Climate XChange’s Dashboard Digest is a deep dive on each of the policies that we track in the State Climate Policy Dashboard and an exploration of how these policies can interact with one another to form a robust policy landscape. The series is intended to serve as a resource to state policy actors who are seeking to increase their understanding of climate policies, learn from experts in each policy area, and view examples of states that have passed model policies. We’re beginning our series by exploring renewable energy and energy storage policies.

For nearly half a century, states have realized the benefits of building clean energy markets through net metering, renewable portfolio standards, and other foundational policies. Along the way, states have set goals to reduce emissions from their energy sectors. As some states have committed to total decarbonization goals, Clean Energy Plans represent a way to examine the links between renewable energy policies and propose a path forward.

Read more about policy stacking in our previous Dashboard Digest article: Unlocking Renewable Energy Potential through Policy Stacking

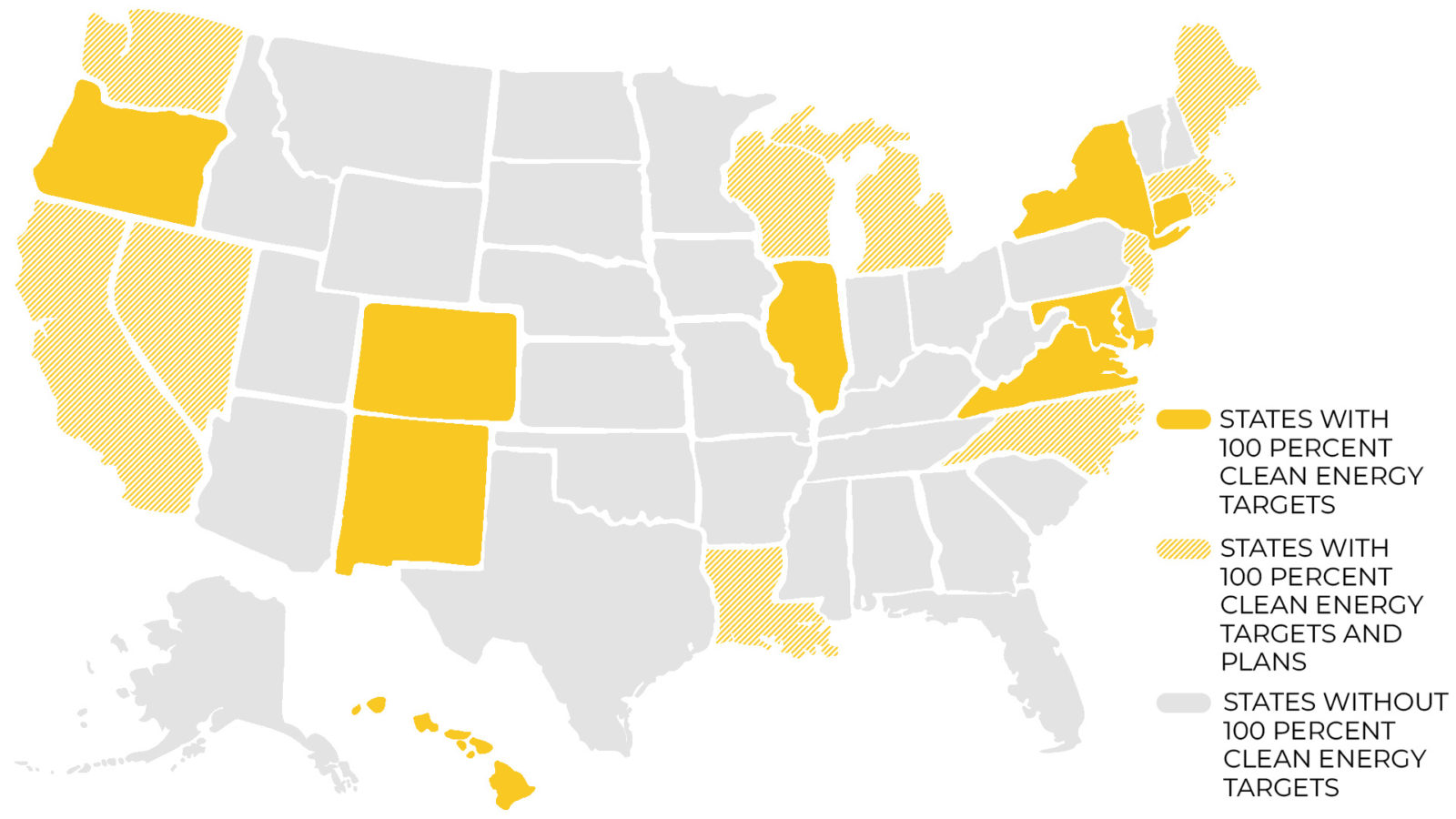

So far, 20 states have committed to 100 percent clean energy goals set for the coming decades. This is an essential step to overall decarbonization, as many scientists agree that the electricity system should be one of the first sectors to lower its carbon footprint. In a somewhat counterintuitive order, many states set these lofty goals before they have formally modeled how, or if, they can be achieved. Still, it’s the state’s responsibility to communicate how they intend to bridge the gap between the present, and their clean energy future.

