways from across the country to further advance the transformative climate action these plans could unlock.