This article was submitted by a member of our State Climate Policy Network (SCPN) — a rapidly-growing program within the organization that includes more than 16,000 advocates and policymakers across the country who are pushing for effective and equitable climate policies in their states. The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Climate XChange.

Interested in submitting an article to be posted on our website?

Note: This was originally published by the Progressive Policy Review — a student publication at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Authors: Vanessa Warheit, Andrea Marpillero-Colomina, Marc Geller, Sven Thesen

Abstract: Electric Vehicles (EVs) provide environmental benefits to society while simultaneously providing direct health and financial benefits to drivers who adopt them. While California’s progressive state policies have accelerated EV adoption, historic bias continues to be embedded in California’s “CALGreen” building code — effectively delivering the most benefits of EV driving to already-affluent single-family homeowners, who are predominately white. A statewide coalition is currently working to address this disparity by influencing the 2022 CALGreen building code update cycle — an effort that seeks to remedy long-standing economic, health, and environmental inequities and to support California’s ambitious greenhouse gas reduction goals.

Introduction

Transportation is the largest source of California’s greenhouse gas emissions; pollution from this sector also contributes to smog and particulate pollution, which pose significant health risks that fall disproportionately on low-income communities and communities of color. To help clean up the transportation sector, California has issued a series of laws and executive orders over the past seven years, mandating an ever increasing number of light duty Zero Emission Vehicles (ZEVs) in the state. In 2014, SB 1275 called for 1 million ZEVs or near-ZEVs by 2023. Four years later, with 238,000 electric vehicles (EVs) and 5,525 fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) on California’s roadways, Governor Jerry Brown increased that goal with Executive Order B-48-18, calling for 5 million ZEVs by 2030. More recently, in September of 2020, Governor Gavin Newsom issued Executive Order N-79-20, requiring all new light duty vehicles sold in California to be ZEVs by 2035. With continuing declines in battery pricing, an accelerating climate crisis, and increasing awareness of the economic, environmental and health benefits of ZEVs, there is now a push to move that deadline up from 2035 to 2030.

These increasingly ambitious orders raise, but do not answer, an obvious question: how will California drivers charge all those EV’s? They also raise some less obvious but equally important questions: how can that charging infrastructure be equitably deployed? And once deployed, how can we ensure that low-cost electricity is available equally to all EV drivers?

Data on EV driving shows clearly that the majority of EV drivers charge their cars at home — yet not all drivers have access to home charging. In a recent Consumer Reports national consumer survey, 71% of drivers said they were interested in getting an electric car, but 48% said that lack of access to public charging infrastructure was holding them back, and 43% cited vehicle cost as a disincentive. It is not surprising, then, that the lack of public EV infrastructure has garnered increasing attention from policy makers (see, for instance, this recent op-ed in the LA Times); however, there remains a fundamental misunderstanding regarding where and how most EVs are actually — and most affordably, and conveniently — charged. According to Chris Harto, senior sustainability policy analyst for Consumer Reports, “American drivers are accustomed to having ready access to gas stations, and may not realize that if they have a personal garage or driveway, they’ll be doing most of their charging at home with an EV.”

It’s important to note that convenient home charging access also comes with significant cost savings: Harto authored a 2020 study highlighting the cost benefits of owning an EV vs. a traditional gasoline-powered vehicle, which found that “a typical EV owner who does most of their fueling at home can expect to save an average of $800 to $1,000 a year on fueling costs over an equivalent gasoline-powered car.” The same, however, cannot be said for drivers fueling at public fast-charging stations, where the cost of electricity (which, in California, is not regulated for EV charging) can equal or exceed the cost of gasoline on a per mile basis.

Residents of multi-family housing (MFH) often lack access to the convenience and economies of home-based charging – either because they lack off-street parking, or simply because their off-street parking lacks access to power. This lack of access translates into a cascading lack of financial, health, and environmental benefits which fall largely along racial lines.