This article in our Dashboard Digest series dives deeper into the process for how a state creates their Clean Energy Plan, which is arguably as important as the actual contents of the document. This planning process is the focus of the article, and it is vital that Clean Energy Plans are honest, evidence-based, and fairly represent the interest of all stakeholders, particularly those who may have been left out in the past. These plans can shape the direction of a state’s energy system, so there’s quite a lot at stake to make sure the state gets right.

Long-Term Energy Planning

The Complexity of the Grid

State energy systems are complex. Electricity is generated from a variety of sources owned by a number of different entities. The electricity is carried long distances by transmission networks to towns and cities. Then it is distributed through substations, power lines, and transformers to homes and businesses.

It’s not just the infrastructure that’s complex. States have elaborate administrative systems that can enable or hinder a functioning power grid. Permits must be approved, power generators connected to the grid, solar panels affixed to rooftops and routed through electricity meters, and states themselves are connected with one another. Understandably, it can take a long time and a lot of red tape for states and cities to make changes and upgrades to the grid. In order to ensure a modern, reliable, and equitable energy system, states must plan decades ahead.

Distinguishing Clean Energy Plans from State Energy Plans

Forty-two states are engaged in long-term energy planning in the form of a State Energy Plan. This document is created at the direction of the governor or legislature and usually prepared by a state energy department. However it’s important to distinguish these plans, which outline the general energy strategy of a state, from Clean Energy Plans, which outline how a state will meet 100 percent renewable targets.

The fact that State Energy Plans exist across a wide range of states indicates that energy planning alone is seen as a crucial, non-partisan topic. There are a wide variety of stakeholders who know that State Energy Plans can greatly affect their competing interests. However, the stakeholders who propose the plan and the process for how it’s written can mean the difference between a state ramping up production of coal or committing to clean, distributed energy generation.

Even states without bold clean energy targets can (and should) incorporate decarbonization strategies into their State Energy Plans. For example, Texas, not known as a climate leader, published an energy plan in 2008 which identified wind energy as a rapidly growing resource for the state. Now, the production of wind energy has increased six-fold to make Texas the state with the most wind generation. This demonstrates that long-term energy planning can have major impacts on a state’s economy, the results depending on how the plan addresses the concerns and priorities of the numerous stakeholders.

Creating a Clean Energy Plan

Who Writes Clean Energy Plans?

Clean Energy Plans are produced by a variety of executive bodies in a state (e.g. Department of Energy, Department of Environmental Protection) at the direction of the governor or legislature. No matter which agency or department’s name is on the plan, there are numerous other bodies that should be included in the planning process.

Because the energy system is so complex, there is a need for technical expertise to analyze how a state can reach their clean energy goals. This expertise may be found in other state bodies, like the Public Utility Commission that’s responsible for regulating a state’s electricity market. Sometimes, when a state lacks capacity for modeling and analysis, independent consultants can provide valuable support.

Since long-term energy planning has major social and economic impacts, it’s essential to include equity in all stages of the Clean Energy Plan. This can be accomplished with help from a dedicated state environmental justice agency which may include representatives from tribal and frontline communities, state government, and economic sectors.

Energy planning may be technical and complex, but it has significant impacts on stakeholders at all levels. Writers of Clean Energy Plans should make sure that legislators, advocates, business owners, and community members all have an understanding of the plan and are included in the process. Online documents, webinars, and public forums can help states communicate plans to their stakeholders, and there should be ample opportunities for stakeholders to be involved

What’s in a Clean Energy Plan?

Energy Landscape

Clean Energy Plans discuss the current status of a state’s energy system and describe the context for why clean energy goals are necessary. Plans often include a state’s existing emissions and energy portfolios to give a point of reference for how much more work needs to be done. It’s also useful to describe the economic, environmental, and social benefits that will accompany a state’s transition to a clean energy system.

Modeling and Analysis

Clean Energy Plans often include detailed analysis and modeling to demonstrate how the state will meet their (often enforceable) clean energy target. Energy modeling can come in many forms, and project the effects that different technologies and policies will have on a state’s emissions. Massachusetts’ Clean Energy Plan, for example, uses two separate modeling approaches to deliver insight into pathways for the state. The first approach acknowledges that Massachusetts is one member of a regional energy grid and that any changes to the energy grid cannot be isolated from surrounding states. This model identified eight technological pathways that the state could take and assessed each one’s impact on the Massachusetts 2050 net-zero emissions goal. The second approach modeled which policy interventions specific to sectors of the Massachusetts economy would allow the state to achieve the necessary pace of transformation for each of the eight pathways from the first approach.

