Author

Greg Casto ǀ Communications Manager

Indrani Malhotra | Communications Intern

Editors

Ruby Wincele ǀ Policy & Research Manager

Amanda Pontillo ǀ Communications Director & Operations Lead

Climate XChange’s Dashboard Digest is a deep dive on each of the policies that we track in the State Climate Policy Dashboard and an exploration of how these policies can interact with one another to form a robust policy landscape. The series is intended to serve as a resource to state policy actors who are seeking to increase their understanding of climate policies, learn from experts in each policy area, and view examples of states that have passed model policies.

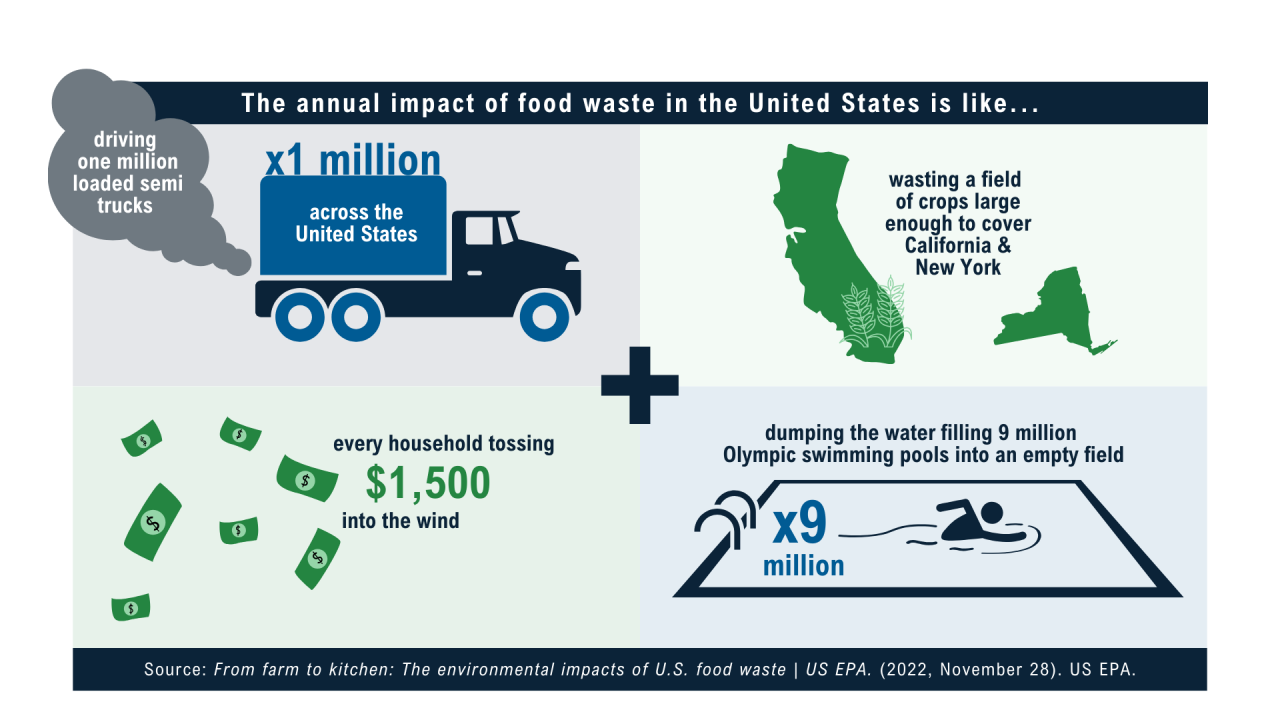

Nearly half of food produced in the U.S. is wasted each year. This waste comes from our homes, restaurants, universities, grocery stores — anywhere food is produced, packaged, and consumed. In fact, if global food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gasses in the world, following only China and the United States.

As food waste breaks down in municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills, it produces methane, a greenhouse gas more than 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. Landfills are the United States’ third highest emitter of methane, and more than half of those emissions come from wasted food.

States have a powerful policy tool to help solve this issue: food waste bans and targets. State governments can set goals for the reduction of food waste and even pass bans on the improper disposal of food waste altogether, both of which can promote more sustainable food disposal practices and even help redistribute still-edible food.

