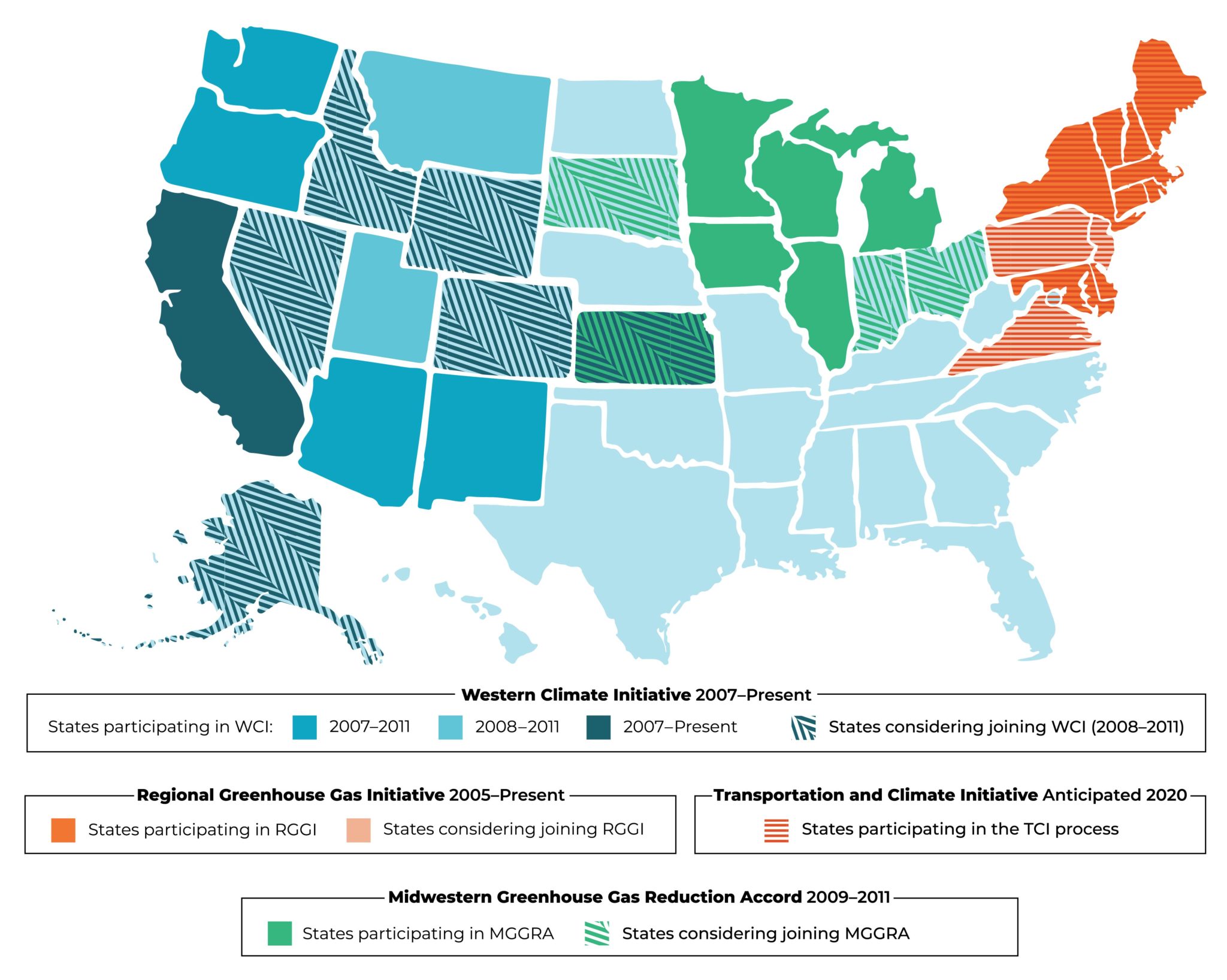

With COP25 currently underway, market-based approaches to emissions reductions have been a major topic of negotiations among almost 200 countries, as they work to finalize rules under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. On November 4th, the United States formally started the process to withdraw from the Paris Agreement — after President Trump announced his intention to do so back in 2017. Representatives from the United States still attended the conference in Madrid, Spain — and will continue to be at future COP meetings — but starting in 2020, the country won’t be participating in formal negotiations. The administration has been widely criticized, as it has resigned the U.S.’s leading role in international climate negotiations and ambition.

