This week, world and business leaders headed to Madrid for the two-week 25th Conference of the Parties (COP) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). For almost three decades, governments from around the world have been meeting each year to envision and agree upon global responses for the climate crisis – some COPs have been incredibly notable, like the 2015 Paris negotiations, while others have been much less fruitful.

In the landmark 2015 Paris agreement, nations committed to keeping global warming below 2°C (above pre-industrial levels). The legally binding agreement has now been ratified by the vast majority of nations in the world, yet individual countries’ contributions – Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs – are up to each country.

The UN’s latest emissions gap report, published ahead of COP, highlights another critical issue for global carbon emissions: even under perfect implementation, under current national commitments, the world is guaranteed to see an estimated temperature rise of more than 3°C by the end of the century. The report finds that countries will need to reduce their greenhouse gases by about 7.6% each year for the next 10 years, to stay within the 1.5°C limit.

And while in the past five years, great strides have been made in terms of figuring out the rules and guidelines under which Paris will be implemented, now the international community faces another quite challenging task: raising overall ambition and push countries to go beyond current NDCs.

Article 6 Negotiations at COP 25

The main subject up for discussion at this year’s COP is Article 6 – a provision within the Paris agreement that regulates the modalities of voluntary cooperation among Parties to promote mitigation ambition as well as sustainable development. It outlines a few ways in which countries can do this:

- [Article 6.2] Parties can engage in bilateral or multilateral “cooperative approaches” when implementing their NDCs through the trade in mitigation outcomes. Essentially, if one country is able to reduce emissions beyond the amount promised in its NDC to the Paris Agreement, another country can purchase these additional reductions to count towards its own NDC.

- [Article 6.4] Countries can authorize emissions reduction activities within their territories, which would include financing for sustainable development projects that can also be used for emissions reductions. Read our in-depth analysis on carbon offsets

- [Article 6.8] In addition to climate action and climate change adaptation, under this non-market approach, Parties can also use much broader cooperation strategies, including technology transfer and capacity-building measures in other countries.

Hashing out the details of these cooperation mechanisms would allow for countries to cut emissions through trading in emissions reduction strategies for mitigation outcomes, while providing avenues for financing of clean technology and energy projects around the world. The latter is particularly important in the context of development funds for nations in the global south, and if properly done, could result in sustainable financing mechanisms that could also reduce carbon emissions and prevent fossil fuel development.

Carbon markets have been around since the 1997 Kyoto protocol, and there is already trading happening in a bilateral and regional basis, but specific negotiations on this article under Paris have been stalled. One of the main goals of COP 25, therefore, is to agree on how to account for previous market efforts under the CDM, develop a common system for accounting trade in emissions outcomes, setting standards for those trades, and ironing out other outstanding potential issues.

What are we anticipating?

The lynchpin to the Paris Agreement is the concept of Nationally Determined Contributions, country-set ambitious goals to reduce national emissions and commit to climate action. It is critical that countries set a high bar for the level of ambition to their NDCs and cooperate across borders on strategies. While climate change is global in impact, carbon reduction costs are not uniform, and in fact vary greatly across countries and regions. This is reflected in Article 6 by allowing countries to trade Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes, known as ITMOs. What this means is carbon reductions in one country – through offsets, land management, or other carbon reducing policies – could be bought and sold across jurisdictions, therefore allowing NDCs to be met through the most optimized and lowest cost options.

Carbon offsets from land management and forestry have dominated the conversation around transnational emissions-reducing opportunities, however mitigation outcomes can take many different forms. Energy efficiency projects, low carbon energy generation, and pollution reduction from food production, are just a few examples of the kinds of projects that could meet emission reduction verification protocols. These avenues will have much larger implications specifically for the reduction of global emissions, keeping temperatures below 2°C, and the way we conceive of and finance global development and advance sustainable development goals.

Two things are clear: first, if nations in the global south are to continue developing using fossil fuels and polluting practices, we will surely surpass 2°C of warming and fail to reach emissions reductions targets globally. Second, the cost of reducing carbon pollution, or offsetting it, is much, much lower in those very same countries.

This means there is a huge opportunity to tackle the overall goals of the Paris Agreement through emissions trading schemes, and we should embrace it. In order to do so, mechanisms must be agreed upon to set robust accounting systems to prevent or mitigate some of the challenges that may arise from them. Transparency, credibility, and trust must be baked into this process, as well as critically framed in the context of global climate and security threats.

Key concerns

Double counting

Double-counting has been raised as an issue constantly when it comes to carbon markets, particularly as it relates to the use of offsets. The concern here is that carbon offsetting would potentially be counted for more than one country’s NDCs and therefore not truly capture the real carbon emissions being offset by one particular project, and preventing proper accounting of emissions.

Mechanisms to prevent against double counting are also crucial. The country selling emissions reduction credits and the one purchasing them should not both be able to count them towards their NDCs. There must be adjustments to account for this in ITMO transfers, due to the huge importance of tracking and transparency in the final market design. As discussed under ITMO transfers in Article 6.2, one valuable approach to ensure environmental integrity in a carbon market is to adopt partial cancellation of credits when they are transferred, so that neither Party claims the emissions reduction and there is an overall mitigation in global emissions.

Lack of meaningful ambition on emissions reductions

Another key concern often cited when it comes to carbon markets is that they could allow for countries to continue polluting as long as they purchase carbon credits elsewhere, essentially “letting them off the hook”. However, when talking about limiting carbon dioxide in the atmosphere globally, as long as emissions are in fact cut, the source of them should not necessarily matter.

While it is certainly true that all countries should be doing their share to decarbonize their own national economies, we are currently under an extremely tight timeline to reduce emissions and avoid worst-case scenarios of warming. For this reason, it is important to capitalize on the fastest and most economically feasible ways to reduce those emissions – especially if we are able to do so while advancing Sustainable Development Goals around the world.

Previous market challenges & opportunities

Parties currently disagree whether or not ITMOs will be a tradable commodity promoting the emergence of an international carbon market. This is a key point that needs to be resolved and agreed upon as it will also result in important implications on how the mitigation outcomes will be transferred. Under the conception that they can be a traded commodity, actors outside country governments would technically be able to enter the market and also trade in these outcomes. The alternative would be to keep them as solely government to government transfers with the specific goal of reaching NDCs and sharing emissions reduction outcomes.

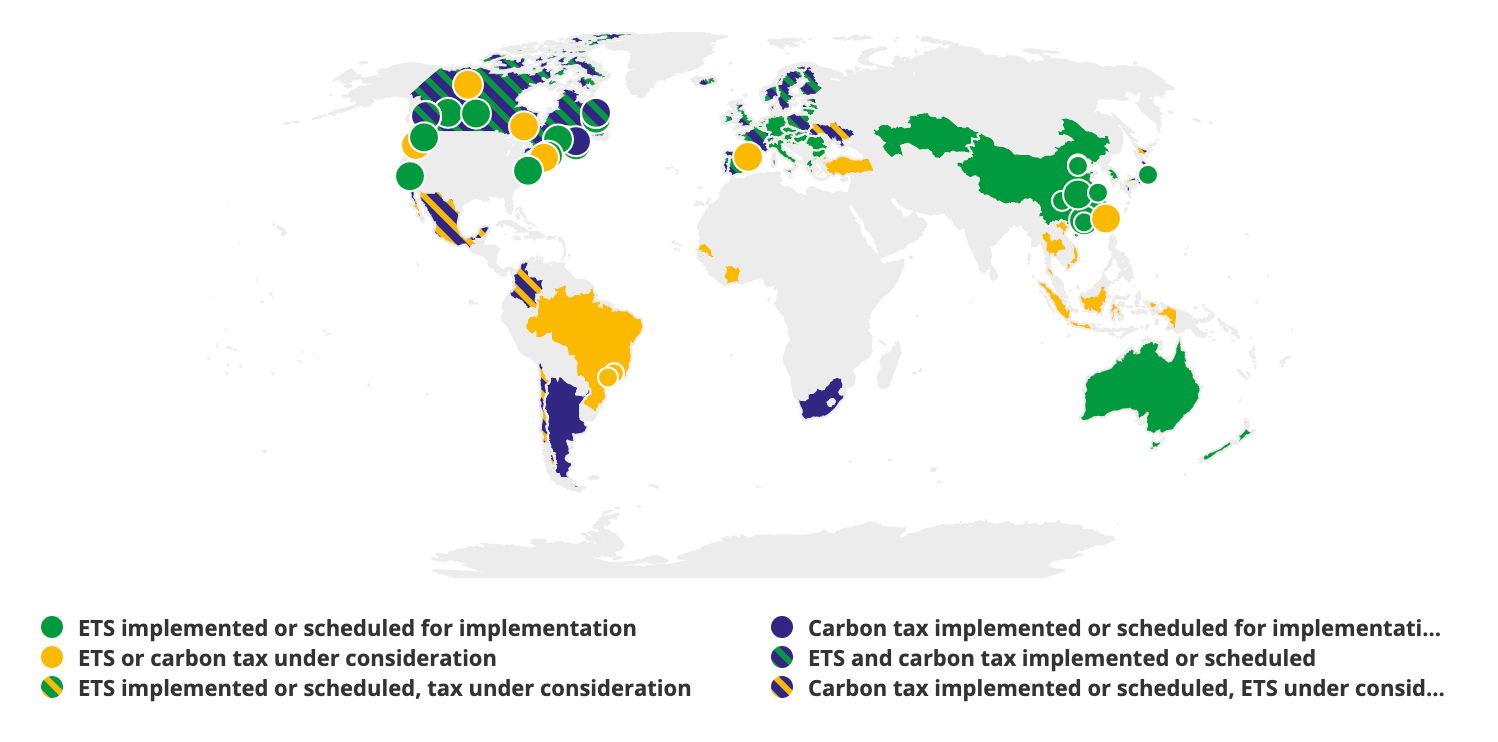

There are currently 46 countries and 28 subnational jurisdictions around the world that already have a form of carbon pollution pricing. Harmonizing these while learning from best practices through their experiences will be a critical point in the finalizing of article 6 negotiations. Ideally, through this we can set a high floor upon which to build a robust cooperation mechanism.

Some of the older markets have run into serious challenges in terms of accounting and implementation across borders. The EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), launched in January 2005, is the first international emissions trading scheme covering about 40 percent of EU emissions. The program, along with some smaller ones, has historically run into issues on price signals being too low to actually have an impact on emissions reductions (something that has also been seen in the Northeast United States in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative).

Some markets are being developed with great ambition and high prices, like The Korean Emissions Trading System (KETS). Launched in 2015, KETS is the second largest in scale after the European Union Emission Trading Scheme, and is currently trading at USD 20.62 per t/CO2e and has begun trading with several cities in neighboring Japan.

Current carbon markets are only going to continue growing and likely expand into other jurisdictions; it is crucial that these negotiations at the international level embrace this wave of policy and use it to raise the bar for ambition and learn best practices from those that are already under way. Even in the absence of positive outcomes from COP, trading will continue happening on a regional and bilateral basis. We most likely won’t get every rule agreed upon in Madrid, but that does not mean countries should shy away from pursuing implementation and going above and beyond whatever is negotiated. Both at the national and subnational level, leaders who want ambitious outcomes from this COP can in fact pursue them at home and make them a part of their emissions reduction plan.

