As the prevalence and severity of climate-related emergencies rise, so does the need for awareness, diversity, and inclusion to be woven into the fabric of the climate movement. Understanding the systemic inequities that create barriers to accessibility for the disability community, such as eco-ableism and lack of inclusion in policymaking, is necessary to bring about impactful change.

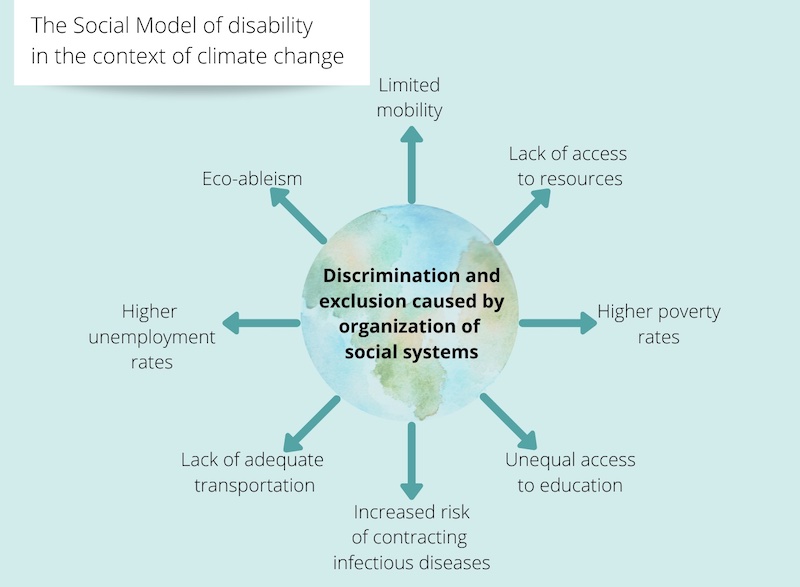

According to the United Nations, approximately 15 percent of the global population is disabled. The disability community is diverse, including those with physical, sensory, cognitive, and psychological conditions, as well as various chronic conditions. Since the 1970s, the Social Model of disability has challenged the stereotype that people are disabled only by the limitations of their bodies. Reframing this perspective, the model highlights the social barriers of disability, and the responsibility of society and institutions to make accommodations that enable accessibility.

Disabled People Are More Vulnerable To Climate Impacts

Disabilities create multidimensional impacts, and experts agree that the entire disability community is at greater risk of suffering from the negative impacts of climate change. It’s imperative that disabled people have access to education on disaster response, communicating with emergency responders, and self-care at a level that is least restrictive and appropriate. Every disability and experience creates a unique situation, and even well-trained responders will need a way to communicate with individuals about their specific needs. A disabled person is two to four times more likely to die or be critically injured in a climate-related disaster due to lack of access to information, lack of transportation or accessible emergency shelters, and mobility limitations.

Those with disabilities are more likely to encounter hardships during evacuations or migrations due to limited mobility and impaired senses. This is a result of inadequate training of emergency response personnel, improper equipment for evacuations, and a misunderstanding of the diverse needs of the community. Communities often do not properly assess risk to determine which residents need extra support during climate emergencies, and emergency responders are then ill-equipped to carry out rescues. When family members and neighbors evacuate, they leave vulnerable populations without support networks and disabled residents in isolation, which creates immediate safety concerns.

Temperatures are on the rise, and so are occurrences of heatwaves across the country — such as the June 2021 heatwave in the Pacific Northwest. As temperatures soared well above 100℉, the demand for electricity also soared, causing rolling outages across the region. The region’s normally moderate climate and weather patterns mean many residents are without air conditioning (AC) units, and many who did have access to an AC system were unable to use it due to power outages. Hundreds of lives across the region were lost to hyperthermia, or abnormally high body temperature. Extreme heat has major impacts on those with preexisting conditions and is one of the deadliest forms of weather. A Stanford University Medical School study found a causal relationship between rising temperatures and increased fatigue and pain in people with multiple sclerosis. Dehydration brought on by high temperatures can increase glucose levels and decrease the ability to absorb injected insulin for diabetics. Thermoregulation, or the ability to maintain one’s own temperature, is often impaired in individuals with spinal cord injury, which is compounded with exposure to high levels of heat.