Looking back a decade ago, however, the country appeared to be leading the way to strong climate policy. More than half of U.S. states were working to develop regional initiatives to establish market-based programs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It might now seem shocking that states like Wyoming and Ohio — where fossil fuel production remains a key part of the state’s economy — were involved in these initiatives, but at the time, reducing emissions was widely recognized as dire, and necessary.

In the late 2000’s, states were anticipating that a national cap-and-trade program would eventually become a reality, and their ambition to move forward immediately remained high. However, on the heels of the Waxman-Markey failure in 2009, the Great Recession, and state elections, regional efforts soon started to collapse as well. So, what happened over the course of the past 15 years? Why did regional carbon pricing agreements fall apart, and how did 30 states looking to implement carbon pricing diminish to just ten following through a decade later? Crucially, can states make up for lost time and rapidly reduce emissions, despite federal inaction today?

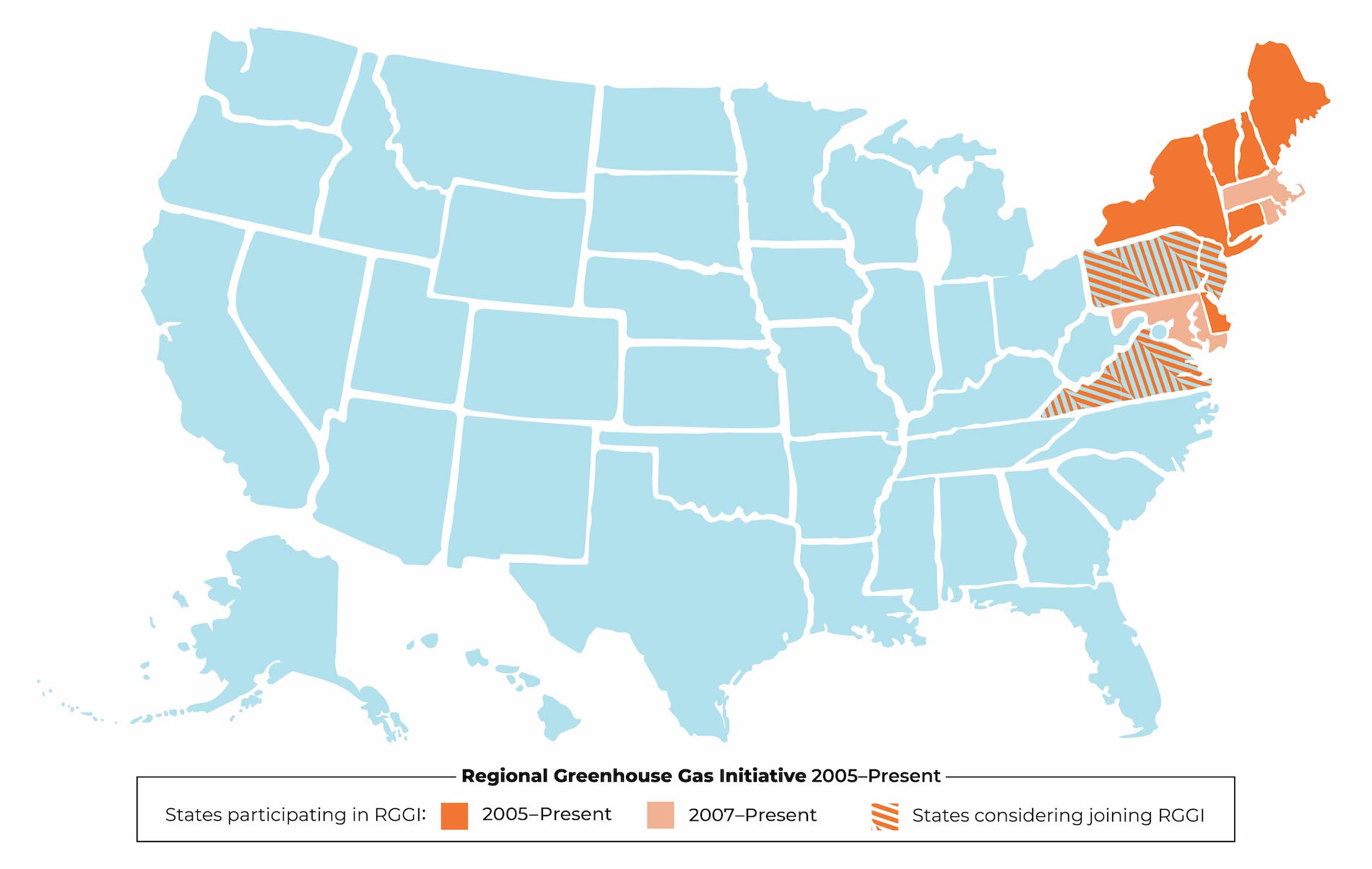

Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) was the first mandatory cap-and-trade program in the U.S. intended to reduce emissions in the electricity sector. In the absence of federal regulations, former New York Governor George Pataki issued a call to other governors in the region to design a mandatory program to limit emissions from the electric sector in 2003. On December 20th, 2005, the governors of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Vermont announced an agreement to implement RGGI, outlined in a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). In 2007, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island joined the initiative by signing the MOU.

The program was designed so that individual states needed to enact legislation or regulations based on the RGGI model rule, released in 2006, to establish individual CO2 Budget Trading Programs. These programs limit carbon dioxide emissions, issue allowances, and establish participation in regional auctions for allowances. The first multistate auctions occurred in September and December of 2008, and the first compliance period began on January 1, 2009.

