Climate XChange’s Dashboard Digest is a deep dive on each of the policies that we track in the State Climate Policy Dashboard and an exploration of how these policies can interact with one another to form a robust policy landscape. The series is intended to serve as a resource to state policy actors who are seeking to increase their understanding of climate policies, learn from experts in each policy area, and view examples of states that have passed model policies. We’re beginning our series by exploring renewable energy and energy storage policies.

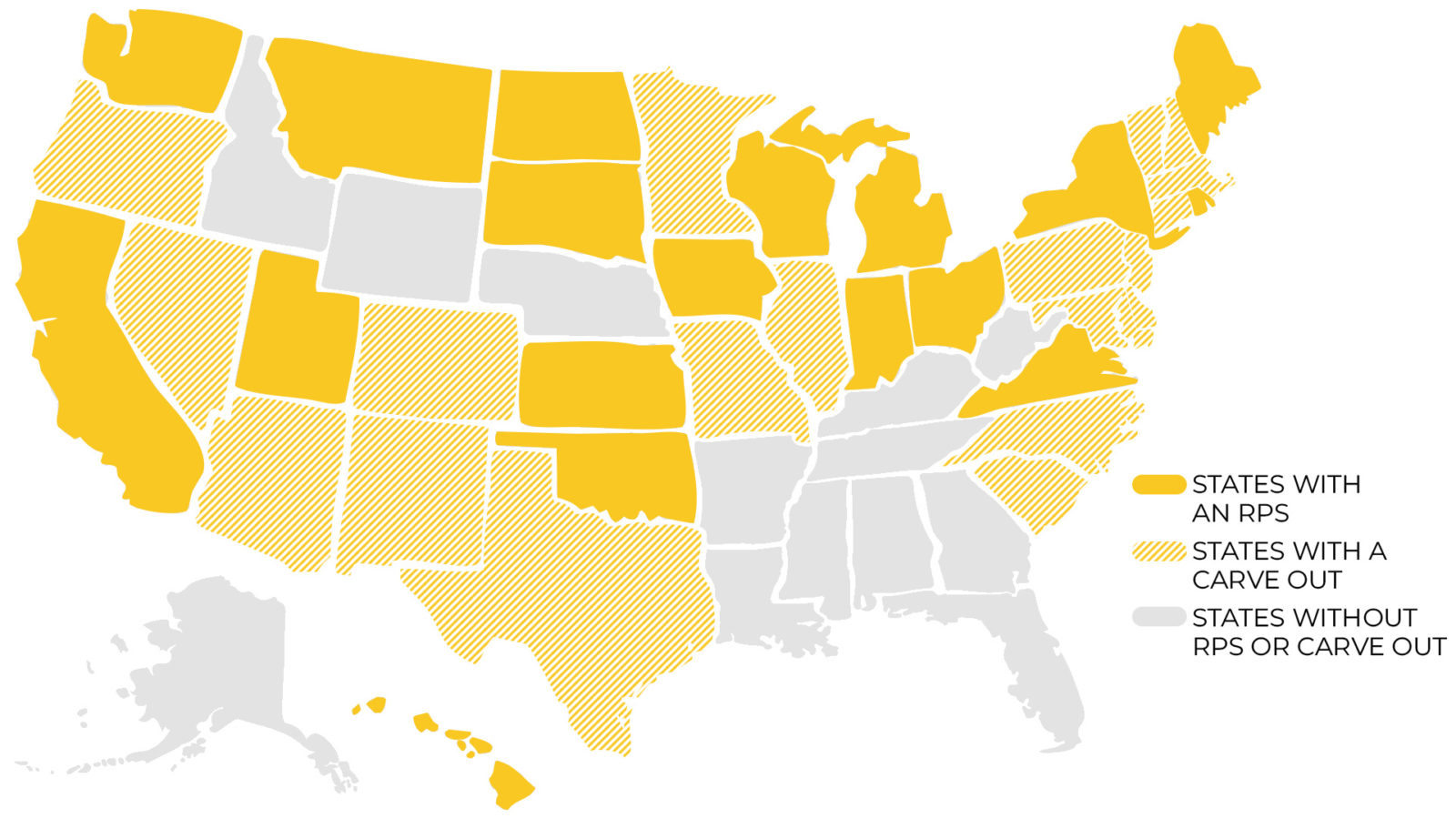

Carve-out policies set aside a portion of a state’s energy goals to help advance certain types of renewable technologies. These policies create renewable markets according to the policy stacking framework from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. The framework theorizes that there is an optimal order in which renewable energy policies should be passed to build on one another.