In the US, Black and Latinx drivers are disproportionately low-income, less likely to own their home, more likely to live in multifamily dwellings, and more likely to live in segregated neighborhoods. All of these statistics also hold true in California, and the challenges for Black and Latinx drivers to gain access to EV infrastructure are formidable. For one, landlords are less incentivized than homeowners to provide EV charging in residential parking spaces, not least of all because the landlords would have an obligation to manage what is likely to be an unprofitable system for charging their residents’ vehicles. Despite passage of California’s SB1016 ensuring tenants the right to install charging infrastructure, residents of condominiums also face similar challenges to access, even when a certain percentage of parking is “EV capable.” Common obstacles to both apartment and condominium residents include: determining the availability of EV wiring and panel capacity; obtaining permission from the landlord/ Home Owners Association (HOA); ensuring access for their unit to wired spaces; and paying for and installing the wiring, circuit breaker and receptacle/EVSE. These are often insurmountable hurdles, even for the most determined resident. Changing the building codes for multi-family housing to provide more ubiquitous EV charging at the time of initial construction is therefore one important step in dismantling the structural inequities that perpetuate racial disparities in health and economic well-being in the US.

Building Codes: Expanding Affordable EV Infrastructure at the Lowest Cost

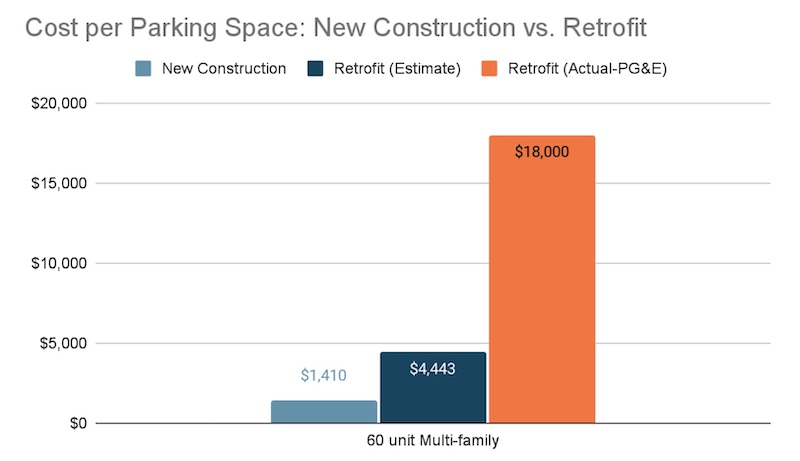

While charging at home is typically the most cost-effective and convenient way to fuel an EV, the most cost-effective way to build that access into residential parking is to do so at the time of new construction. A 2016 City of San Francisco study determined the cost of installing EV charging infrastructure via retrofit would be approximately four times what it would cost during new construction. Data from a subsequent PG&E retrofit program shows the actual cost of utility retrofits can be over twelve times higher.

Fig. 1 – EV infrastructure cost comparisons show actual retrofit costs in California are substantially higher than estimated, and exponentially higher than installing infrastructure at the time of new construction. Costs include wiring, switch gear, conduit, trenching, and secondary transformer, permitting etc..

Fig. 1 – EV infrastructure cost comparisons show actual retrofit costs in California are substantially higher than estimated, and exponentially higher than installing infrastructure at the time of new construction. Costs include wiring, switch gear, conduit, trenching, and secondary transformer, permitting etc..

Building codes tend to lag the built environment by three to six years, which means that codes being written in 2021 will define construction of new buildings into the mid- and late 2020s. Given California’s ZEV mandates — and the exigencies of the increasingly dire climate emergency — it is not a stretch to imagine that these buildings, in service well into the 2050s and 60s, will require retrofitting to accommodate electric vehicle charging in the fairly near future. Affecting the building codes now is therefore a critical step in the transition to electrified transportation, and ensures the infrastructure supporting the lowest cost power to the driver is installed at the lowest cost to the builder.

EV Charging Access for All Coalition and CALGreen

In late 2020, to address these issues, a small group of EV advocates launched the “EV Charging Access for All” campaign to achieve better and more equitable access to EV charging infrastructure in California’s building codes for new multi-family housing. Members of the EV Charging Access for All coalition had worked in 2018 and 2019 with local Community Choice Energy agencies to craft model municipal EV reach codes, which have helped to democratize and expand access to EV driving in over a dozen cities around the state. However, this piecemeal approach will not be sufficient to meet California’s ambitious EV targets, nor will it equitably distribute the economic and health benefits of EV driving. Leaving EV infrastructure building codes up to local jurisdictions also threatens to widen the equity gap — leaving behind communities where local leadership is either still largely supported by the fossil fuel industry or does not understand the economic and environmental benefits of EVs, as well as low-income communities that may lack the resources to adopt new reach codes. Patchwork reach codes can even risk increasing gentrification in ‘EV forward’ communities. The statewide goals clearly require a statewide approach.

A similar full-press effort was already underway to amend California’s building codes to increase building decarbonization — but this effort did not include EV infrastructure. Building electrification is covered by the California Energy Code, which is governed by the California Energy Commission; while EV infrastructure falls under a separate section of the California building code known as CALGreen.

CALGreen is California’s first-in-the-nation mandatory green building standards code, developed in 2007 in an effort to meet the goals of AB32, the California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006. California’s Housing and Community Development agency (HCD) is responsible for CALGreen in residential buildings (including hotels and motels). HCD receives input on CALGreen from the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and the Department of the State Architect, and final approval from the state’s Building Standards Commission. The CALGreen code is renewed on a three-year cycle, with intermediate 18-month ‘interim cycle’ reviews. The 2022 cycle is currently (as of publication) being developed, and is the primary target of the EV Charging Access for All coalition’s work to date.

The coalition’s principal demand:

Every new housing unit with parking, including apartments and condos, must have access to power at the parking space via an electric receptacle or EV charging cordset. Prominent signage must indicate the space is “EV Ready”.

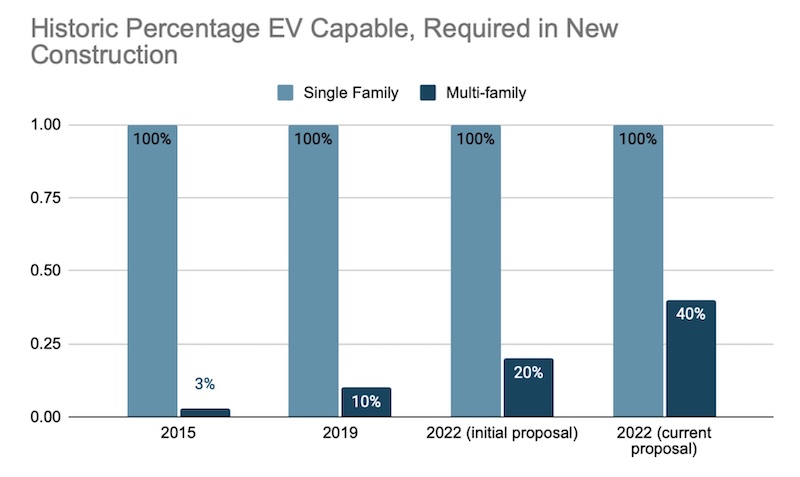

Fig. 2 – CALGreen has required 100% access for Single Family Homes since 2015, while the majority of California’s new Multi-Family Housing still lacks EV infrastructure.

Fig. 2 – CALGreen has required 100% access for Single Family Homes since 2015, while the majority of California’s new Multi-Family Housing still lacks EV infrastructure.

CALGreen has mandated, since 2015, access to power for EV charging in all new California single-family homes. However, it has lagged far behind in mandating access to power for charging in multifamily housing — starting with only 3% of spaces in 2015, and creeping up incrementally to a proposed 20% at the beginning of the 2022 code cycle. The coalition felt it was way past time for California’s multi-family residents to have equitable access to the benefits of electric driving.

Access and Equity Considerations for Residential EV infrastructure

Consumer confidence and community buy-in depend largely on where EV infrastructure is located, and on consumer education about how EV charging works and how much it costs. There will be no widespread buy-in and adoption unless the people who buy, drive, and depend on cars see themselves as EV drivers, and have access to charging infrastructure.

Unfortunately, for the uninitiated, EV charging infrastructure is intimidating — both because consumers are unfamiliar with what it entails and because there is a great deal of difference between types of EV charging. Whether there is even charging capacity available at all for multi-family dwelling residents largely depends on the decisions of landlords or an HOA to provide this infrastructure. The limitations on access to private charging — wherein the decision to provide this vital infrastructure is based on individual actors, rather than driven by public policy — perpetuates access inequities that have disproportionately affected low-income people and communities of color for generations. It is the 21st century equivalent of the cold water flat: until landlords were required by law to provide hot water, they had little incentive to do so since they bore the cost, and many tenants had no choice but to remain.

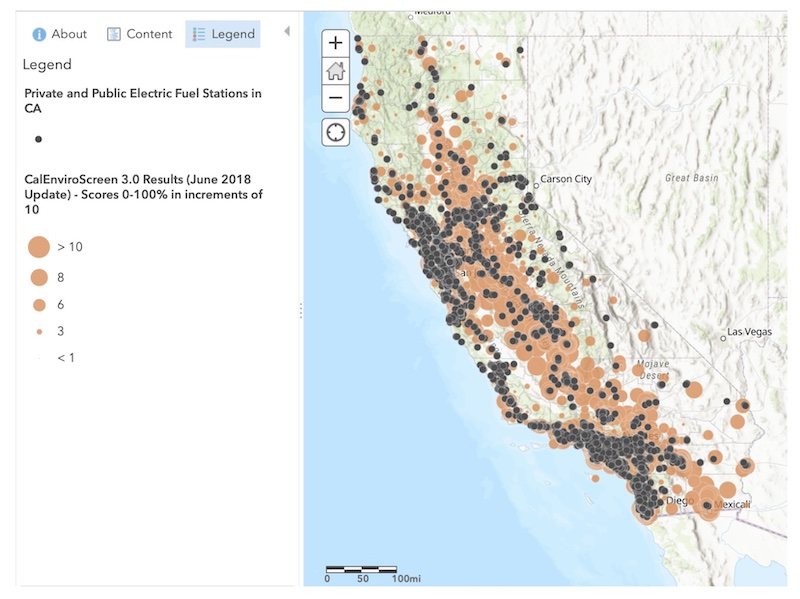

Multiple roadblocks must be addressed to create an equitable EV landscape — including changes to both public and private infrastructure. “Charging deserts” are a major barrier to EV adoption throughout the US, and California is no exception. Using publicly available data, the coalition created a map highlighting the discrepancies between disadvantaged communities (as defined by CalEnviroScreen) and California’s public and private charging infrastructure. (See Fig. 3.)

Fig. 3 – Disparities between EV charging infrastructure and disadvantaged communities. (Data mapping assistance by Tiernaur Anderson. Note that residential EVSE locations and “wall outlets” not designated for vehicle charging are not included in the Station Locator, but workplace charging locations are.)

Fig. 3 – Disparities between EV charging infrastructure and disadvantaged communities. (Data mapping assistance by Tiernaur Anderson. Note that residential EVSE locations and “wall outlets” not designated for vehicle charging are not included in the Station Locator, but workplace charging locations are.)

Unfortunately, much of the policy work regarding equitable access to EVs has centered exclusively on the need for public charging – ignoring the fact that the vast majority of EV drivers charge their cars at home, and that charging at home is the most economical way to fuel an EV. Because home charging is not just more convenient, but also enables access to the lowest rates offered by an electric utility, equity demands that multi-family residents be offered this same access.

Projects like a recent effort to install 100 charging stations at curbside locations on New York streets are important for increasing the visibility of EV driving; if people do not see or have access to EV infrastructure in the neighborhoods where they live, the likelihood that they will feel comfortable transitioning to this technology or that they will believe that EVs are “for them” are slim to none. But these efforts, while important, are not guaranteed to be affordable; nor do they address the underlying inequities built into our housing infrastructure.

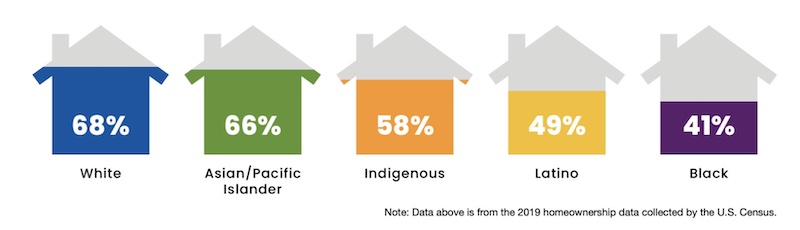

And while California is recognized for its progressive state policies, and its public attention to the climate crisis, California has not been as forward thinking when it comes to housing. From NIMBYism to restrictive building codes to the homelessness crisis, the state’s legacy is mixed at best. The extant disparities in homeownership by race in the state of California are significant (and not much different from nationwide trends). In 2019, California homeownership among whites was 68 percent, versus 49 percent for Latinos, and just 41% for Black Californians. Historic trends in discriminatory practices, including exclusionary zoning, predatory lending, and outright racial discrimination have created a housing landscape that is inequitable and inaccessible to many Californians. To adequately address and remediate the inequities that exist, the state must enact residential building codes that seek to redress the limitations placed on renters, particularly those who are low-income and often subject to the whims of policymakers, landlords, and other private sector actors. Enacting building codes to provide equitable EV infrastructure access should be an integral piece of that effort.

