Bill Gates is among a list of billionaire investors from all over the world betting on meatless burgers and plant-based alternatives for meat lovers.

The company behind the ‘bleeding’ plant-based burger is Impossible Foods, a Silicon Valley venture with a mission to make plant-based alternatives for meat lovers through science. It raised $75 million in funding last year in a round led by Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund Temasek. The latest round brings up the company’s funding to nearly $300 million, with earlier investors including Bill Gates, Li Ka-shing, Dustin Moskovitz and UBS.

Impossible Foods is not alone, Beyond Meat is another business, also partly funded by Bill Gates, aimed at replacing animal protein with plant protein substitutes. Their products are already widely available in supermarkets and restaurants in the United States and their massive flows of investment seems to be betting on their expansion into the mainstream. In Boston, these products are already available at retailers such as Whole Foods and Star Market and at restaurants Clover and Whalburgers.

These are not your average veggie burgers. Both companies are finding ways to create in labs entirely plant-based meat substitutes without having to compromise or change people’s carnivorous cravings. And both companies aim to provide a sustainable alternative to meat that is more sustainable and environmentally friendly but still caters to the taste of people who love eating meat. More importantly, they provide an option to enjoy a delicious burger with 95% less land, 87% lower greenhouse gas emissions and 74% less water than its beef counterpart.

The significant investment betting on plant protein, signals not only a higher awareness of climate change, but also a change in market demands for better tasting meat substitutes and an opportunity to embrace changing dietary patterns as a business opportunity.

The Meat Of The Problem

The impacts of the meat industry on the climate have been widely studied and written about, and yet there is a fundamental gap in how that knowledge translates – or rather doesn’t translate – into behavioral changes of well-meaning, climate conscious consumers.

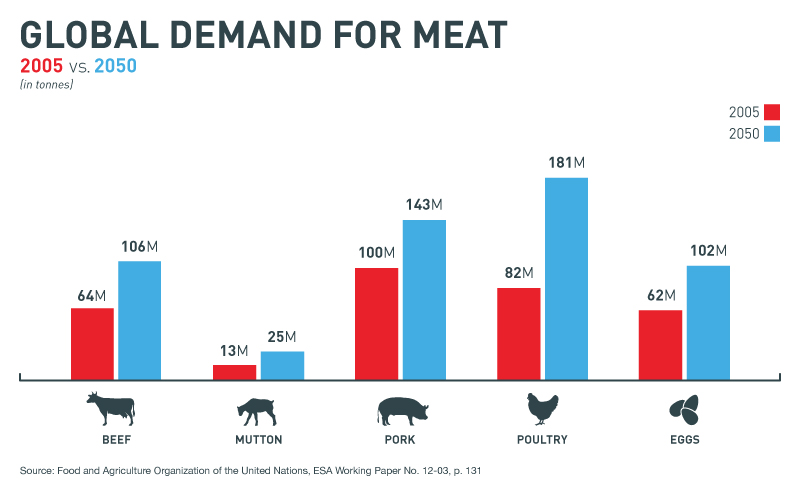

Research suggests that reducing global meat consumption will be critical to keeping global warming below the ‘danger level’ of 2 degrees Celsius, as outlined in the Paris Agreement, and yet the appetite for meat is growing. It is forecasted that by 2050, global meat consumption will rise by 75 percent, meaning that feeding ourselves will end up consuming a huge slice of our remaining carbon budget. It is therefore imperative that food becomes a more meaningful part of the climate conversation.

Raising animals for meat produces as much GHGs per year as exhaust emissions from all the vehicles in the world. So why is it that we talk about switching gas for electricity in our cars but not about switching beef for beans in our plates?

Food systems are a major driver of climate change, accounting for nearly a third of all human-driven GHG emissions. Raising animals for meat produces as much GHGs per year as exhaust emissions from all the vehicles in the world. So why is it that we talk about switching gas for electricity in our cars but not about switching beef for beans in our plates?