For this article in our Dashboard Digest series, we’ll dive deeper into why so much food is wasted in the U.S. and how states can divert organic waste from landfills to reduce emissions and food insecurity.

Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) landfills receive household and other nonhazardous waste.

LEARN MORE >

What are food waste bans and targets?

To reduce the amount of food waste that ends up in landfills, states have two similar, but distinct, policy mechanisms: food waste bans and food waste targets.

Food waste bans – States can directly prohibit the disposal of food waste into landfills, requiring waste generators to seek more sustainable alternatives. State regulations vary, but in most cases, bans only apply to facilities generating more than a given threshold of waste each week or year, including universities, grocery stores, and restaurants.

Food waste targets – States can also opt for food waste targets, which set objectives to reduce food waste by a certain percentage over a specified period of time, relative to a base year. For example, California set a target of 50 percent reduction in food waste by 2020 and 75 percent by 2025, relative to 2014 levels.

Both food waste bans and targets require waste generators to dispose of food in more sustainable ways through either reuse or recycling.

- Reuse — Food that is still edible can be redistributed to those in need, extra ingredients can be reused in creative ways, and surplus food can sometimes be repurposed into animal feed.

- Recycling — Inedible food waste can be recycled through composting or anaerobic digestion, both of which avoid adding to landfills.

Heather Latino, from the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, highlights that both bans and targets must be accompanied by the establishment of infrastructure to divert wasted food from landfills. She says that in order for food waste policies to be successful, “jurisdictions need to spend some time planning and understanding what resources are currently available and what gaps might exist.” Next, we’ll discuss the benefits and barriers to food waste bans and targets, as well as the key considerations for policymakers on this topic.

Anaerobic digestion is an alternative to composting which produces biogas as organic material is broken down. Biogas mostly consists of methane and can be burned for electricity, heat, or other forms of energy.

LEARN MORE >

Current States with Food Waste Bans and Targets

States with Food Waste Bans: California, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

States with Food Waste Targets: California and Washington.

Benefits of food waste bans and targets

State-level policies strive for a wide range of community benefits through the reduction of food waste. Heather Latino describes the environmental, social, and economic benefits of food waste bans and targets.

Environmental benefits

Although food waste only makes up about 24 percent of total MSW in the U.S., it’s responsible for 58 percent of all methane emitted from landfills. Diverting organic waste from the landfill avoids methane emissions, mitigating the effects of climate change and reducing local air pollution. Massachusetts’ food waste ban is reported to prevent over 3,300 tons of methane from entering the atmosphere each year, equivalent to taking nearly 20,000 gas-powered cars off the road.

Social and health benefits

Latino explains that food waste is also an environmental justice concern, and that disadvantaged communities can benefit from food waste programs that reduce food insecurity and promote workforce development through job creation.

The food that goes to waste in the U.S. could feed 150 million people, over four times more than the number of Americans who are food insecure. Environmental justice communities are more likely to lack access to the nutritious, fresh, and affordable food that is often sent to landfills. Food rescue and donation programs are one way to make sure that edible food reaches people in need, lowering household expenses and improving public health.

Economic benefits

Cutting down on food waste can result in savings for households, businesses, and governments alike. The average family of four in the U.S. throws $1,500 worth of food into the trash each year. Although, in most cases, food waste bans do not apply directly to households, public education campaigns and recycling infrastructure can encourage individuals to make more conscious purchasing decisions, and properly dispose of unused food. Commercial food waste bans can also help businesses reduce costs by encouraging them to purchase only what they can sell, and help conserve resources in the agricultural sector.

Organic waste bans can also lead to job creation in the industry. Massachusetts saw the creation of more than 500 new jobs in a six year period following the implementation of their organic waste ban, across the sectors of hauling, processing/composting, and donation.

Barriers to Food Waste Bans and Targets

Funding and Infrastructure

Properly disposing of food waste in recycling facilities can be expensive, and states may lack the infrastructure necessary to achieve ambitious goals. Many states don’t have sufficient existing facilities for composting or anaerobic digestion, and construction of such facilities can be cost-prohibitive (a large composting center processing up to 40,000 tons per year can cost $5-9 million to build). Private facilities can be utilized for waste processing, but without state-level policies in place it may be difficult to assure investors these facilities will be profitable.