The original cap was set to approximately 188 million tons of carbon dioxide for the entire region and was designed to decline by 2.5% annually between 2015 and 2018 — aiming to achieve a 10% reduction in emissions from power plants by 2019. The states originally planned to give away the allowances to generators, who could then trade them, following Europe’s Emissions Trading Plan. But advocacy by a coalition of environmental groups convinced the states that selling the allowances and using the funds for clean energy and other state programs made more sense.

As a result, states were required to sell at least 25% of permits by RGGI guidelines (yet almost every participating state sells all their permits); auction revenue is mostly used to invest in energy efficiency programs, and a small percentage is rebated back to consumers and businesses.

What’s going on now?

RGGI is the longest-operating cap-and-trade program for carbon dioxide in the United States – in 2017, RGGI states agreed to extend the program through 2030, and the cap will be readjusted again to account for banked allowances. The program sets an annual cap on the region’s emissions from the electric sector, which currently declines by 2.5% annually through 2020. In 2019, the adjusted cap decreased to 58.47 million tons of CO2 — approximately a 30% decrease in the program’s initial cap in 2009.

The first auction — with only six states — raised $38.5 million, and the second raised $106.5 million. By July 2019, the program had raised $3.2 billion. Over 80% of auction revenue has been invested in energy efficiency programs and other measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, which accounts for just over 10 percent of government-mandated spending on efficiency in the RGGI region. Emissions from the electricity sector in the region have dropped by approximately 47% since 2008, although the majority of these reductions have been attributed to factors other than RGGI, and electricity prices have fallen almost 6%. Studies show the program has generated almost $6 billion in co-benefits.

More states could be joining RGGI

2019 marked an exciting year for RGGI. The regional program gained New Jersey, starting in 2020, and two other states are expected to join in the coming years. Virginia — which could have joined in 2020 with New Jersey — is expected to start participating in 2021, and Governor Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania announced the state’s entrance in a recent executive order. Despite pushback from the Republican-controlled legislature, Pennsylvania is expected to join RGGI starting in 2022.

