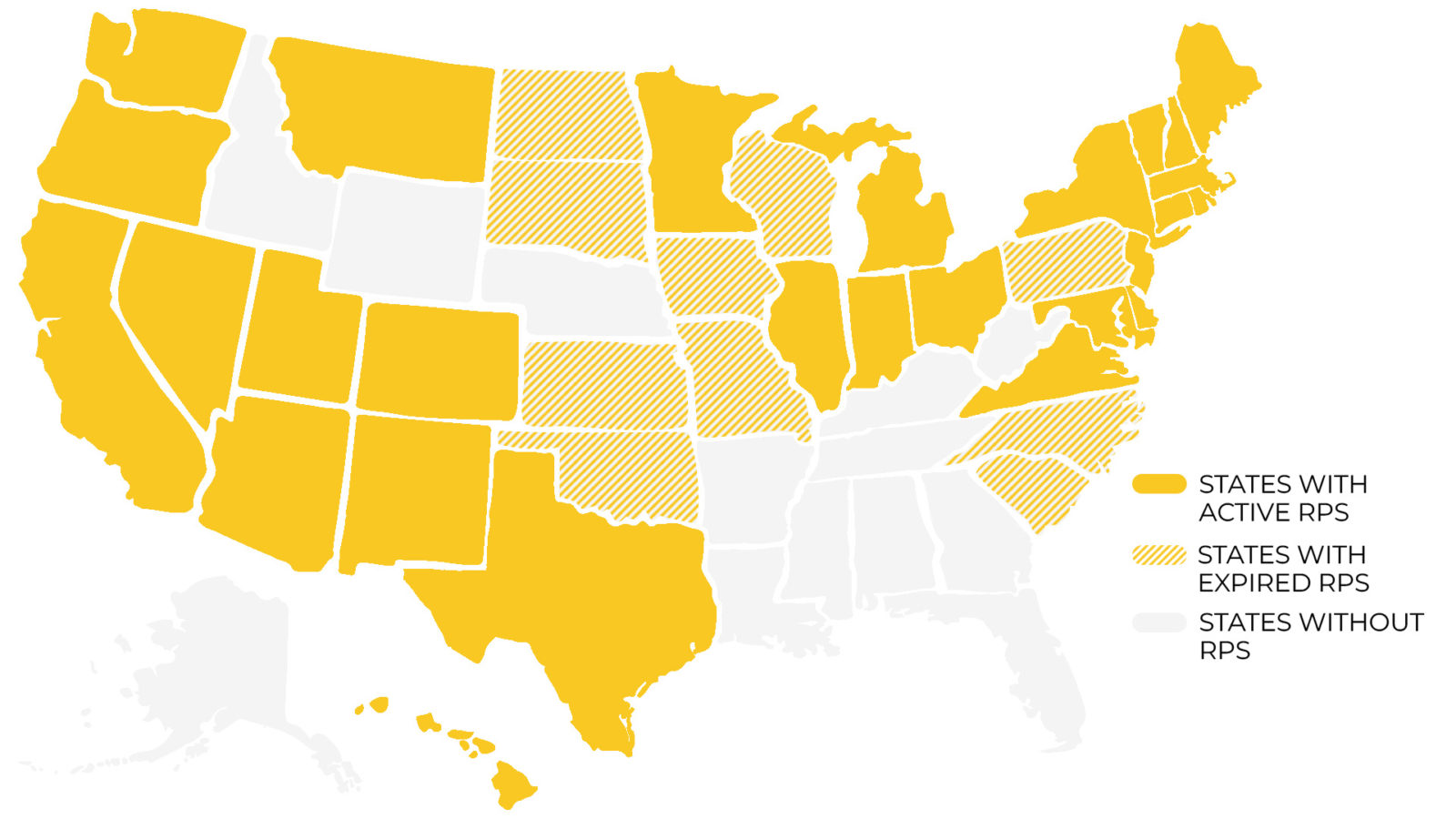

Climate XChange’s Dashboard Digest is a deep dive on each of the policies that we track in the State Climate Policy Dashboard and an exploration of how these policies can interact with one another to form a robust policy landscape. The series is intended to serve as a resource to state policy actors who are seeking to increase their understanding of climate policies, learn from experts in each policy area, and view examples of states that have passed model policies. We’re beginning our series by exploring renewable energy and energy storage policies.

Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) policies create a roadmap for the future of renewable energy development in states. This key market creation policy builds on other energy policies in a National Renewable Energy Laboratory framework known as policy stacking. The idea is that policies that seek to grow renewable markets are more effective when they are supported by earlier foundational ones.

RPSs are mandates for utilities to provide increasing amounts of renewable energy to their customers. Having a strong RPS means that a state can create demand for renewable energy, causing generators to increase the supply. The state signals that it is committed to expanding this industry and encourages investors to buy in.

