The Transportation & Climate Initiative (TCI) is a regional initiative in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic to reduce transportation emissions through a cap-and-invest program. For more information on the program, check out our other articles on TCI or our recent comment letter submitted to TCI leadership.

This Thursday, the Transportation Climate Initiative and Georgetown Climate Center held a webinar to review the various modeling assumptions used to craft a “reference case” for emissions in the region. A vital first step in policy design, the reference case projects what transportation emissions will be in the future absent the program.

This is a pivotal moment in the process – all decisions made about the program’s final design, including cap stringency, price floors and ceilings, and other technical decisions, will be informed by the reference case. What emissions are projected to be in the future will inform states on what level of reductions they think are feasible.

The technicality of this conversation can be overwhelming at times. Slides are full of jargon and acronyms – VMT, LDVs, and ZEVs to name a few – which can make it difficult for people to substantively participate in the conversation. With so many stakeholders involved in the TCI region, however, it is vital to keep all aspects of the modeling process transparent and open to public comment. Let’s break this process down, talk about why reference cases matter, and highlight best practices for TCI moving forward.

Key Takeaways

- TCI is about to model the projected emissions of the region. We can derive lessons from previous cap-and-trade systems on how to use the reference case properly moving forward in TCI.

- Getting year one emissions right is pivotal in order to avoid an early oversupply of allowances. We should be wary of the delay between when the program is implemented and when the reference case is modeled.

- We cannot predict the future, and any reference case will likely be wrong. Building review periods into the program allows administrators to calibrate the cap trajectory and maintain the program’s effectiveness.

- Previous experience has shown us that emissions reductions tend to outperform expectations. Whether this will be the case for transportation emissions is yet to be seen.

The reference case is just a “best guess”

The unfortunate truth is that we cannot predict the future. Historically, models have had a tough time accurately predicting baseline emissions, particularly more than 10 years in advance. So many factors heavily influence the program’s outcome, yet are full of uncertainty – economic growth, technological advancement, fossil fuel prices, and changes in federal policy can all create significant swings in a given state’s emissions trajectory.

In order to project emissions, we have to make sweeping (and sometimes arbitrary) assumptions about what the world will look like in the future. The TCI reference case should be considered our “best guess” of emissions, rather than a prophecy of the future.

If designed well, cap-and-trade can handle this uncertainty while still achieving our climate goals. The program works by requiring companies to submit allowances, or pollution permits, for their annual emissions. By offering a diminishing number of allowances each year, governments can let the market decide how to keep emissions on track for the lowest cost. If we reduce emissions faster than we expected, then the supply-demand balance relaxes and carbon prices ease downward. If we end up emitting more than we expected, then the carbon market picks up the slack through increased allowance prices.

TCI is a bit tricky in that we’re not yet sure what the climate goal for the program should be. How ambitious can this program get without allowance prices getting uncomfortably high? What level of impact do the TCI states need from this program in order to significantly contribute to their respective climate goals for 2030 and beyond? The answers to these questions are heavily informed by the reference case modeling stage.

We’ve gone through this process before – both the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) and Western Climate Initiative (WCI) underwent extensive modeling exercises during the design phase of their respective programs. We should learn from our previous experiences in order to design TCI the right way. What have we learned from previous cap-and-trade reference case modeling exercises?