Raising and feeding livestock requires a lot of land and is a main cause of deforestation, resulting in habitat loss and species extinction. This has been the case in huge swathes of the Amazon rainforest, which have been torn down to raise cattle. According to the United Nations, 33 percent of arable land in the world is used to grow feed for livestock and 26 percent of the ice-free terrestrial surface is used for grazing animals. This amounts to about one third of land on Earth being used to produce meat and animal products. What if, instead of using so much of our precious land on growing single-crops that end up feeding animals, we used it to grow more fruits and vegetables that can feed us?

Beef accounts for the largest carbon and GHG emissions as well as for the majority of agriculture-driven deforestation, and is thus the most carbon emitting animal protein. Many have therefore argued for reducing beef consumption and switching to other animal proteins such as pork or poultry to be more environmentally friendly. However, there are also serious environmental and health concerns associated with raising pigs and chickens.

Impacts On Human Health

Beyond just the impact of food production on the health of our planet and its remaining ecosystems, current levels of meat consumption are detrimental to our own personal health. Processed meat for instance, has been classified by the World Health Organization as a Group 1 carcinogen – the same category as tobacco and asbestos.

Overconsumption of meat and dairy products has also been linked to the rising numbers of non-communicable diseases such as obesity and type-2 diabetes. These diseases have, beyond devastating personal pain and suffering, tremendous social costs and constitute an emerging public health epidemic.

Moreover, the industrialization of animal production has resulted in widespread use of antibiotics, which not only has repercussions to human health, but also has increased antimicrobial resistance, posing an immense threat to public health as well as increased treatment costs.

The Economic Case For Vegetarianism

Many will argue that feeding the world is a crucial necessity and therefore we must continue producing as much meat as required to meet the world’s protein needs. However, this logic is deeply flawed. One third of the calories produced in the world – and half of all plant protein – is fed to animals, and only a small fraction of those calories end up feeding humans. Moreover, plant protein is much healthier and rich than animal protein, at only a fraction of the environmental – and monetary – costs.

While it is hard to monetize the value of reducing climate change or individual health benefits, an Oxford University study found that following current diets – rather to shifting to more plant-based foods – could cost the U.S. between $197 billion and $289 billion every year. When scaled up to the impacts on the global economy, that number becomes $1.6 trillion by the year 2050.

The researchers calculated the direct health-care costs from conditions resulting from meat-heavy diets, as well as indirect costs due to lost work days. At the same time, they quantified the costs of reducing GHG emissions from meat production, using a measurement called the “social cost of carbon”. The idea is to estimate the value of repairing future damages caused by each additional ton of carbon put into the atmosphere.

There is a growing trend and interest in restaurants and vendors adopting more plant-based menus. Forget about the overpriced, millennial stereotype of vegan and vegetarian restaurants – there is an opportunity for every kind of food supplier to embrace more plants than animal proteins. In fact, it can be more economical – and more sustainable- than animal product-based food. By refocusing on local production of fruits and vegetables, we can drive their prices down and support local farmers. We can buy foods that are in season and in fact save on our grocery bills by cutting out expensive animal products.

Moreover, companies such as Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat have opened the pathway towards delicious, innovative alternative that increasingly make plant-based foods more similar in taste, appearance and texture as meat. If we go by investor confidence, it is safe to say that this trend will undoubtedly continue to increase, and there are significant market opportunities to ride that wave.

The Good News

Photo via Impossible Foods

Tackling unsustainable meat consumption offers a win-win scenario for both reducing the impacts and drivers of climate change and also tackling some of the most pressing public health issues. Reducing meat production could close the emissions gap by a quarter by 2050, freeing up some of our carbon budget and lowering the costs of mitigation across other economic sectors.

The good news is that unlike the huge systemic changes needed to address fossil fuel emissions in other sectors, dietary changes can be made at the individual level and immediately. We do not need policymakers or investors to agree on a way forward, and there are already plant-based meat alternatives on the market to make the transition much easier.

Ultimately, whether or not you decide to change your diet, it is important to have this conversation and be aware of all the factors that go into our personal and business contributions to climate change. By understanding the carbon footprints of our diets, we can make choices that are better aligned with our principles and our larger understanding of the issues we all face due to climate change.