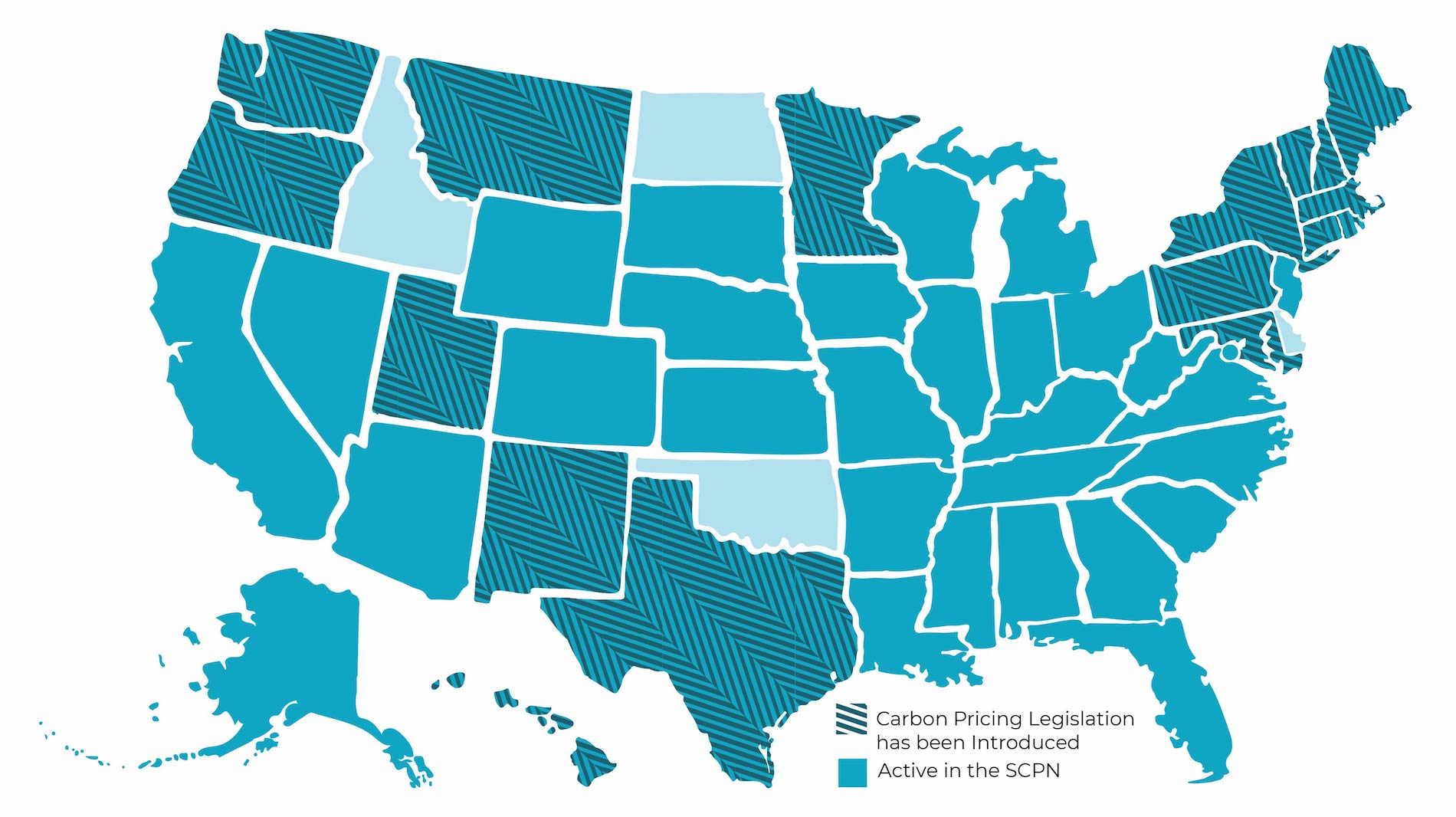

In the U.S. this year alone, 16 states introduced carbon pollution pricing bills, and we expect that number to grow next year. We have been working closely with stakeholders involved in legislative, executive branch, and regional carbon pollution pricing across the country, gaining insight and compiling best practices and guidelines for everything from program design decisions to community engagement and public buy-in.

Now what?

Ultimately, an ITMO is about cooperation, and it can be a pathway to reduce global emissions fast, which is what we crucially need right now. For this to occur, there needs to be mechanisms in place to ensure best practices and enable equitable cooperation between the global north and south. Unleashing financing avenues and sharing technologies and best practices in emissions reductions will become an increasingly important climate solution in the coming years and decades.

Moreover, we now recognize we’re running out of time to take meaningful action on this issue. The framework and cooperation resulting from the Paris agreement, and negotiated every year at COP, are, while far from perfect, the only avenue we have for this level of multilateral engagement and cooperation. It is incredibly encouraging to see the public pressure and momentum that is building, particularly from youth organizations demanding real results from our leaders. Hopefully it can translate into action, and we can head into 2020 with the frameworks necessary to get to work on meeting and exceeding NDCs globally.

As our team heads to Madrid later this week, we will continue to bring you updates on the ground, and are excited to report out on the development of the negotiations. Be sure to follow our social media, and subscribe to our newsletter for the full scoop.