This article is a part of our Dashboard Digest series and examines what RPSs are, how they can be effective, and how they differ from state to state.

Read more about policy stacking in our previous Dashboard Digest article: Unlocking Renewable Energy Potential through Policy Stacking

Overall State Policy Coverage

An Early Renewable Energy Policy

In the 1970’s, the United States was consuming increasing amounts of oil, while our petroleum production was decreasing and our imports growing. This meant that when oil embargoes were placed on the United States in 1973, energy prices skyrocketed and there was a demand for domestic alternatives. At the time, the country’s other options, coal and uranium, were expensive and the winds were shifting in another direction: renewable energy. This push to decrease reliance on foreign fossil fuels contributed to the development of renewable energy technologies, like solar and wind, as well as nuclear power.

Iowa, a state that for many people conjures images of open skies and rolling fields of corn, was once a national leader in renewable energy policy. In 1983, Iowa became the first state to pass an RPS law, which required utilities to procure a certain amount of their electricity sales from renewable sources, or what they referred to as “alternate energy production facilities.” This law led the way for Iowa, which was at the time an energy-poor state, to become the second largest producer of wind energy in the country today. There are a lot of contributing factors to this transition, but it began with lofty goals that crossed party lines.

Prior to Iowa’s RPS, commercial wind power was largely limited to California because of substantial federal and state tax incentives for renewable energy. State lawmakers in Iowa observed what was happening on the west coast, and posed a novel question: Why couldn’t Iowa do the same?

Iowa State Representative David Osterberg, a progressive politician and one of the law’s sponsors, explained that an RPS could both conserve finite fossil fuel resources as well as increase the reliability of the state’s electric grid. He told the Cedar Rapids Gazette, “Having a mix of alternate energy production facilities would help determine how reliable the various types are and balance each other out.”

So what exactly did this new type of law do? The main component of Iowa’s RPS was that the state’s two utilities were required to procure 105 megawatts of renewable energy. This first iteration of an RPS was simple, but it was still a groundbreaking bipartisan effort at regulating utilities to incorporate renewable energy into a state’s portfolio.

Iowa has had a lot of success resulting from their efforts – today wind power accounts for more than 55 percent of the state’s net electricity generation. Interestingly, however, the state didn’t see a substantial increase in their wind generation until the turn of the 21st century. More than anything, this illustrates that renewable energy market development can be the result of complex and intersecting policies. Iowa’s RPS lacked enforcement mechanisms and had a relatively low renewable energy requirement. Other policies, like net metering and interconnection, as well as more favorable economic trends have enabled Iowa’s wind energy industry to grow to where it is today.

Iowa’s RPS was called the Alternate Energy Production Law

These facilities included: solar, wind turbine, waste management, resource recovery, refuse-derived fuel, or woodburning facility

What are Modern Renewable Portfolio Standards?

RPS policies set mandatory targets for utilities to procure renewable energy for their customers while also supporting a more resilient electric grid. They diversify a state’s energy portfolio, much like a retirement planner diversifies their client’s investment portfolio. One of the goals is to promote long-term electric grid reliability while protecting the state from problems that arise in the future. If a state generates most, or all, of its electricity from one resource, it could be at risk if that resource’s supply diminishes or if there are global price shocks or fluctuations.

These policies differ greatly from state to state based on different objectives, resources, and political environments. Though no two state RPSs are exactly the same, they all share a similar structure: an RPS requires a state’s utilities to provide a percentage of their overall electricity sales from renewable, or carbon-free, resources by a specific date, often with intermediate targets along the way.

These requirements place some of the burden of transitioning a state’s electricity system onto utilities, while giving them a timeline to prepare for the transition. The state sets a target that a utility must meet, and then utilities are given varying levels of freedom to decide how they’ll accomplish the goal (some utilities are required to create a plan to meet their targets). An RPS will also specify which utilities are affected by the requirements, and may have different targets for different utility classes. For example, Investor-owned utilities may have stricter requirements than a municipal utility or rural electricity cooperative.

Investor-owned utilities are for-profit electric distributors that issue stock owned by shareholders.

Depending on a state’s history, available resources, and renewable energy goals, RPSs define which technologies are eligible to satisfy the requirements of the law. Some states have slightly different energy procurement laws known as Clean Energy Standards (CES). This type of law functions much the same as an RPS, with the main difference being that they allow for non-renewable, zero-carbon energy sources such as nuclear power. Either way, both RPS and CES policies share the same goal of diversifying a state’s energy portfolio while expanding alternative energy development.