Year one emissions are important to get right

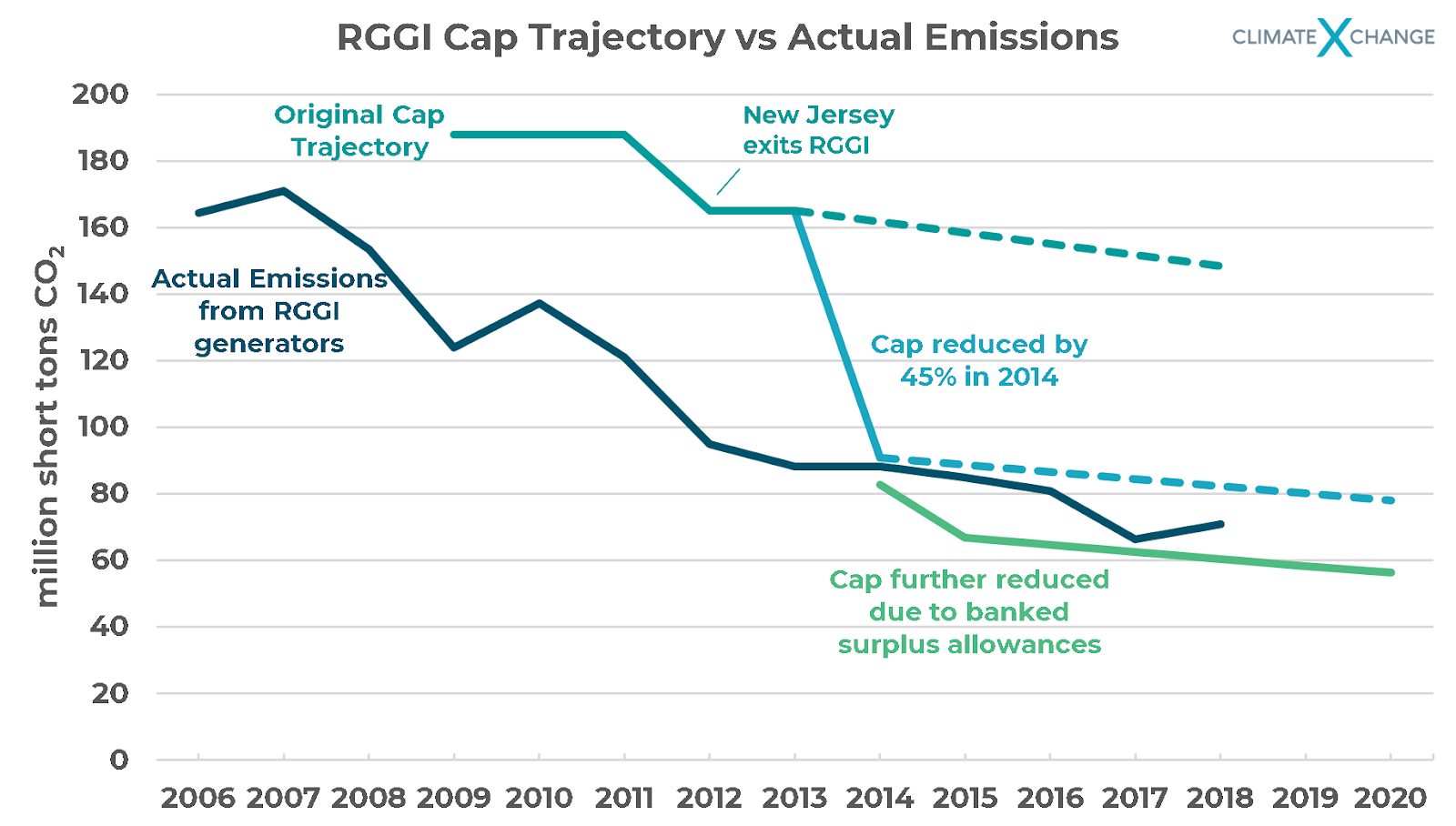

RGGI, WCI, and virtually every other cap-and-trade program has set the initial cap too high. If a cap-and-trade program begins with an excessively high cap, polluters can save surplus allowances and use them in future years instead of reducing their emissions. While the decision to set a cap excessively high is based in politics just as much as (if not more than) science, we’ve seen reference case models misstep on year one emissions before.