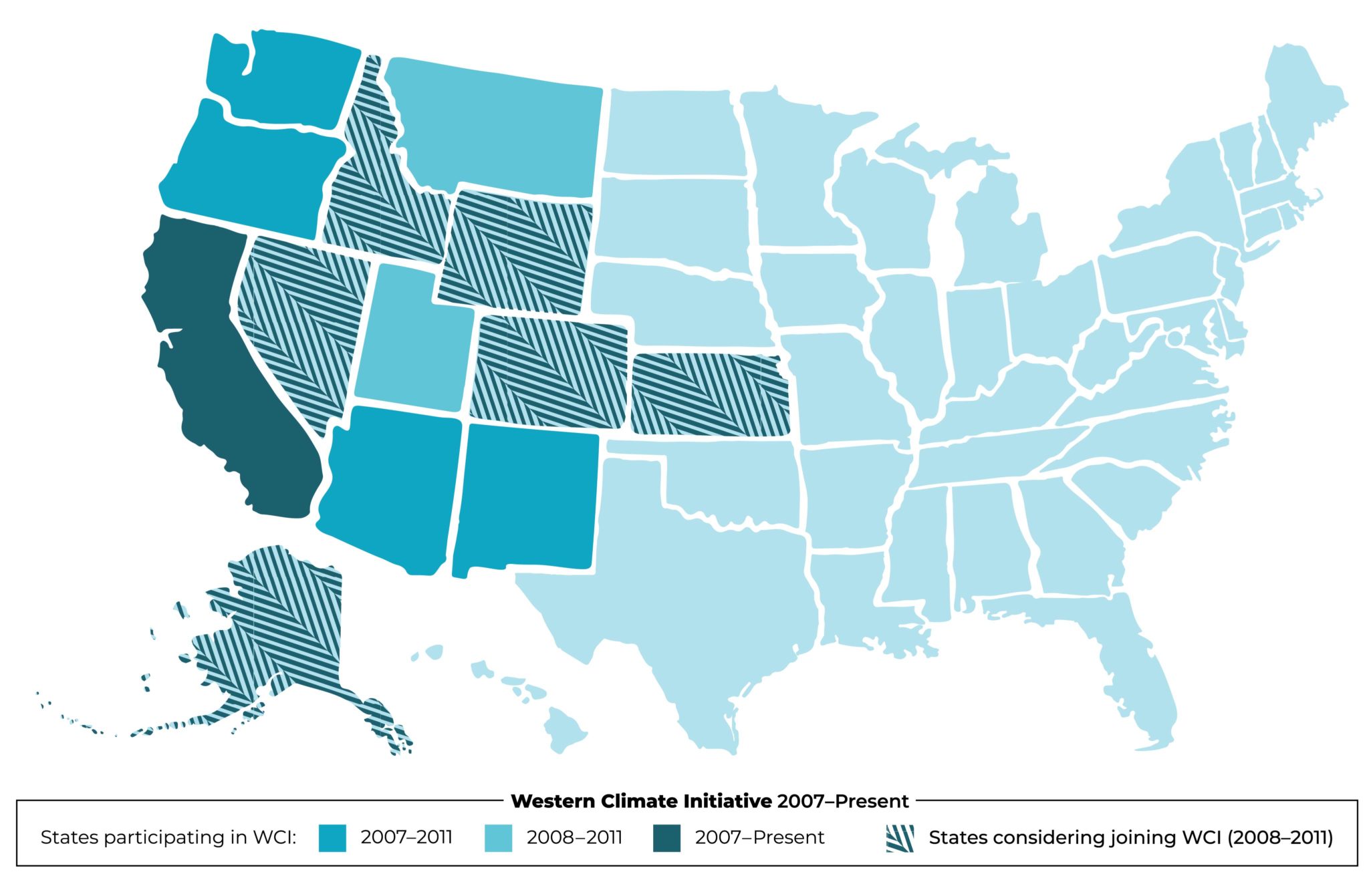

Western Climate Initiative

The Western Climate Initiative (WCI) was created in February 2007, when the governors of Arizona, California, New Mexico, Oregon, and Washington signed the Western Regional Climate Action Initiative. By July 2008, Montana and Utah joined the initiative, as well as the Canadian provinces British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario and Québec. Additional observers included Alaska, Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, Colorado, and Kansas; the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, and the Mexican states Baja California, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, Sonora, and Tamaulipas.

The initiative aimed to collectively reduce regional emissions to 15% below 2005 levels by 2020, with a regional, economy-wide cap-and-trade program as the centerpiece. The WCI also requires that states adopt GHG emission reduction targets, and implement an action plan with complementary policies to achieve these goals. States were also required to adopt California’s vehicle greenhouse gas emissions standards, and they must be a part of the Climate Registry, an organization that helps to measure and report greenhouse gas emissions.