Fig. 4 – Home Ownership in California, by Race

Fig. 4 – Home Ownership in California, by Race

The EV Charging Access for All coalition is therefore advocating for equitable building codes which acknowledge that parking access and decision-making power for multi-family residents is different than it is for single family homeowners. An equitable multi-family housing code would mandate the following:

- wiring an EV space directly to the corresponding housing unit’s electricity meter;

- installing true EV Ready ‘plug-and-play’ charging access;

- making that access available to every new unit with parking; and

- prominently labeling EV charging access with highly-visible signage.

Without this kind of equitable access, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx drivers are more likely to be left behind or to be completely excluded — while wealthier, white homeowners reap the immediate benefits of at-home EV charging and the state fails to achieve either its climate goals or the societal benefits of electrified driving.

Cost/Benefit Analysis and Actions Taken

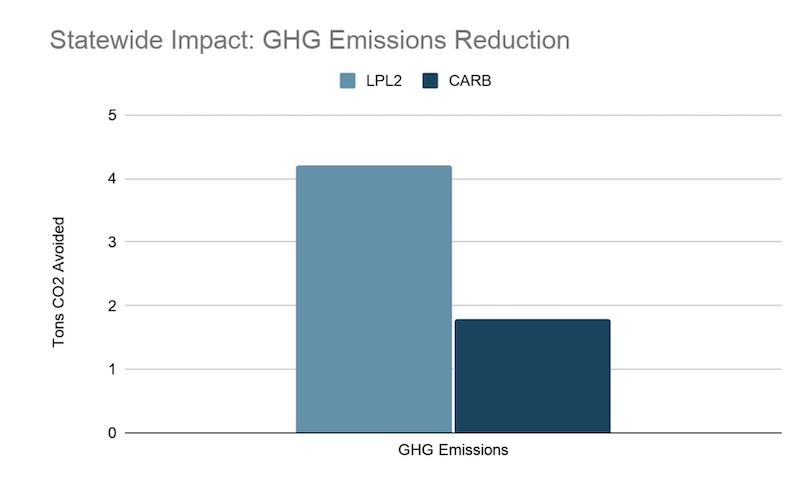

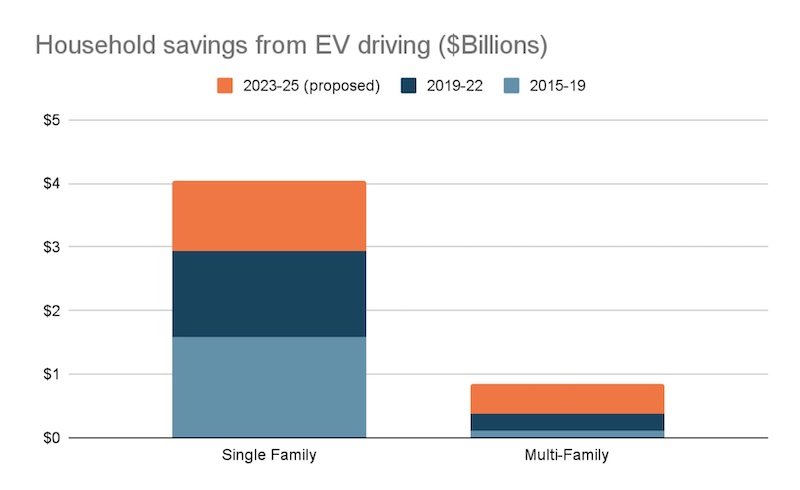

Providing access to EV charging for all new California Multi-Family Housing units enables significant cost savings — both to the families living in the approximately 150,000 new MFH units projected to be built during the three-year (2023-2025) code cycle, and to California as a whole. One member of the coalition conducted a preliminary cost/benefit analysis which estimated the cost of providing access to power to be $1,366 per receptacle, or between 0.2 – 0.7% of a typical new MFH unit’s construction cost. The analysis showed that this (small) upfront investment would provide $1.1 billion in direct savings for those that live in new Multifamily Housing, while avoiding 4.2 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions. It also showed that, by providing access to power at the time of construction, the state would avoid $1.6 billion in utility retrofit costs. (Actual benefits would be significantly higher, as these estimated cost savings do not take into account the avoided health, economic, and climate costs from carbon emissions and local air pollution.)

