Climate change lies at the intersection of humans and nature. The Earth is a patchwork of ecosystems that combine to create one living, breathing being. And the atmosphere is its lungs. A delicate balance exists between our atmosphere, soil, and water and plants act as a valuable connection keeping all systems coordinated – capturing carbon and releasing oxygen, cycling water and nutrients. When one component of the patchwork is thrown off balance, the entire system reacts.

Climate change lies at the intersection of humans and nature. The Earth is a patchwork of ecosystems that combine to create one living, breathing being. And the atmosphere is its lungs. A delicate balance exists between our atmosphere, soil, and water and plants act as a valuable connection keeping all systems coordinated – capturing carbon and releasing oxygen, cycling water and nutrients. When one component of the patchwork is thrown off balance, the entire system reacts.

Think about your morning routine. You showered, got dressed, ate breakfast, commuted to work. Everything you did has a carbon footprint. The electricity used to heat your water, the fuel used to power your car or the train, the supply chains used to produce your clothes, all creates greenhouse gas emissions. Even your breakfast generated emissions, from the farm where your food was grown, to the supermarket you purchased it from, to the energy you used to cook and prepare it. Now think about the impact humans collectively have on our atmosphere.

We have known about climate change and its potential impacts on our livelihoods on Earth for decades, and yet little has been done to meaningfully change the practices that cause it. It is now projected that at current levels of greenhouse gas emissions, we will surpass 1.5 degrees celsius of warming above pre-industrial levels by 2030. This is the temperature that has deemed to be the peak at which our planet can continue to sustain human livelihoods. Beyond this point, our delicate patchwork of ecosystems will fail to function in the ways we have become accustomed to.

As a child, my perception of nature was the forests of Western Massachusetts and the Appalachian Mountain Trails that run through them, where I grew up. I spent afternoons climbing trees and examining the pattern of veins that extend through leaves. Naturally, my college years were spent in a biology lab continuing this examination, as an Environmental Biology and Geography major. I am still fascinated with how plants wield their leaves as a tool to not only survive, but thrive in their environment. I studied how different leaves function –– what happens when they receive more water, more carbon, more predation. I found their complex and intricate systems captivating.

However, I felt something was missing from my research. When setting up studies, it was common practice was to attempt recreating a pristine environment, one free from human interference. I found the notion of a pristine environment perplexing. Humans have touched almost every corner on Earth, either directly or indirectly through atmospheric influences. At even the deepest depths of the ocean, exploratory divers have found trash. Pristine environments didn’t interest me, because they do not represent real conditions of the world we live in. I wanted to examine the symbiotic relationship between people and plants.

When I graduated and moved to Boston, I didn’t want to continue working in a lab. Researching how climate change will impact humans and the environment is a critical component of tackling the issue, but I wanted to somehow be involved with implementing changes derived from these scientific findings. My search brought me to the Massachusetts Legislature, working for the House Committee on Climate Change. I came to the position with an entirely scientific background, knowing nothing about politics and learning policy along the way.

When it comes to climate change, science and politics occupy different worlds entirely. I arrived on Beacon Hill on the precipice of a session promising action on a large renewable energy procurement bill. Throughout the two-year session, as language determining the future of solar, wind, and hydro power was debated, I found scientific studies and statistics were made to bend and mold narratives arguing on both sides of the renewable debate. Science transitioned from a concrete exploration for truth to another social construct, where any figure could be interpreted in a myriad of ways. Moreover, the amount of information produced on a layered and complex field like energy was nearly impossible to sift through with enough scientific rigor to decidedly determine the right course of action. Bridging the gap between the lab and the legislature seemed an insurmountable task.

I also repeatedly heard climate change labeled as a secondary concern. People justify diverting focus from our changing climate because there are so many more pressing issues in the short term. The timescale of atmospheric changes and their corresponding impact on our ecosystems is thought of as a problem we can deal with in the future. How can we focus on an environmental issue when society is tearing at the seams today?