Final design recommendations for the program set the implementation date by January 1, 2012. The first compliance period, beginning in 2012, was designed to regulate emissions from electricity generation, including emissions from electricity generated outside of WCI states but serving WCI region customers; emissions from combustion at commercial and industrial facilities, and emissions from industrial processing facilities. The second compliance period began in 2015, to regulate emissions combusted at residential, commercial and industrial facilities, including in the transportation sector.

What happened to the WCI?

If every state had remained a member of the WCI, the program would have covered about 90% of the region’s greenhouse gas emissions upon full implementation in 2015. However, by November 2011, six states had pulled out of the initiative, leaving California and four Canadian provinces as the only remaining participants. New Mexico, Arizona, Washington, Oregon, Montana, and Utah all formally declined to participate in the WCI. Each state had significant battles to overcome during this process, particularly unsupportive legislatures and changes in state leadership to governors who objected to cap-and-trade. The Great Recession has also been cited as a factor that lowered states’ priorities to address climate change.

California implemented a cap-and-trade program in 2013, making history as the first U.S. state to launch a state-level program, after final regulations for implementation were adopted in 2011. California’s program links with one in Québec, and in 2017, Ontario integrated a cap-and-trade program with the existing WCI partners. However, the province ended the program in July 2018.

Even after the legislature failed to pass any legislation that would authorize emissions trading, cap-and-trade prospects seemed likely in New Mexico. The state became just one of two states participating in the WCI with the authority to implement cap-and-trade; the Environmental Improvement Board (EIB) voted 4-3 to approve a plan to cap emissions from the state’s largest power plants by 3% per year from 2010 levels starting in 2013. The decision also gave New Mexico the ability to trade carbon allowances in the WCI, which only included California at the time. This changed in 2011, when former Governor Susana Martinez — a vocal opponent of cap-and-trade — took office. She formally withdrew New Mexico from the WCI in 2011 and, in 2012, the EIB repealed the emission trading regulations established the year prior.

Although negotiations to establish emissions regulations did not advance far enough in other Western states, they faced similar political obstacles as New Mexico. In Arizona and Utah, voters elected Republican governors who objected to cap-and-trade and withdrew their states from the WCI. Almost every state faced opposition from the legislature as well, and in Montana, Oregon, and Washington, legislatures failed to advance cap-and-trade bills after several attempts. To highlight their resistance to participate, resolutions urging the governor to withdraw from the initiative were introduced in Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, and Utah.

What’s going on in states now?

For the past six years, California’s cap-and-trade program has been a driving force behind the state’s climate goals, playing a key role in achieving its emission reduction goals ahead of schedule. Legislation to extend the program another decade passed in 2017, and set a more ambitious cap — meaning the program will play a bigger role in the state’s emission reduction plans in coming years. To date, the program has generated almost $12 billion in auction proceeds, which is rebated back to residents and over $4 billion of this revenue funds programs that further reduce the state’s greenhouse gas emissions through California Climate Investments. This includes improvements to public transportation; energy efficiency, forest health, sustainable housing, and electric vehicle rebate programs. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) reported that over $2 million has funded projects that benefit disadvantaged communities and low-income households and communities, collectively called priority populations.

However, one of the Trump administration’s recent attempts to dismantle climate policy and stop necessary action focused on California’s cap-and-trade program, claiming that individual states are not able to enter an international agreement. The consequences of this are still waiting to be seen; the program is still expected to continue through 2030, although it might have to delink with Québec.

In the future, WCI might expand to other states in the region. On November 21st, New Mexico announced plans to evaluate market-based programs to cap and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. One day later, Governor Sisolak of Nevada issued an executive order to determine policies and regulations to achieve the state’s emissions reduction goal. Among strategies the administration will consider are “comprehensive economy-wide or sector-specific programs […] including market-based mechanisms,” and will likely include a cap-and-trade program that links with the WCI. State agencies will develop policy recommendations to implement these programs in the coming year.

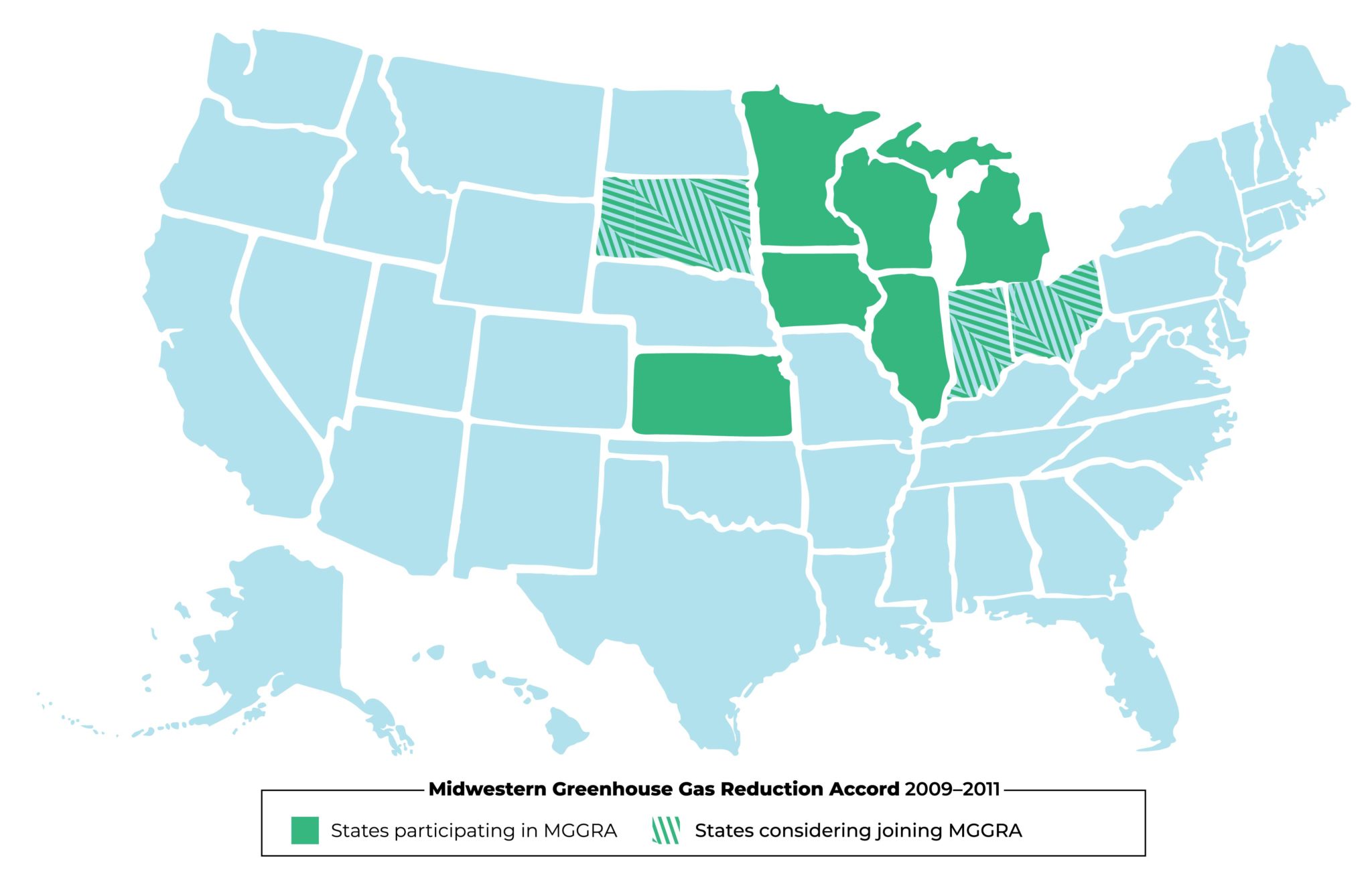

Midwestern Greenhouse Gas Reduction Accord

The Midwestern Greenhouse Gas Reduction Accord (MGGRA) was a regional agreement between Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, and Michigan — as well as the Canadian Province of Manitoba. Indiana, Ohio, and South Dakota were observers of this agreement, but did not participate in planning the regional program. The governors of participating states wanted to reduce their carbon footprints and transition to an economy focusing on energy efficiency, renewable energy use, and greenhouse gas reductions.