On the other extreme, increasing incidents and scale of winter storms also create barriers for the disability community. Extreme cold in Texas in February 2021 inhibited travel by in-home health workers and medical delivery services. Extended power outages due to the state’s inability to meet demand also posed a significant risk to residents who use medical devices that require electricity. Without electricity, residents found themselves unable to charge electric wheelchairs, power home oxygen systems, and use life saving dialysis machines.

As the impacts of climate change increase, so will the prevalence of related impairments leading to disability caused by disease and injury. For example, warmer temperatures and increased humidity will result in the spread of mosquito-borne illness, which can result in chronic conditions. Underlying conditions also make disabled people more susceptible to contracting these infectious diseases.

Where the Climate Movement Intersects with Ableism

One young activist is doing her part to tackle this problem. There’s a page in her baby book highlighting photos from her first protest, so it’s not surprising that 18-year-old Izzy Laderman is still advocating for justice. As a young teen, Laderman was involved in the U.S. Youth Climate Strike organization. It was during this time that she realized the disability community was often an afterthought, or even completely left out of the climate justice conversation. She also noticed how difficult self-advocacy was without an organized group supporting her cause. This prompted her to start an organization called Disability Awareness Around the Climate Crisis (DAACC).

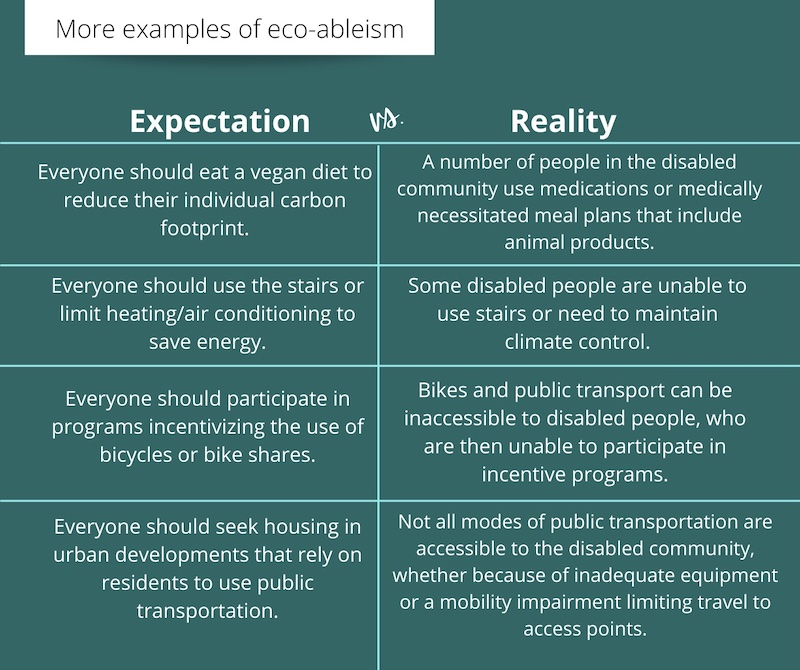

Laderman told Climate XChange that she formed DAACC “because the conversation about policy and solutions needs to include disabled people or they’re going to be left behind.” The organization’s current goal is education and awareness. With the help of her mother, a social studies teacher, Laderman created lesson plans on eco-ableism, which she uses in training sessions. A majority of the DAACC training participants are already involved in climate advocacy, but they might not understand how eco-ableism is contributing to the systemic crisis.

Simply put, eco-ableism is applying ableist views to the environmental movement, which is often the result of a lack of diversity. One very popular example is the waste-free movement. The move to ban plastic straws does not take into consideration those who cannot use straws made of other materials because of allergies, sensory disabilities, or requirements for flexibility in the straw. People whose disabilities necessitate the use of medication that is administered through single-use plastic or distributed in medicine bottles cannot sacrifice these life-saving interventions. Laderman believes, “People are focusing too much on individual action when systemic change is what’s really going to make an impact.” She hopes that DAACC training will help raise awareness of common ableist views so participants can go back into their communities and educate, increasing the understanding necessary to lead to systemic changes.

Disabled people face systemic inequities that stem from the improper distribution of power and resources and lack of diversity in positions of power. Exploring the social and economic drivers that lead to the marginalization of and discrimination against disabled people is the first step in creating solutions. Many disabled residents are living in poverty and unsafe conditions, which make them even more vulnerable to climate change impacts. Disabled climate migrants are often forced to settle in low-income areas where climate risks already have disproportionate impacts, as well as fewer employment opportunities and limited support networks. Ignoring the social justice component of the climate crisis means that policy will be ineffective, and will only continue to create patterns of exclusion and injustice.

Ensuring Inclusion in Planning and Policymaking

Another goal of DAACC is to provide a community of disabled people for collective advocacy. “Group activism is more powerful,” Laderman explained. Disabled people are part of the conversation and need to be listened to, and further, they need representation in leadership roles.

In 2015, the United Nations Office of the Commissioner of Human Rights created a list of obligations for governing bodies to follow to ensure that climate action was rooted in equity. The UN suggests a twin-track approach when developing policy. Track one creates policies specific to empowering disabled people by providing accommodations or removing barriers to accessibility, but the implementation of those policies alone will not create systemic change. That can only happen when policies include a second track, which mainstreams inclusion into all stages of planning and policy creation with the advice and guidance from a diverse representation of the disability community.

Climate change adaptation planners and policymakers will need to use innovative solutions to create disability-inclusive programs. The first step in doing this is to include disabled people in the discussion and creation of preparedness plans. Current disaster risk mitigation and resilience plans include disabled people under the term ‘vulnerable,’ but do not reference the diverse needs of this community. Each person’s capacity for adapting is dependent on their access to resources, which is often inhibited due to mobility issues, lack of a support network, or lack of education.

An inclusive preparedness plan should contain:

- A framework for educating the disability community on disaster response (including how to communicate their needs to emergency responders)

- Disaster response education for caregivers and other household members

- An equitable resource distribution plan

- An inclusive, community-level resilience office

- Rescue groups trained on providing accessible rescue strategies

- Risk assessment and planning for proper identification of vulnerable people

- Community-level dissemination plans that allow for disbursement of information related to impending or ongoing disasters

- Guidelines for dissemination of information between various levels of government

System-Level Change Leads to Inclusive, Sustainable Policy

State and community-level disaster preparedness plans often leave out the disability community or include them as an afterthought. After repeated disasters in recent years, some states are implementing policy related to resilience planning that includes specific considerations for the disability community. Creating new plans or restructuring existing ones to address impending issues is essential as climate-fueled disasters become more frequent.

Many response strategies are considered first-track policies, addressing immediate needs by enabling accessibility for all. Systemic changes are also necessary to ensure sustainable progress, including:

- Advocating for inclusion in the distribution of climate funds and resources

- Addressing discrimination and attitudinal barriers

- Working to end the cycle of poverty and disability (strong correlation)

- Ensuring equitable access to appropriate education for disabled people and their caregivers

Climate change is undoubtedly the defining issue of this century, and due to the diversity of individual experiences, it is truly an intersectional crisis. Climate change not only exacerbates disabilities and leads to the development of disabling impairments, but it can be life-threatening to disabled people. Those with disabilities may not have adaptation resources and often face daily struggles due to a lack of adaptive or inclusive infrastructure. Different disabilities require different adaptation and accessibility equipment as there is significant diversity within the disability community.

Disabled perspectives should be included in climate change policy discussion as nobody knows their needs better. As a member of the disabled community, Izzy Laderman has experienced exclusion and the pain of being overlooked. She turned her frustration into action with the founding of DAACC, and has identified ways she and others in her organization can make a difference. Through this group, her individual action has become collective and empowers others in their activism. “At the end of our training, I ask each person to share one thing they learned and one thing they will take back into their community,” explains Laderman. “And their answers inspire me.”

Author’s Note: There is debate about the use of person-first versus identity-first language. With respect for Izzy Laderman, as well as the preferences of others consulted during the research process, identity-first language is used throughout this article.