Sources: RGGI COATS & Program Design Archive, RGGI.org

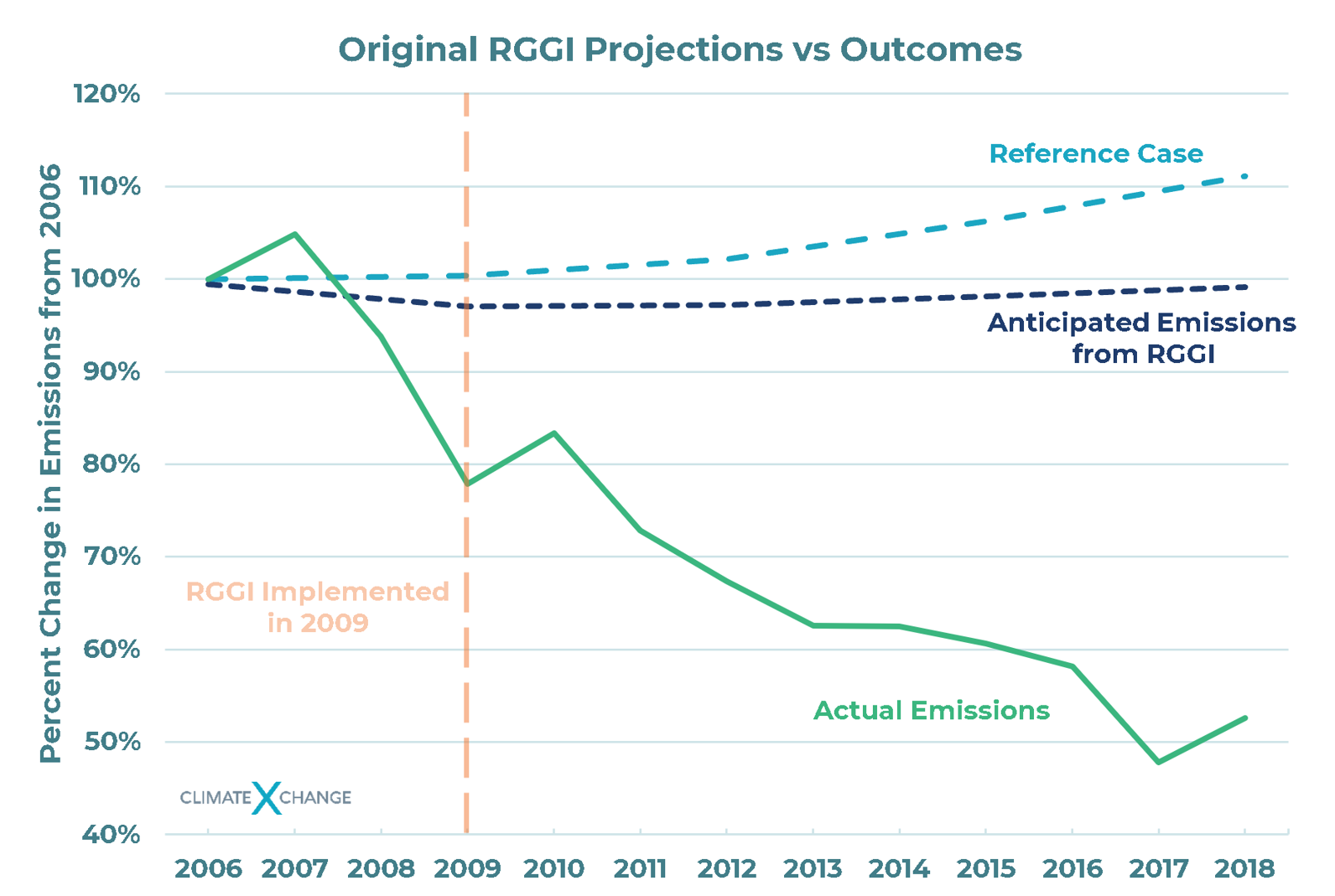

The reference case completed in 2006 for RGGI did little to account for the phenomena unfolding before, during, and after the program launched in 2009, such as the economic downturn combined with the proliferation of cheap natural gas replacing dirtier forms of electricity generation. As a result, the program was severely overallocated in early years.

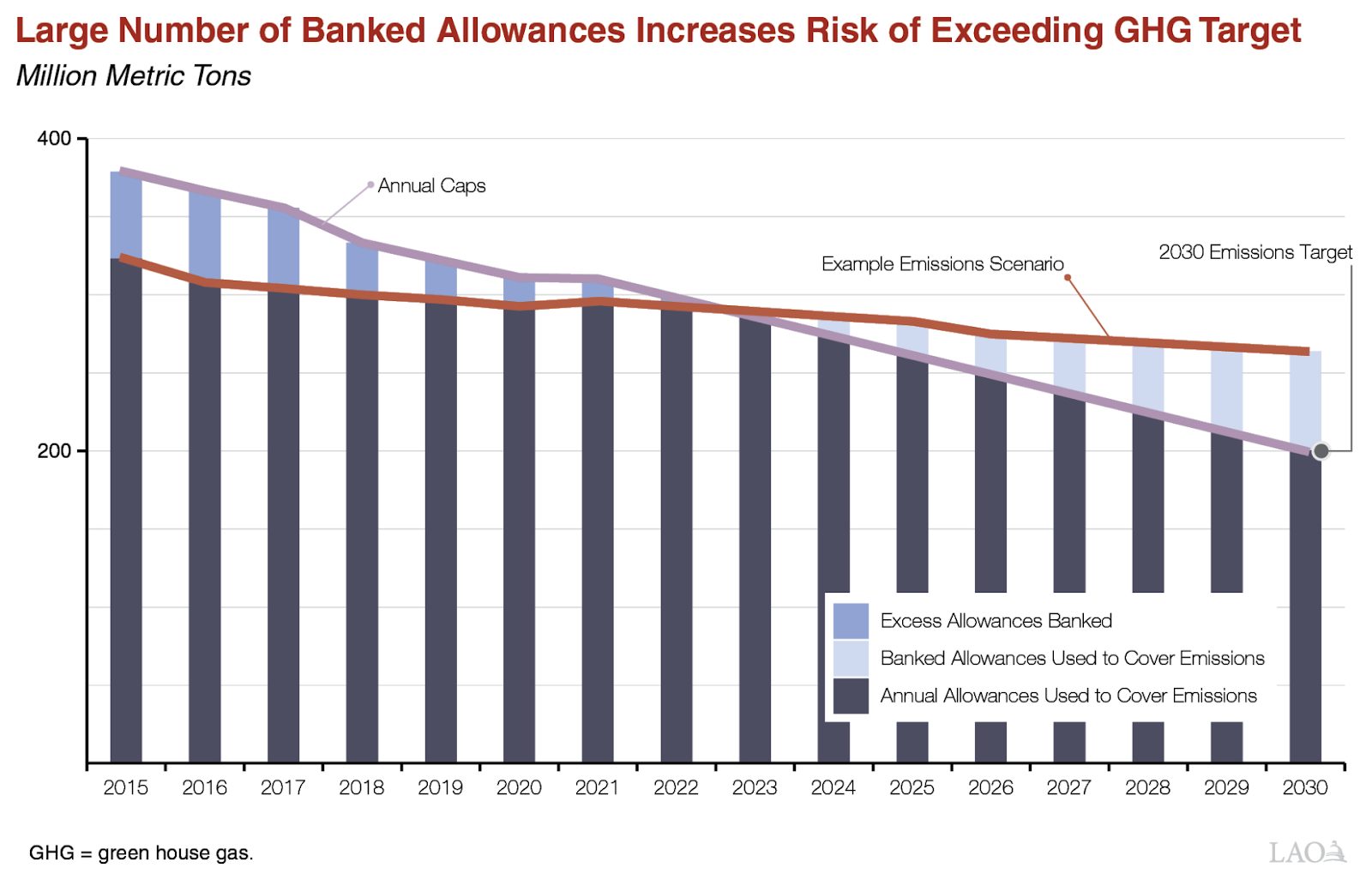

California’s business-as-usual case did a far better job at setting year one emissions at the right level – they simply averaged out emissions between 2009 and 2011 in order to predict emissions in 2012. However, due to CARB’s political decision to set the initial cap high, as well as some unforeseen drops in electricity sector emissions, California found themselves significantly overallocated by the time their program expanded to the entire economy in 2015. This problem has continued to grow – currently, the program has hundreds of millions of tons of CO2 accumulated as surplus allowances, threatening the ability of the program to achieve reduction goals later on in the program.

Source: Ross Brown, Cap-and-Trade Extension: Issues for Legislative Oversight. Legislative Analyst’s Office, Dec 2017.

More importantly, prepare for your projections to be wrong

There are two key dynamics at play here. First, the reference case prediction is often wrong. In both RGGI and WCI, emissions have reduced faster than expected, particularly in the electricity sector. This is a good thing in that emissions reductions should always be celebrated – as long as the program is then adjusted to ensure it stays effective. Early reductions can create an excess of banked allowances, compromising the program’s ability to spur reductions in later years.

Second, there are strong political pressures to set the cap higher than necessary. In the face of uncertain reference case predictions, would a public official rather go with an aggressively low cap, risking the creation of a volatile, expensive carbon market from day one? Or would they rather ease into the program by giving the initial cap a bit of wiggle room.

Combined, these two factors are why virtually every cap-and-trade system has been overallocated. However, the program can still be effective by scheduling periodic reviews of the program, with the opportunity to adjust the cap upward or downward based on unexpected emissions outcomes or a banked supply of allowances.

Sources: RGGI COATS, Program Design, RGGI.org

In RGGI, the cap has been adjusted downward multiple times in order to keep the program effective amongst an unforeseen drop in demand for allowances. The transparent review process is something to be replicated in TCI and other prospective programs – every 3 years, the RGGI states review the latest data on how the program is doing, re-model the future outcomes of the program, and make adjustments to the cap accordingly.