In 2009, an Advisory Group presented recommendations to achieve the Accord’s goals, calling for a 20% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 2005 levels by 2020, and an 80 percent reduction by 2050. States agreed to establish greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and develop a regional multisector cap-and-trade system, with the first compliance period starting on January 1, 2012. The program would have covered the electric sector — both electricity generation and imports — as well as transportation fuels, industrial emissions, and fuels used in commercial, industrial and residential buildings. Revenue was to be devoted to the development of new technologies that promote the goals of the program, and for job retraining to promote employment in new industries related to the regions’ emission reductions. Programs to increase renewable energy generation, improve energy efficiency, and deploy carbon capture and storage technology were also included.

What happened?

In a region that has historically been heavily reliant on fossil fuels, the Accord would have made a huge impact. At the time, the Midwest was highly dependent on coal for electricity generation, and had high greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural and industrial sectors in the region. The total greenhouse gas emissions of participating states would have been larger than RGGI or WCI — which still had seven states involved in the MGGRA at the time — and included some of the highest emitting states. The largest emissions reductions would have occurred in the electric sector; with the cap established, electric sector emissions were expected to decrease by 69% by 2030 relative to business-as-usual predictions — an average of 4% per year starting in 2012.

However, progress stopped in 2011 after gubernatorial elections, when all of the governors who signed on to the Accord left office — most were voted out of office or term-limited. Many Midwestern state administrations changed parties; in Kansas, Ohio and Wisconsin, voters elected Republican governors, and as climate change became more of a partisan issue, the shift from Democratic to Republican leadership meant that progress to address climate change and increase clean energy stopped. Negotiations did not advance far enough for states to introduce legislation to implement cap-and-trade or establish greenhouse gas emission reduction targets consistent with the Accord. In fact, resolutions to withdraw from the Accord were introduced in Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota — citing higher costs and job loss as the motivating factors. The agreement has been inactive since early 2011.

What’s next?

The Waxman-Markey bill, which would have created a national cap-and-trade program, never made it to the Senate floor for a vote, and the governors of almost every state involved in regional agreements formally withdrew their participation, with the exception of those in RGGI and California. In 2019, carbon pricing legislation was introduced in 16 states, and that number is expected to continue growing in the coming years. Through executive orders, three more states have committed to joining regional initiatives or exploring market-based mechanisms.

On the East Coast, another regional initiative is in the works. The Transportation and Climate Initiative (TCI) is a regional cap-and-invest program for transportation emissions across 12 Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states. Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. have formally agreed to move forward with a policy to reduce transportation emissions; Maine, New York, and New Hampshire are participating but have not formally signed on yet.

On October 1st, TCI states released a framework for a draft regional policy proposal, which provides an overview and outline of what this program is going to look like. A draft MOU will be released on December 17th of this year (2019), providing more details about what the final policy will look like, and a final MOU will be released in spring 2020 after feedback from stakeholders. After, states will begin to implement the program individually. The cap will be implemented from 2022 to 2032, but the trajectory of the cap has not been determined; advocates are pushing for the cap to be a 40-45% reduction from 1990 levels. Revenue will be invested in low-carbon forms of transportation to further reduce emissions.

Despite the Trump administration’s recent track record, climate action at the federal level is not completely off the table. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi stated the United States is “still in,” since the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement is a decision that moves the United States directly into the wrong direction of progress. To counter this, states are committing to further climate action. Twenty-four governors and the mayor of Washington, D.C. have joined the U.S. Climate Alliance, a coalition of governors committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025 — consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement. However, most states do not have policies in place to meet these targets, and, with only a decade left to drastically reduce emissions, urgent action is necessary.

More than a decade ago, regional carbon pricing agreements signaled the federal government’s failure to enact a national policy to respond to climate change. Although only ten states followed through, there is massive potential for carbon pricing in the future, and states must display that same leadership now.

To stay up-to-date with carbon pricing efforts in states, check out our State Carbon Pricing Network and sign up to our newsletter to get updates weekly in your inbox.