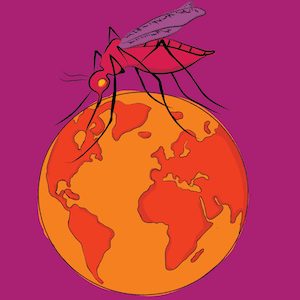

The reality, however, is that climate change already touches the lives of everyone on the planet, slowly compounding and multiplying the issues we already face. The impacts are already being felt –– sea level rise influencing housing markets; harsher storms occurring with more frequency; shifting geographic ranges for crops, fish, and disease-harboring insects.

Last year, I left the legislature to work at Climate XChange, a small non-profit that occupies the second and third floors of Old West Church, a two-hundred-year-old structure located on the back side of Beacon Hill. We focus on researching and advocating for market-based mechanisms for reducing carbon emissions, leading the movement on state-level carbon pricing.

How to talk about climate change is a question that comes up in the office very often. Yes, we are in a dire situation, and that should be communicated. But painting a situation of doom and gloom is not always a conducive way to work towards solutions. We may be beyond the tipping point for greenhouse gas emissions, but by throwing our hands up and admitting defeat, we will miss any opportunity we have to tackle and solve the climate crisis. For this reason, we have mobilized to focus on real solutions – whether that be new strategies for adapting to its impacts or reducing emissions.

Cooler Earth the podcast was born from these conversations.

We wanted to move the climate change discussion beyond the academic and political realm and tie it to the issues that we all care about in the present. We set out to elucidate the ways climate change intersects with a myriad of other pressing social and geoeconomic issues. On the podcast, theories like energy democracy and social capital are explored, bridging the gap between conversations surrounding social and environmental issues and the ways in which they intersect.

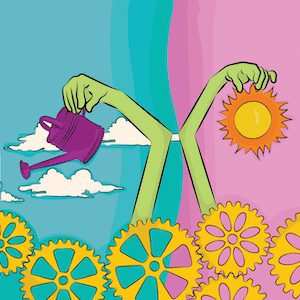

The look of the podcast had to reflect the optimism we aspired to foster in our audience. We wanted Cooler Earth to be a broad platform for reaching a wider audience on their terms. I knew that the visual appearance of the podcast would be crucial in drawing listeners in. This initially took shape with the bright colors of our podcast thumbnail, appearing in an altered thermal temperature map of the world. I also wanted a way for us to engage new listeners with every new episode. Creating illustrations depicting the theme of each episode was a natural way to inject more color, life, and art into the podcast. When you visit the homepage, you are greeted with playful imagery that evokes a sense of excitement and joy. Before even listening to an episode, you are immersed in a positive and optimistic atmosphere, which frames the experience we want our audience to have with the project, and moves away from the more traditional forms of climate change communication.

While working in the legislature, I was constantly confronted with communications challenges – how to convey technical and scientific information in an accessible way and how to get legislators and staffers in a room to hear that information. I found myself addressing those issues with visual solutions, creating bold meeting invitations and infographics. Graphic design was a natural tool for communication and I wanted to learn how to best wield the tool in the world of politics and advocacy. When creating Cooler Earth, I was able to fully realize the power of imagery in communications, drawing people in by creating a particular mood and using art as a tool to help convey crucial information.

As millennials, we have inherited climate change from the generations that came before us, and I believe solving it will be our greatest challenge, and hopefully also our greatest accomplishment. The artwork of Cooler Earth evokes the optimism and perseverance we will need to create a world that thrives in the face of this obstacle. We have the potential to not only create solutions to adapt to our changing atmosphere, but to address the larger social issues that currently threaten equity and justice with our solutions. The science that details what will happen as we emit more greenhouse gases is scary, but we can’t let that deter us. Art has the power to open our conversations surrounding climate change to a wider audience than we ever imagined possible. And what we need to achieve equitable solutions is a wide audience and diverse opinions. After years of examining the scientific and political angles of this issue, Cooler Earth is my solution to the communication challenges surrounding climate change.

Cooler Earth is available on all streaming platforms. Check out Season 2, airing Thursday, November 8th.