Read more about policy stacking in our previous Dashboard Digest article: Unlocking Renewable Energy Potential through Policy Stacking

Carve-outs are policies built into a state’s Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) that ensure development of specific renewable technologies. RPSs are a broad policy that requires a state’s utilities to increase the amount of electricity that it gets from renewable sources. Generally, RPSs set a target percentage of the utility’s portfolio that must be renewable by a target date. More ambitious RPS policies have higher percentages and sooner dates. When states include carve-outs in their RPS, they can help spur investment in desired parts of the energy market that may need some help to get started. Carve-outs create demand for specific renewable technologies in a similar way to an RPS, but with a focus on a single energy source.

This article is a part of our Dashboard Digest series and takes a closer look at how carve-out policies work, why states should consider them, and where they’ve already been implemented.

Read more about RPSs in our previous Dashboard Digest article: Creating Demand for Clean Energy with Renewable Portfolio Standards

Overall State Policy Coverage

Maryland’s Early Solar Carve-Out

In 2004, Maryland passed an RPS that required utilities to procure a total of 10 percent renewable energy by 2019. The state wasn’t the first to pass an RPS, but in 2007, they became one of the first to add a solar carve-out provision to the law. This carve-out required electricity suppliers to obtain some of their electricity sales from solar energy in addition to the other required renewables from the RPS law.

The amount of required solar power began small, 0.005 percent of sales in 2008, but was scheduled to increase to two percent by 2020 and was projected to result in 1,250 MW of solar capacity.

Maryland wasn’t done with their carve-out and has made several adjustments to it. By 2010, the state accelerated the solar carve-out timeline for utilities and increased the payments they’d have to make if they didn’t comply. Lawmakers also added solar water heating systems as eligible resources to satisfy the carve-out’s requirement.

Again in 2012, Maryland passed a law amending the state’s solar requirements, speeding up the two percent target date by two years and expanding the eligibility for solar thermal systems.

Finally in 2019, Maryland strengthened their Renewable Portfolio Standards and solar carve-out with the Clean Energy Jobs Act, which raised their required energy mix to 50 percent renewable energy and 14.5 percent solar energy by 2030. While the state doesn’t have the most ambitious overall RPS target, this bill introduced the country’s highest numerical carve-out for solar technology.

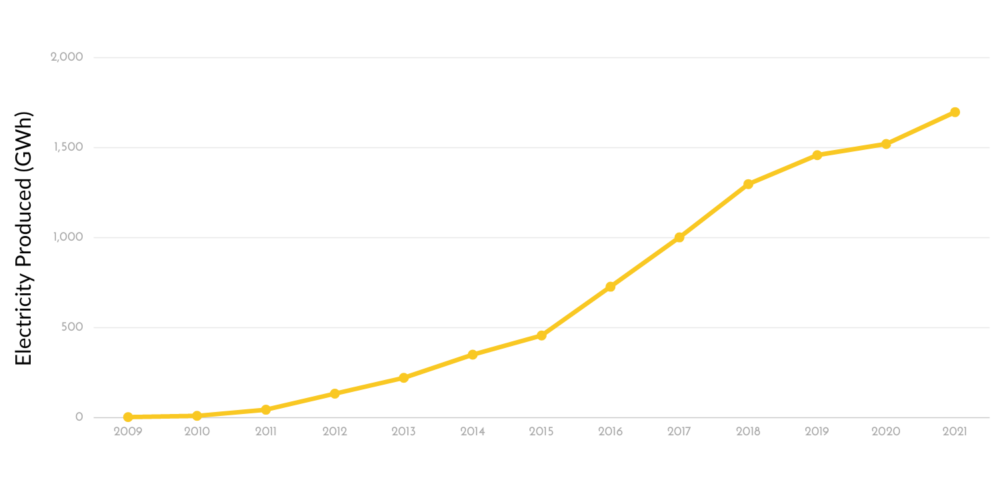

In a testament to Maryland’s solar success, the state has almost quadrupled its solar capacity since 2015, and according to the most recent available data, met its solar-carve out requirement for 2020.

How do Carve-Outs Work?

Renewable Portfolio Standards create demand for renewable energy by requiring a state’s utilities to procure it. Usually the utilities are given a target percentage of their electricity sales that must be generated from clean energy sources by a certain date in the future. An RPS will define which energy technologies are eligible to satisfy the law’s requirements and the lists vary from state to state.

An RPS creates a market for renewable energy as a whole — the state is guaranteeing that utilities will have demand, because unless they wish to pay fines, they’re required to. To help ensure policy effectiveness, penalties should be steep enough so it’s less costly for utilities to comply with the carve-out. These laws also give utilities time to make the transition to a decarbonized energy sector in a structured way. With lists in hand and targets on the calendar, utilities are free to achieve the requirements of the RPS in the most economically advantageous way.