In addition to mandating renewable energy procurement, RPSs also have a market-based component. In most cases, a utility earns a Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) when they produce or purchase a certain amount of eligible renewable energy, commonly one megawatt of power. Because each certificate is unique, they function as a way for regulators to track where renewable energy is being produced and whether or not a utility is meeting their requirements. Also, RECs can usually be sold to other utilities that may be falling short of meeting their own requirements. We’ll cover Renewable Energy Certificates more closely in a future article, which will explore how these systems are set up, and how they can cause problems for a state’s renewable market.

Read more: Clean Energy 101: The REC Market

Creating an Energy Market with Renewable Portfolio Standards

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory framework of policy stacking sorts renewable energy policies into tiers related to how they affect market development. The first tier of policies includes ones that prepare a market for renewable investment. These foundational policies, such as net metering and interconnection standards, reduce or remove physical, financial, or bureaucratic barriers to installing renewable energy. Second tier policies actually create a market and increase demand for renewable energy. The third and final tier of policies expand an existing market into niches that are left behind by normal economic forces. These policies include financial incentives for renewable energy technologies.

RPSs are key to the second tier in the policy stacking matrix: market creation. When a state requires utilities to procure a certain amount of renewable energy, it has several impacts on the state’s renewable energy market. First, this requirement manufactures long-term demand for renewable energy. A utility’s demand for renewables rises because they have a legal and punishable obligation to acquire it. In response to all this demand, energy producers are expected to increase their supply of renewable energy.

An RPS also signals stability to potential investors. By assuring investors that there will be long-term local demand for renewable energy, an RPS makes a state’s market more attractive. Generally, investors love certainty, and an RPS helps make the market feel predictable and safe to invest in.

Because RPSs are a market creation policy, they are made more effective when tier one policies have reduced other barriers to renewable energy projects. An ambitious RPS is tough to meet without strong foundational policies that have adequately prepared the state for a mature renewable market.

Read more: Learn more about net metering policies in our Dashboard Digest article

What Makes Renewable Portfolio Standards Effective?

RPSs are an important policy for decarbonizing energy systems, but they are part of a complex system of interacting policies. The following list of recommendations, adapted from the State Policy Opportunity Tracker (SPOT), are non-exhaustive and don’t necessarily lead to increased renewable energy development, but are strengths shared by ambitious RPS policies.

Renewable energy targets should be set as high and as soon as possible, with interim targets. This one is key to effective RPSs: states must decarbonize their electricity sectors as quickly as possible. Research from the most recent IPCC report suggests that in scenarios that lead to the least amount of global warming, the electricity sector must be one of the first to decarbonize. It’s important that RPSs are mandatory, enforceable, and ambitious with their percentages and dates. By doing so, states can have greater chances of meeting the ambitious goals to limit the effects of climate change.

Eligible technologies should advance clean energy development while respecting different state contexts. One reason why no two RPSs are identical is that different states have different goals based on existing resources, geographic constraints, and political environments. It may make sense for one state to give more weight to one type of technology that it’s seeking to expand, whereas another state may have more development and not as much demand.

RPSs should apply to all electricity providers: investor-owned, publicly-owned, and cooperatives. All electric utilities should be required to procure additional renewable energy. Some RPSs may specify different targets based on utility type and number of customers, but what’s important is that the RPS leads to a cleaner state-wide energy grid.

There should be clear annual reporting procedures to prove utilities are meeting their requirements. Utilities should have systems that monitor their compliance with the RPS and penalties for failing to meet requirements that are strong enough to encourage compliance.

Some utilities may benefit from requiring plans for procuring renewable energy. While an RPS mandates that a utility must procure renewable energy, it doesn’t on its own guarantee that it will happen. It’s still possible for a utility to fail to comply with their requirements, even with enforcement mechanisms like fines. When an RPS requires utilities to propose plans for how they will procure the required energy, states can be more confident that it will actually happen.

A system that issues, records, and tracks Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) should be implemented. There should be a system for how RECs are created, tracks where they end up, and is transparent and publicly accessible.

Provisions should be established that designate energy requirements for distributed generation or specific desired technologies. Left to their own devices, utilities will often make decisions that increase their own revenue. In practice, this often results in point-source generation facilities such as large wind or solar farms. While these projects have benefits of economies of scale and total capacity, grids can be made more resilient by promoting distributed energy generation. Effective RPSs will require a portion of the overall energy to be procured from these smaller facilities or even individual customers with net metered power generation.

Distributed generation is electricity that is produced at or near the site where it will be used. Examples include rooftop solar, small-scale wind, and combined heat and power systems.

State Examples

Washington

In 2019, Washington passed the Clean Energy Transformation Act (CETA) which had a lot of components, one of which was an updated RPS. The law was passed in the state legislature almost entirely down party lines, with partisanship that was not present with the state’s original RPS which was passed by ballot initiative in 2006 with support from both sides of the aisle. Previously, Washington’s RPS required only 15 percent renewable power by 2020. The new law set three mandatory targets for the state:

- End coal generation by 2025

- 100 percent carbon neutral power by 2030

- 100 percent carbon-free power by 2045

CETA’s requirements allow for non-emitting electric generation which includes nuclear power, natural gas with carbon capture and sequestration, and other sources that have no greenhouse gas emissions.

The law also includes a unique component that both gives utilities some latitude and promotes other decarbonization projects. Only 80 percent of the 2030 goal has to be met with clean energy generation. Utilities have some freedom with the other 20 percent: they can purchase RECs from other utilities, pay a penalty for not meeting their requirements, or invest in what the state calls “Energy Transformation Projects”. These are projects that would reduce fossil fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions while providing other benefits to a utility’s customers such as electric vehicle infrastructure and weatherization. This option incentivizes other beneficial projects and gives utilities some leeway if they’re having trouble meeting their clean energy requirements.

Lawmakers included a cost cap in the bill to win favor of the state’s utilities. This rolling cap assures utilities that their expenses associated with meeting the clean energy requirement couldn’t exceed two percent of the previous year’s electricity sales. Having a cap like this doesn’t get a utility out of complying with the law, but it can potentially elongate the timeline.

Read the bill: Clean Energy Transformation Act

The new RPS applies to all electricity providers in the state and requires that they develop short- and long-term procurement plans to meet the standards at the lowest possible cost. Additionally, utilities must assess the impacts of their plans on two community types: vulnerable populations and highly impacted communities.

Colorado

Colorado was the first state to pass an RPS by ballot initiative, doing so in 2004. The original RPS required electricity to be generated by eligible sources, but different utility types had varying requirements:

- Investor-owned utilities: 30 percent renewable energy by 2020

- Electric cooperatives serving 100,000 customers or more: 20 percent by 2020

- Electric cooperatives serving less than 100,000 customers and publicly-owned utilities serving more than 40,000 customers: 10 percent by 2020

While Colorado’s original RPS was not the strongest, the state’s largest utility made an ambitious announcement in 2018, two years before their deadline. XCel Energy, an investor-owned utility that operates in several states, announced company-wide goals that exceeded their legal requirements by a lot. The company declared that they would provide 80 percent renewable energy by 2030 and would be carbon free by 2050.

To be sure, these were voluntary targets, but it is notable that the push was led by a utility company – something not seen very often. This signaled that XCel Energy was on board with renewable energy and was making a bet on the long term viability of the market in the state. By committing to these lofty goals, the company can not only garner public support but is also evidence that renewables are becoming more cost competitive than their fossil fuel counterparts. While there may be a moral component to XCel’s desire to clean up their energy, they wouldn’t have made this move if they didn’t think it would pay off. This illustrates how utility companies are not inherently against climate policy; they are more concerned with the cost and reliability of energy. When those things align, utilities can get on board.

Vulnerable populations: those that experience disproportionate cumulative risk from environmental burdens due to socioeconomic and biological factors.

Highly impacted communities: Highly impacted communities – geographically impacted by fossil fuels and climate change identified by the state Department of Health Environmental Health Disparities Map.

XCel Energy’s announcement may have contributed to the state passing SB 19-263 the following year, which formally updated Colorado’s RPS. There are two goals in the new policy: by 2030 utilities must reduce carbon emissions from electricity by 80 percent of 2005 levels, and must provide 100 percent clean energy by 2050.

This part isn’t actually a traditional RPS requirement because it doesn’t specify renewable procurement, only emissions reduction.

Rhode Island

In 2022, the country’s smallest state passed an RPS with the largest goal of requiring utilities to provide 100 percent renewable power by 2033, sooner than any other state’s commitment. The law includes a structured schedule of increasing percentages each year, to make the overall target more attainable while ensuring utilities can’t put off their requirements.

In 2020, renewable sources contributed around 10 percent of Rhode Island’s electricity consumption, but the state is on its way to reaching the target. In June 2022, the state legislature passed a bill that would require the state’s main electric utility to procure at least 600 megawatts of newly-developed offshore wind energy. The bill is now waiting for the signature of Rhode Island’s governor, who, because he pushed for its introduction, is expected to sign it.

About CNEE: The Center for the New Energy Economy was founded in 2011 as a department at Colorado State University by Colorado’s 41st Governor, Bill Ritter Jr. The Center convenes and facilitates dialogue among policymakers and stakeholders, connects energy policy leaders and experts, creates and maintains free, publicly available tools and resources, and publishes energy policy research.

About The State Policy Opportunity Tracker (SPOT) for Clean Energy: The SPOT for Clean Energy is a hub of information on state-level clean energy policy. Intended as a planning aid, the SPOT for Clean Energy aims to inform decision-making by providing policymakers, regulators, and interested stakeholders a clear snapshot of existing state policies and opportunities for future policy adoption.