California, on the other hand, has not addressed their currently growing bank of surplus allowances, leading experts, stakeholders, and legislators to increasingly call for better transparency and consideration of the issue. Despite boasting the strongest carbon pricing program currently running in the United States, California has at times demonstrated an unwillingness to work with concrete evidence and legitimate concerns raised by these groups.

What does this mean for TCI?

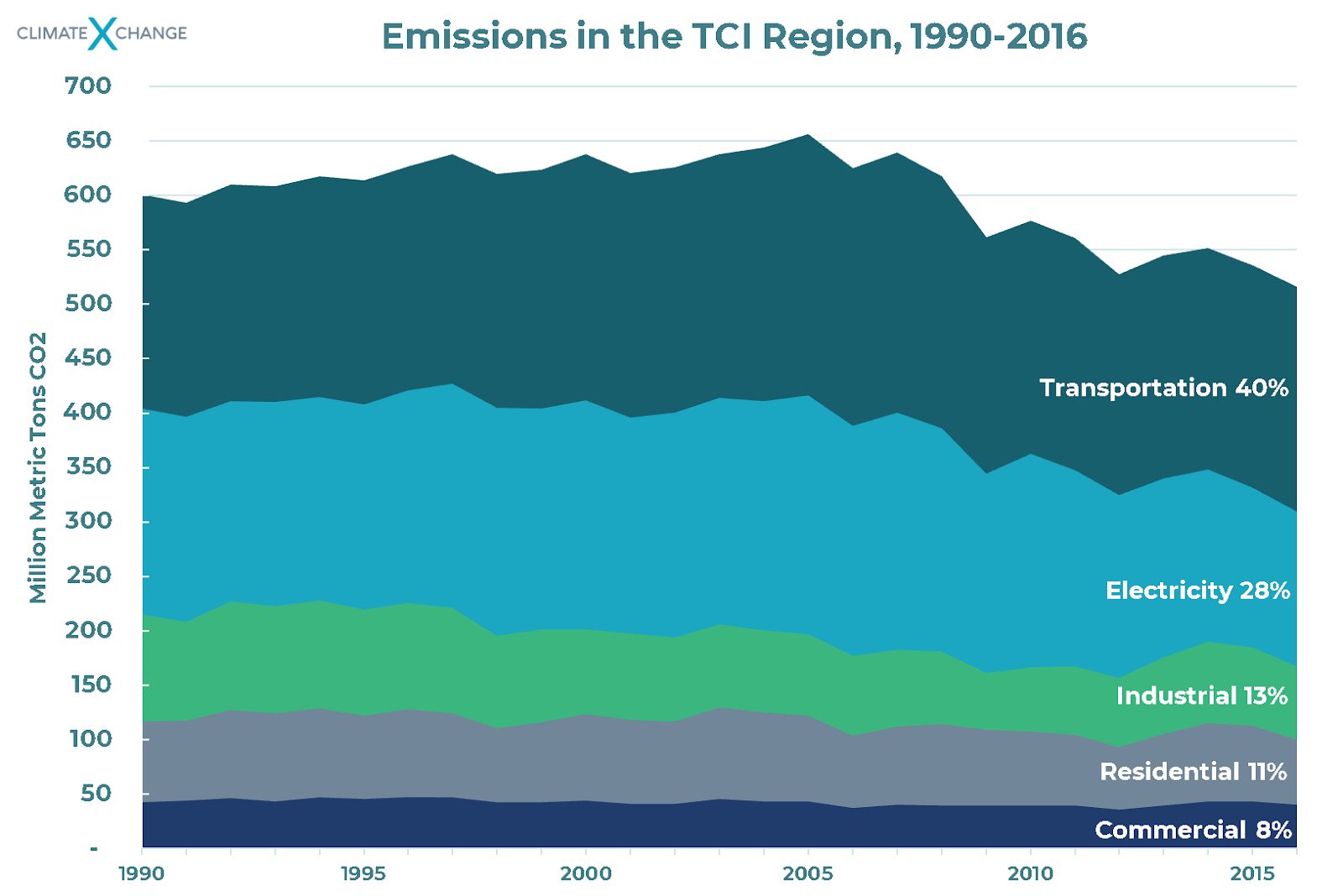

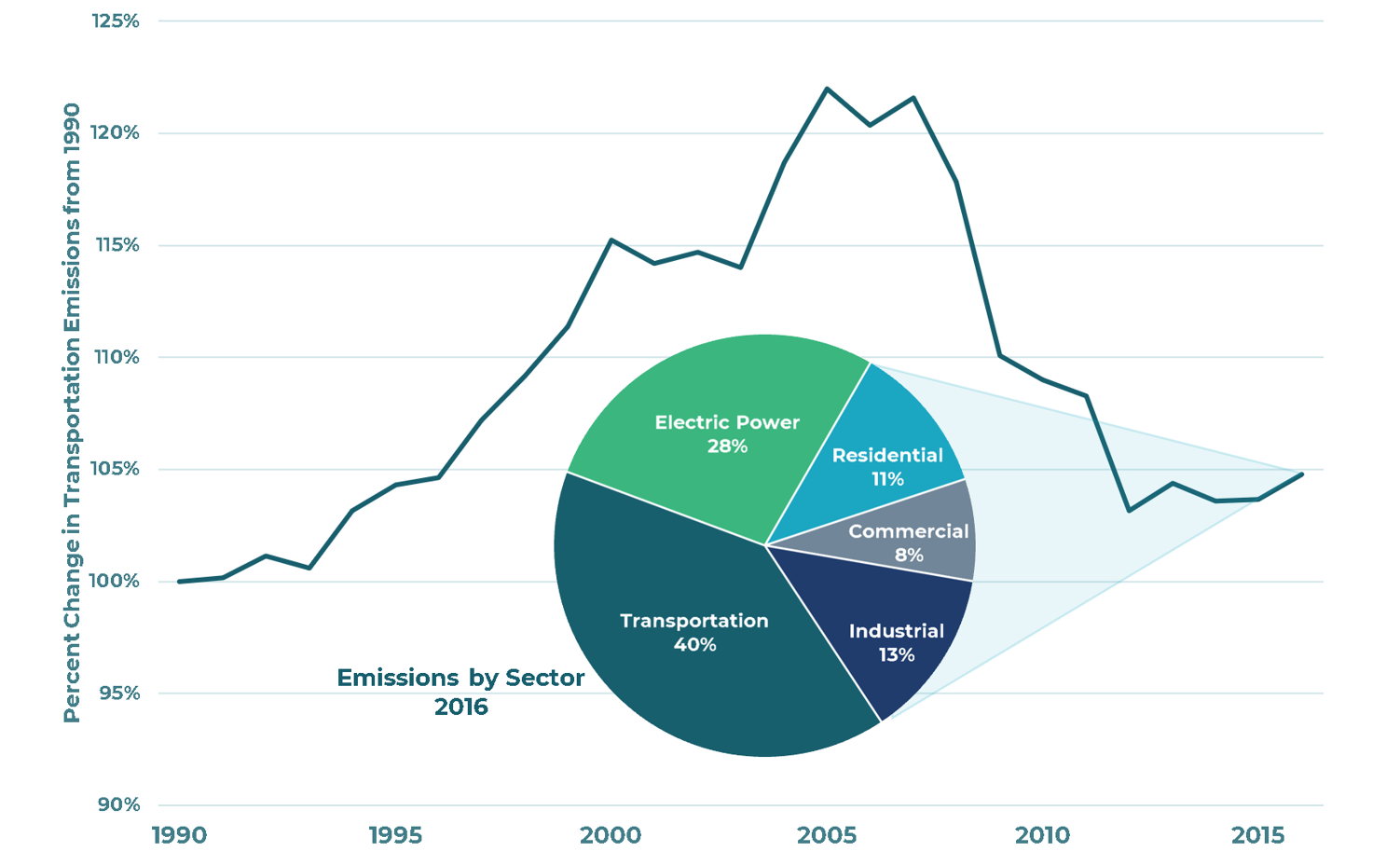

The stage is set for the reference case in the TCI region to play out in a similar fashion. Transportation emissions have slowly increased since the end of the recession, and conventional economics views gasoline consumption as fairly “resistant” to price changes, meaning that in order to achieve the reductions that we need, we may need a carbon price higher than officials would prefer to impose.

Source: EIA State Energy Data System

Source: EIA State Energy Data System

Should the reference case model bare out this trend, states will negotiate later this year over a cap trajectory that is “safe”, and likely unsatisfactory to meet our climate goals. But if history is any indication, we can, and need, to do better than “safe”. As long as we follow the learning lessons of previous programs, strive for data-driven transparency, and prepare to adjust the program in future years, then we can lay the foundation for an effective market-based policy to make real contributions towards the reductions and transformations our region needs.