Figure 5 – The Coalition’s proposal (“LPL2”) results in much greater reductions in Greenhouse Gas Emissions than the proposal from California’s Air Resources Board (“CARB”)

Figure 5 – The Coalition’s proposal (“LPL2”) results in much greater reductions in Greenhouse Gas Emissions than the proposal from California’s Air Resources Board (“CARB”)

Fig. 6 – Savings from EV driving, based on existing CALGreen building code, disproportionately goes to Single Family Home residents.

Fig. 6 – Savings from EV driving, based on existing CALGreen building code, disproportionately goes to Single Family Home residents.

The coalition shared these findings with the code-writing agencies, and encouraged them to incorporate holistic and systemic cost reductions into their analyses of any proposed EV-related code changes. This was one of many tactics the coalition employed to influence the code-making process, which included:

- Educational webinars for coalition members on EV charging and the code-making process

- Participation in public stakeholder meetings

- Submission of cost/benefit analyses of the draft proposals

- Submission of formal sign-on letters after each public meeting

- Private meetings with staffers and other stakeholders

- Coordination with state legislators (who subsequently sent their own letters to the agencies, echoing the coalition’s demands)

- Coordination with the California Democratic Party, leading to a priority resolution calling for access to EV charging for Multifamily Housing in the party’s 2021 platform

- Coordination of public comments during the current 45-day comment period

While all but the last of these efforts happened in the ten months prior to the first (and only) ‘public comment period,’ agency staff repeatedly informed the coalition that its efforts were ‘late in the process.’ It seems that the code-making process begins immediately after any given cycle is complete, and meaningful influence needs to happen from the very beginning in order to be most effective.

Special Interest Influence – Triangulating between the for-profit building industry and the for-profit EV industry

As Dr. Leah Stokes points out in her recent award-winning book Short-Circuiting Policy, “the public rarely pays attention” in highly technical policy arenas. The coalition found this to be notably true of the code-writing process for EV infrastructure in California. The agencies’ public hearings, held remotely via Zoom due to pandemic protocols, were structured as small ‘stakeholder meetings’ – during which it became clear that they were not used to robust public participation. It also became clear that the chief lobbyist for the building industry and the apartment owners association, who refers to himself as an ‘engineer’ and ‘technical director’ is a long-time, close ally to the agency staffers. This lobbyist also has a leadership role on the Building Standards Commission’s Green Code Advisory Committee, which is charged with reviewing residential code recommendations put forward by the Housing and Community Development agency.

Additionally, in conversations with staff and policy makers responsible for developing CALGreen, the coalition found that these decision-makers often lacked direct experience with EVs, let alone charging technology. Many also lacked lived experience as residents of multi-family housing — which may help to explain CALGreen’s overt focus on owner-occupied single family homes. While EVs have been in California since the late 1990s, adoption has been relatively slow until recently; in 2020, EVs accounted for just under 8% of registered vehicles.

Lack of experience with this technology on the part of policy makers serves to increase their risk of influence by industry lobbyists. “Interest groups are able to control policy in these kinds of domains because legislators defer to interest groups, believing they hold greater expertise,” writes Stokes, citing research by Pepper Culpepper. “Over time, lobbyists build strong relationships with legislators and their staff, providing them with information,” she writes, “[and] lobbyists sometimes become de facto additional staff members for legislators.” Notably, Stokes also argues that “interest groups are more likely to dominate in regulatory bodies because these venues are invisible to the public” (emphasis ours). The regulatory bodies charged with creating CALGreen appear not to be immune from this tendency.

While the building industry has the longest history of influence in California’s code-making process, additional for-profit special interests weighed in during this code cycle, including automakers, public and investor-owned utilities (IOUs), and the burgeoning Electric Vehicle Service Provider (EVSP) industry. (During the 2022 cycle, IOUs chose to keep their direct advocacy ‘quiet’ — attending public meetings but not making public comments.)

Fig. 7 – Tesla charging at a Level 1 receptacle.

Fig. 7 – Tesla charging at a Level 1 receptacle.