But what if a state wants to advance a certain technology, like rooftop solar power, that isn’t the most affordable renewable energy for utilities? A profit-motivated Investor-Owned Utility may not be interested in supporting renewable technologies that save customers money but cut into utility profits. This is a situation where a state may choose to carve-out a portion of its RPS for that desired technology.

Carve-outs reserve a portion of a state’s RPS that must be satisfied by a specific technology or generation location. In addition to meeting the overall RPS, utilities must satisfy the added requirements of the carve-out. Though carve-outs can generally cover any technology a state wants to increase the demand for, they are most commonly used for distributed generation and solar power. Carve-outs are achieved through three main policy mechanisms: RPS percentages, megawatt procurement targets, and RPS multipliers.

Why Should States Promote Distributed Generation?

Distributed generation is any electricity that is produced at or near the site where it will be used, as opposed to our country’s historical system of centralized power generation. In a centralized system, electricity is generated from a large source, a power plant, and then distributed to cities, towns, and homes, often hundreds or even thousands of miles away. While this system may have helped increase access to electricity early on, it was designed to have a separate class of owners in charge of power generation. The utilities’ profit model of selling electricity to customers can be at odds with their customers owning their own power source.

Promoting distributed generation provides multiple benefits over solely centralized systems. Distributed energy increases the overall efficiency of the transfer of electricity from the source to where it’s used. When electricity is produced closer to where it’s used, transmission lines can be shorter meaning that less energy is lost to heat when compared with longer power lines. Having more points of energy generation can also make a state’s energy grid more reliable and resilient. Distributing generation across many sources means more redundancies in the electricity supply and added security in case some are damaged in severe weather events.

Carve-Outs vs RPS Multipliers

Solar carve-outs are a common form of this policy, broadly setting aside a portion of the portfolio to come from solar technology. Often solar carve-outs have the added benefit of advancing distributed generation through small-scale solar installations. These can be residential, rooftop, community-owned, or just small commercial facilities.

RPS multipliers are another mechanism that states can use to promote specific technologies. Multipliers are a type of carve-out, but instead of reserving a portion of the RPS, they increase the value of the desired technology in its contribution towards the overall requirements. For example, Missouri has a 1.25 multiplier on any electricity generated in the state, as opposed to utilities purchasing it from across state lines. The effect is similar to a carve-out: the state increases demand for electricity generated where they want. Unfortunately, multipliers can have the unintended consequence of leading to an overall lower total amount of renewable energy generated to meet a state’s RPS. If a technology has a higher value towards the RPS, then less of it needs to be generated to hit the target.

RECs and SRECs

Once carve-outs require that utilities procure electricity from a desired source, it’s important for states to verify that they are complying with the RPS. One way for states to do this is through Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) and Solar Renewable Energy Certificates (SRECs).

A REC is created when a facility generates one Megawatt Hour (MWh) of renewable energy and the facility receives the REC as proof. A SREC is the same idea, it’s just specific to solar energy. RECs and SRECs can then be purchased by utilities to satisfy their RPS requirements — they effectively own that unit of renewable energy and are able to prove that they paid for it. All of this information feeds into a state database that tracks the compliance of each utility.

Any generation facility, distributed or otherwise, can sell RECs and SRECs for financial compensation, which serves as an additional incentive to produce renewable energy. Often, RECs and SRECs are sold through a broker, and similar to the way someone might trade on the stock market, the prices can fluctuate. The supply and demand of the REC and SREC markets can affect their current prices. Supply comes from the overall amount of renewable energy produced, and demand is affected by the amount of renewable or solar energy that utilities still need to meet their RPS requirements.

The REC and SREC system is a way to both track a utility’s compliance with the state’s RPS as well as incentivize renewables through a market-based policy, but it’s not without flaws. The certificate guarantees only that one MWh of renewable or solar energy was produced and added to the grid, but the buyer of the REC could be very far away from the power source. REC and SREC markets often exist across state lines, so when a utility purchases a REC, they may have a “greener” carbon footprint without decreasing emissions on its own grid.

Creating Demand for Specific Technologies

Under the policy stacking framework developed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, carve-outs are a market creation policy. After passing foundational policies that remove barriers to access renewable energy, the policies in this secondary category increase demand for renewable energy and create a market in which they can grow.

Effective market creation policies, including carve-outs, can be hindered when there are basic market barriers still in place. That’s why it’s key for states to prioritize foundational market preparation policies, which reduce or remove these barriers. These include passing interconnection standards, net metering, and other policies that prepare a state’s market for renewable energy development. Essentially, if a state is going to require utilities to procure rooftop solar, they have to make sure that people can actually set up rooftop solar in the first place.