Still, it’s clear that keeping organic waste out of landfills is a high priority for states across the country. Landfill diversion was the third most common measure listed in the Priority Climate Action Plans submitted by 45 states as part of the Inflation Reduction Act’s Climate Pollution Reduction Grant Program. While not all of these measures received implementation funding from the EPA, these states are signalling that there is a need for additional investments.

Read more about how states can reduce barriers and create demand for renewables and other investments.

LEARN MORE >

Compliance, Monitoring, and Enforcement

Monitoring all commercial food waste generators in a state can be nearly impossible, however without proper monitoring and enforcement, generators may dispose of food waste improperly or not make the effort at all. Salvaging organic waste for recycling can be costly and labor-intensive.

States can ease the burden of enforcement by entrusting responsibility to local municipalities, however coordination between state and local authorities may complicate enforcement processes, especially if regulations differ significantly.

Lack of Information

A lack of information on current amounts of food waste can also present a barrier to states intent on passing bans and targets, and make it difficult to accurately gauge the efficacy of the laws that have passed.

It’s impractical or even impossible for states to know the exact quantity of food waste that ends up in landfills due to the bulk nature in which it’s disposed. States and municipalities can attempt to find out by conducting surveys of major waste generators and extrapolating the results for the whole jurisdiction. For example, the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery, publishes the state’s waste characterization studies, which are voluntary and non-random, introducing some degree of bias in the results.

Key Policy Considerations

Heather Latino breaks down four key considerations to ensure food waste bans and targets are as effective as possible:

Have infrastructure in place — It’s important for states and municipalities to determine if and how existing infrastructure can integrate with food waste bans and targets, and what additional infrastructure is necessary to meet desired policy outcomes. If the infrastructure is insufficient, it may be necessary to provide government grants or incentives to help facilitate infrastructure development so that food waste generators can comply with the policy.

Municipal, county, and local support of food waste management — Action from municipal and other local governments can be a precursor to state-level policies, as they can promote better practices for reducing food waste, apart from a state-level ban. Washington’s food waste target, passed in 2022, came after Seattle’s organic waste disposal ban, which went into effect in 2015. Infrastructure and programs from the earlier ban can help the state achieve its ambitious goal.

Public education programs — It’s important to educate the public on how to identify expired food, how to correctly dispose of food waste, and the environmental, social, and economic benefits of food waste programs. Public education is invaluable both for residential and commercial generators in order for everyone to know the law and to be able to comply with it.

Stick vs carrot approaches — Lawmakers need to decide whether their enforcement mechanisms will be based on penalties or incentives, or better yet some combination of the two. These can include fees on improper disposal of food waste and tax incentives for donating edible food.

State Example

Massachusetts

Massachusetts’ food waste ban, established in 2014, requires all commercial generators of food waste (greater than 0.5 tons per week) to dispose of it through composting or anaerobic digestion facilities. According to a 2024 study, Massachusetts was the only state with a food waste ban that led to an overall reduction in total municipal solid waste (MSW) from 2014 to 2018. During this time, the state’s overall MSW fell by 7.3 percent, and methane emissions from the waste sector have declined by more than 20 percent since the ban first went into effect.

The state’s success has been attributed to the affordability of composting programs, the clarity of the policy itself, and the establishment of strong enforcement mechanisms and monitoring systems. Massachusetts also offers technical assistance to businesses that struggle with compliance through the state’s RecyclingWorks program.

The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection created an Organics Action Plan to comprehensively address organic waste disposal, and reported in 2023 that annual diversion of food waste has more than tripled from 2014 to 2022 and food rescue has increased by more than 50 percent.

A 2024 study that analyzed the effect of existing state-level food waste bans found that Massachusetts was the only state that saw a significant reduction in total municipal solid waste (MSW) from 2014-2018. Critics point out that because the study analyzed total MSW without separately measuring organic waste, other states may have seen a reduction in food waste that wasn’t captured by this analysis. Plus, Latino says that food waste bans are a relatively new policy tool, and many state laws weren’t in effect until after 2016. Still, the study’s results highlight some of the ways Massachusetts has set their program up for success.