The coalition sought to work with the EV industry, with some success. The biggest point of difference was on the amount of power to be delivered at parking spaces. Tesla, the only automaker that manufactures vehicles (electric or otherwise) at scale in California, has a policy of never advocating for Level 1 charging (i.e. 1.4-1.9kW, delivered via a standard 3-prong 110/120v receptacle on a 15 or 20A circuit) — despite it being widely known that Tesla owners (like all plug-in car owners) often charge on Level 1 at home. Similar to the Alliance for Automotive Innovation (which represents all other major automakers in the EV space), Tesla typically advocates for a minimum of “full Level 2” (i.e. 6.6 – 7.6 kW, delivered via 208/240v on a 40A circuit). A compromise was reached within the coalition to advocate for a minimum “floor” of 3.3 kW via 208/240v on a 20A circuit, also known as “low power level 2,” with an option to use Automated Load Management Systems (ALMS). (See here, here, and here for examples of third party ALMS systems.)

Updated CALGreen Proposal: Significant, but not Sufficient

As a result of the coalition’s efforts, HCD in March came back with a revised draft proposal, doubling the amount of mandated EV infrastructure from 20% to 40% of new spaces – but only for buildings over ten units. While the participating EV industry representatives were pleased with this result, the EV Charging Access for All coalition’s leadership recognized that the new code proposal, while an improvement, was still far from equitable. The draft proposal still mandated EV Capable rather than ‘plug and play’ EV ready; left out all MFH sites with under ten units; used parking spaces rather than housing units as a basis for assessment; did not include signage; and – depending on the ratio of MFH units to parking spaces – had the potential to leave up to 60% of multifamily residents in new buildings completely without access to power for EV charging. Ironically, the new proposal mandated higher power than the coalition had requested.

In response to the March HCD proposal, the coalition (this time without the support of Tesla or the other EV industry coalition members) proposed a compromise with HCD for the 2022 cycle: to include, in addition to the code proposed by HCD, an alternative compliance pathway (ACP) within CALGreen. The coalition’s proposed ACP was less prescriptive for builders, while ensuring that 100% of units had access to EV charging but at a lower average power level. In April, 2021, as part of the formal code development process, the Green Code Advisory Committee (CAC) reviewed HCD’s proposal and the coalition’s suggested ACP, and recommended that HCD explore adding the ACP to its final proposal.

HCD staff immediately informed the coalition that they did not intend to comply with the CAC’s recommendation. Since then, however, the coalition has learned that the agencies have “made significant edits to the proposed EV regulations based on the April 2021 GREEN Code Advisory Committee (CAC) recommendations and public testimony,” but that “the revised CALGreen regulations do not contain [the coalition’s] requested ACP.”

Conclusions and Next Steps

In the ongoing effort to advance light duty vehicle electrification, there has been a significant lack of attention to building codes as a means to increase and democratize access to EV driving. Our experience advocating for improvements to CALGreen in California indicate that this is an area ripe with possibility for rapid improvement. Building codes that ensure all new residential construction includes access to power for EVs serve to avoid the expensive process of retrofitting, and provide a basis for equitable future access to EV charging. Work focusing on building codes for EV infrastructure needs to continue in California, and should extend to other US states as quickly as possible.

Note: The 2022 CALGreen cycle will be completed by January 1, 2022, and a final analysis of EV Infrastructure in this code cycle will be available online at acterra.org.

Vanessa Warheit, Acterra

Vanessa currently co-leads EV Charging Access for All — a coalition of over a thousand organizations, companies, faith communities and individuals advocating for equitable access to affordable electric vehicle charging infrastructure. She was formerly Executive Director of Fossil Free California, and California Organizer with 350.org of Rise for Climate Jobs & Justice. Vanessa holds a masters degree in Communication from Stanford University; she produced the PBS documentary The Insular Empire, and the award-winning kids video Worse Than Poop!

Andrea Marpillero-Colomina, GreenLatinos

Andrea researches the intersections of people, policy, and place. She is currently the clean transportation advocate at GreenLatinos and faculty at The New School, where she teaches undergraduates at Parsons School of Design and Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts.

Marc Geller

Marc has been driving electric cars since 2001. He has driven over 250,000 electric miles, including two cross-country trips. He is the Vice President of Plug In America and on the Board of Directors of the Electric Vehicle Association and AdoptaCharger. He appears, briefly, teary-eyed, in the 2006 documentary “Who Killed the Electric Car?” He writes and agitates for transportation electrification.

Sven Thesen

Sven is a chemical engineer and founder of Project Green Home and Sven Thesen & Associates, a boutique consulting firm focused on the economic and environmental impacts of electric vehicles. He has demonstrated vehicle-to-grid technology, the secondary use of transportation batteries in the stationary sector, and intelligent charging with Pacific Gas & Electric, Tesla, Better Place, and Peninsula Clean Energy, among others.