Carve-outs, like Renewable Portfolio Standards, create stable demand for renewable technologies by setting requirements that utilities must procure them. Creating this demand provides certainty to investors that the state is committed to growing their market for the carve-out’s technology. This in turn encourages investment in that technology.

Additionally, the REC and SREC trading system is factored into the financing models of a renewable project. Because owners of the certificates can make money from their trading, investors can get an idea of how the project will affect their bottom line in the long term. States that have more ambitious RPSs and carve-outs can create more demand for renewables, which drives up the price of RECs and further incentivizes investment in the projects.Distributing energy resources is about shifting the control of power generation away from solely larger entities. These policies allow people, communities, and local businesses to contribute renewable energy to the grid and they deserve to make money from the RECs and SRECs they sell, just like larger financial institutions.

Read more about net metering in our previous Dashboard Digest article: Building Foundations for Renewable Energy through Net Metering

What Makes Effective Carve-Out Policies?

Carve-outs are an important tool that states can use to increase demand for renewable energy technologies, but they are just one piece of the puzzle. There are many different policies that affect the development of renewable markets and successes and failures can rarely be attributed to just one policy. In general, market creation policies, like carve-outs, benefit from thorough foundational policies that remove or reduce market barriers. Without adequate market preparation, it can be harder for states to develop renewable energy markets.

Clear definition of what qualifies as distributed generation. Generally, distributed generation facilities are renewable energy sources that are sited at a customer’s premises and are connected to the electric grid.

Clear definition of which technologies are eligible to meet the carve-out requirements. The carve-out should ideally support the development of multiple renewable energy sources and define the criteria to be eligible.

Carve-out has ambitious targets and interim deadlines. Like RPSs, ambitious carve-outs are preferable in order to meet the decarbonization needs of the electricity sector. Carve-outs should have interim targets to help utilities comply, but should support a rapid transition away from fossil fuels.

Tracking systems are transparent and publicly accessible. Transparency holds utilities accountable and can help gain public support for renewable energy policies. The public should be able to use REC and SREC tracking systems to verify utility compliance.

Qualified systems should have large capacity limits. While many distributed generators may be small, like residential solar, other larger facilities should also be eligible for the carve-out. Promoting distributed generation is important for grid resilience and including large systems in the carve-out creates demand and incentivizes investment in them.

Carve-outs should be tailored to the state’s goals. No two states are the same, and no two carve-outs are the same. These policies can be difficult to compare because each state has a different history, economy, and goals for renewable energy. One state with an already saturated solar energy market may not need a solar carve-out whereas another state may seek growth in this area.

Penalties should be high enough to incentivize compliance with the state’s carve-out. It’s important not only that a state’s RPS has penalties for utilities who fail to meet their requirements, but that the price is sufficiently high. If the price is too low, a utility could choose to fail to comply with the RPS and look at the fine as an acceptable cost of doing business.

State Example

Arizona

While Arizona may not have the country’s most ambitious Renewable Portfolio Standard (15 percent renewable energy by 2025), the state does have a significant carve-out for distributed generation. The RPS requires that 30 percent of the 15 percent renewable target comes from distributed generation by 2012 and each year after. By 2025, distributed generation should total 4.5 percent of overall electricity sales.

Of the 30 percent requirement, half must come from residential generation, like rooftop solar, and the other half from non-residential non-utility sources. The RPS clarifies that distributed generation refers to a facility sited at a customer’s premises that either provides electricity to the customer or provides wholesale capacity to the utility.

Although Arizona ranks second in the country for solar potential, they still face barriers to building out their distributed generation. Carving out a section of the state’s RPS is an important step to create demand, but it’s only one step in an intertwined stack of renewable energy policies. Like other states, Arizona has a mixed history with distributed energy policies. The state’s utilities have pushed back against expanding distributed generation with measures including the reduction of incentives for solar power. However in 2020, state regulators approved new rules for interconnection standards to make it easier for distributed generation projects to connect to the grid.

About CNEE: The Center for the New Energy Economy was founded in 2011 as a department at Colorado State University by Colorado’s 41st Governor, Bill Ritter Jr. The Center convenes and facilitates dialogue among policymakers and stakeholders, connects energy policy leaders and experts, creates and maintains free, publicly available tools and resources, and publishes energy policy research.

About The State Policy Opportunity Tracker (SPOT) for Clean Energy: The SPOT for Clean Energy is a hub of information on state-level clean energy policy. Intended as a planning aid, the SPOT for Clean Energy aims to inform decision-making by providing policymakers, regulators, and interested stakeholders a clear snapshot of existing state policies and opportunities for future policy adoption.