Policy Recommendations

Clean Energy Plans include policy recommendations that result from this detailed modeling and analysis. The actual policies vary greatly depending on state contexts, and are outside the scope of this article, but may include some common themes:

- How the new mix of clean technologies will affect grid reliability.

- How the plan will take into account emerging technologies like offshore wind, energy storage, and hydrogen.

- What are the impacts of the state’s plan on land-use and the environment.

- How climate change, and the state’s interventions will affect air quality and public health.

- What are the equity impacts and considerations in the plan.

The goal for including policy recommendations in Clean Energy Plans is to present a series of options and strategies for states to move forward. Generally, these recommendations are non-prescriptive but instead present guidance for policymakers in the future, and states can use modeling and analysis of potential pathways to make evidence-based decisions.

Centering Equity

Clean Energy Plans represent an opportunity for states to center equity in their vision for the future. These plans often propose transformative measures that the state intends to take and should address the fact that many frontline and underserved communities are disproportionately impacted by climate change. States should seek input from community members and environmental justice organizations in the planning process. Goals for participation from these communities can be tracked over time to hold the state accountable.

Read more about how to evaluate equity in 100 percent clean energy laws.

Environmental justice advisory committees are an important part of equitable clean energy planning. It’s vital that states engage directly with stakeholders, but advisory bodies and task forces can help implement community priorities with technical knowledge. These committees should be diverse and provide input and suggestions for how to best include frontline communities in the stakeholder engagement process. California’s Clean Energy Plan, the SB 100 Report, included input from the state’s Disadvantaged Communities Advisory Group with a subcommittee specifically focused on the plan. The body was formed from the Clean Energy and Pollution Reduction Act of 2015 to ensure that disadvantaged communities, including tribal and rural ones, benefit from all clean energy initiatives.

States must be honest and self-reflective when incorporating equity into all aspects of their Clean Energy Plans. It’s important for states, separate from these documents, to define environmental justice communities so they can be prioritized when delivering the benefits of clean energy. In order to not repeat the past, there should be a detailed analysis of how these communities have been impacted by inequitable energy practices, and how the state can remedy those injustices.

Read more about environmental justice on the State Climate Policy Dashboard.

State Example

Washington

One of the best examples of a Clean Energy Plan is Washington’s State Energy Strategy from 2020. The plan, which was previously updated in 2012, outlines how the state will achieve its ambitious Renewable Portfolio Standard of 100 percent carbon-neutral energy by 2030, and 100 percent renewable or zero-emitting energy by 2045. The plan was written by the state’s Department of Commerce, and won the State Leadership Award from the Clean Energy States Alliance. The state legislature created a 27-member advisory committee that consists of legislators, government officials, and representatives from civic organizations, utilities, and other public interest advocates.

State law in Washington outlines three goals for its energy strategies:

- Maintain competitive energy prices that are fair for consumers and businesses,

- Increase competitiveness by fostering a clean energy economy and jobs through business and workforce development, and

- Meeting the state’s obligations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

By codifying this language in law, Washinton state created stable, long-term targets for clean energy planning.

The Clean Energy Plan opens with a section on how the state will build an equitable clean energy economy. This section includes data on environmental health disparities for BIPOC communities and lists a seven-step process for centering equity in all parts of the clean energy planning process. These steps include developing affordable internet infrastructure in rural and under-resourced communities, centering program design on reduction of energy cost burdens, and incorporating health disparity metrics into energy planning.

Washington’s State Energy Strategy also explores five decarbonization pathways that the state can take to meet its goals and investigates how policy changes in each one would affect emissions reductions. The state examines electrification, transportation, fossil fuel heating, grid infrastructure improvements, and demand-side behavioral changes. Each model finds the most cost-effective way for Washington to still meet their 2030 and 2050 emissions targets.

The outcomes from the policy recommendations in Washington’s plan won’t be clear for years, but already the state has taken major steps to push forward clean energy policies. Since the State Energy Strategy was published, Washington has passed several policies that address recommendations mentioned in the document:

2021:

- The Climate Commitment Act (SB 5126) established a cap-and-invest program and set a goal that 40 percent of clean energy expenditures will benefit overburdened communities and vulnerable populations.

- The HEAL Act (SB 5141) requires that several state agencies include environmental justice in all agency strategic plans, codifying the process that was included in the State Energy Strategy.

- HB 1091 established a Low Carbon Fuel Standard which requires suppliers to lower the carbon intensity of fuels.

2022: