Climate XChange’s Dashboard Digest is a deep dive on each of the policies that we track in the State Climate Policy Dashboard and an exploration of how these policies can interact with one another to form a robust policy landscape. The series is intended to serve as a resource to state policy actors who are seeking to increase their understanding of climate policies, learn from experts in each policy area, and view examples of states that have passed model policies. We’re beginning our series by exploring renewable energy and energy storage policies.

States across the country are increasing the ambition of their climate goals over the coming decades. Hawaii, California, Washington, and several others have even committed to running on entirely clean power. Legislatures and executive branches can enforce action to achieve these targets, but one key player has the potential to stand firmly in the way: utilities. Electric utilities, especially investor-owned ones, are in business to make a profit, but that motive doesn’t always line up with what we need for a clean power grid.

It’s no small feat to change how politically-powerful monopolies operate, but aligning the utility business model with climate goals is an essential part of decarbonizing the power sector. Most Americans don’t have a lot of choice when it comes to their utility, so if these companies are going to support the transition to clean energy, we need to make sure that it’s in the best interest of all stakeholders — including the utility itself.

In this article for our Dashboard Digest series, we spoke with Cara Goldenberg, a Manager at RMI who has written a lot about how to align utilities with climate goals. Goldenberg helps us understand why utility companies need reform, what those changes can look like, and what levers to pull to make these changes happen.

Read more about utilities in our previous Dashboard Digest article: The Grid Isn’t Broken, But Still Needs Fixing

The Problem With How Utilities Make Money

Utilities provide public services, like electricity, and can be owned by shareholders, municipalities, or managed cooperatively by their customers. Changing the way that all of these entities deliver electricity is critical, but investor-owned utilities (IOUs) supply power to most of the country and are the biggest risk to our climate goals. IOUs vary in size, structure, and the services they provide, but they are all for profit companies and have a responsibility to their investors. This fiduciary duty alone doesn’t make utility business models incompatible with climate goals, but it explains why the current model exists, and why utilities pose a threat to climate goals. RMI’s report co-authored by Goldenberg, Navigating Utility Business Model Reform, lays out some of the issues with the traditional utility business model.

Read More: Navigating Utility Business Model Reform

Revenue is Linked to Energy Sales

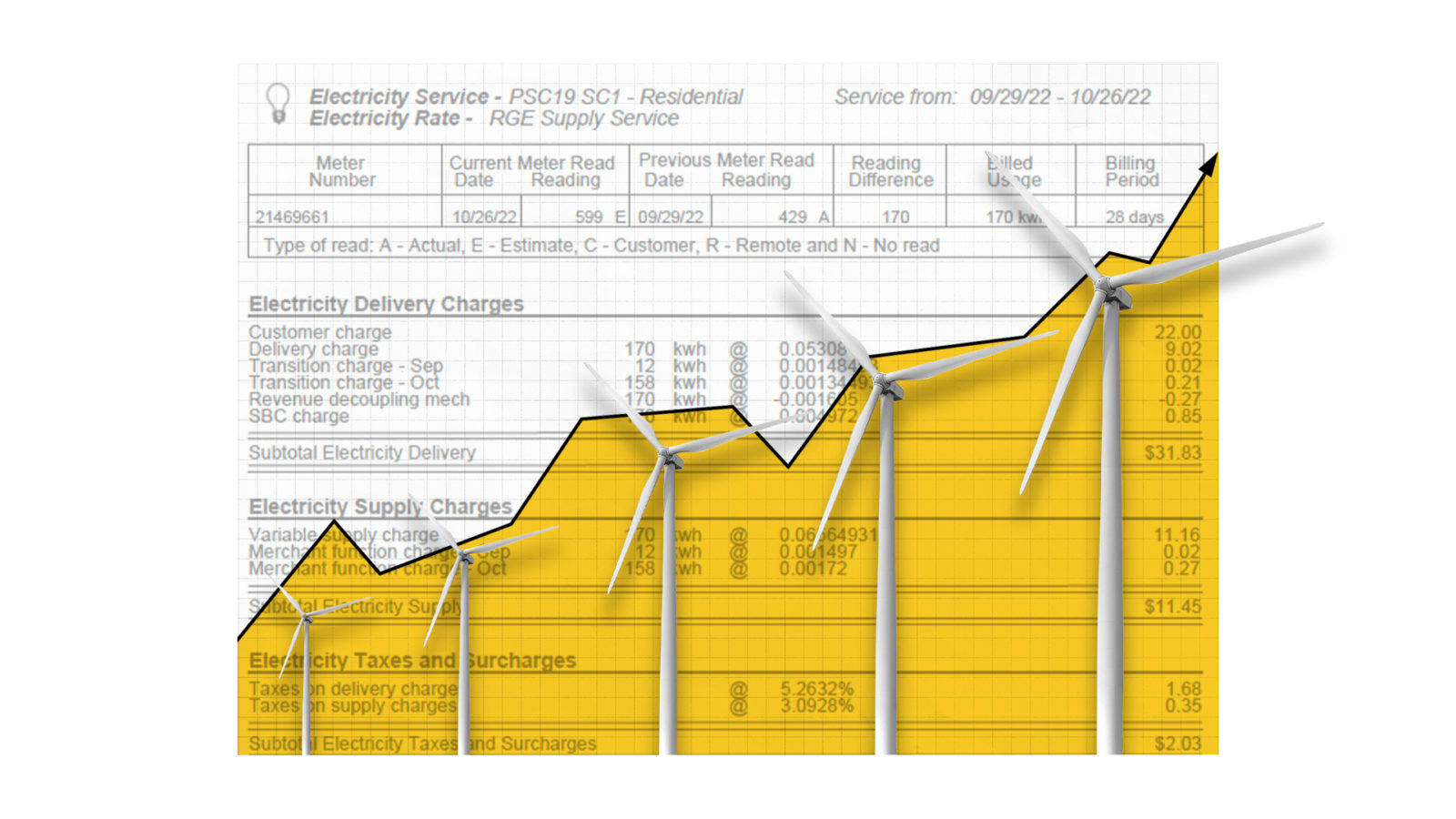

Traditionally, utilities make money based on the amount of electricity that they sell — which in some ways makes sense. After all, most companies make greater profits based on the amount of goods or services that they sell. The problem is that in order to decarbonize our economy, we need to be much more efficient about our energy use, especially as demand increases as we electrify buildings and transportation. Utilities are incentivized to maximize energy sales because of a regulatory process known as a rate case.

Usually once a year, utilities and regulators meet to decide what electricity rates should be — in a way that keeps energy affordable, while still earning a reasonable return for utility shareholders. During this process, utilities propose what they need to build and spend to meet the grid’s needs during the next year, and regulators approve or deny parts of the proposal. Once the back and forth is finished, regulators come up with the amount of money the utility can make during the next year, known as the revenue requirement. The revenue requirement is then divided among the number of a utility’s customers and the projected energy demand to determine electricity rates.

Under the traditional business model, a utility’s revenue is tied to the amount of energy they sell, they’re incentivized to sell a lot, often more than necessary to guarantee that they’ll reach their maximum revenue. Usually any excess revenue that’s made is returned to ratepayers by reducing rates in the future, but this link between sales and revenue disincentivizes a utility from promoting anything that would reduce the demand for electricity, like energy efficiency or rooftop solar.

Building Expensive Infrastructure Leads to Greater Returns

The ratemaking formula that regulators use to determine a utility’s revenue requirement creates an incentive to invest more in capital expenditures (power plants, transmission lines, and other physical assets) than on operation and maintenance expenditures (fixing equipment, and other administrative costs). In the formula, utilities earn a predetermined rate of return for shareholders only on capital expenditures (capex), whereas operation and maintenance expenses (opex) are passed directly on to customers in their electricity rates.

Since capex contributes to profits, every dollar spent on new infrastructure will earn greater returns for investors than the same amount spent on maintaining current assets. This capex bias can potentially incentivize utilities to propose expensive, and sometimes uneconomic, capital investments because that will earn them the greatest return for their investors.

Capex bias can lead utilities to both invest in expensive infrastructure, while at the same time neglect equipment that already exists. A high profile example of potential capex bias happened in 2018 when Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), the nation’s largest utility, completed a $1.3 billion pipeline expansion project. That same year, PG&E admitted that their aging power lines in California caused a massive wildfire that killed dozens of people and caused millions of dollars in damages. While capex bias alone can’t fully explain this tragedy, it illustrates a potential reason why utilities like PG&E may ignore routine grid maintenance in favor of capital investments that will earn returns for shareholders.

Aging, uneconomic assets

Much of the country’s fossil fuel infrastructure has, or probably will, become uneconomic when compared with renewable alternatives. The problem is that in many cases, utilities are disincentivized to retire these failing investments. Utility companies need to secure loans to build major capital projects, which are then paid back over time, through electricity rates. This can disincentivize utilities from investing in additional clean power, because of the rate increases customers would face for both the new infrastructure and what they’re already paying for old fossil fuel plants.

Failing to address needs of modern grid

As utilities are allowed to act as monopolies, they are expected to meet the needs of the public that they serve. However, in most cases, customers can’t shop around for another utility if they don’t like the one they have. Historically, regulators mandated that utilities provide safe, reliable, secure, and affordable electricity to all customers, but a modern electric grid has new demands that utilities aren’t currently incentivized to support.

For example, distributed energy resources, like rooftop solar, are key to a resilient grid, but they threaten the traditional utility business model. If customers can produce their own power, utility companies risk not selling enough energy to reach their revenue requirement. This creates a disincentive for utilities to support interconnection for distributed renewable resources.

What Does Utility Reform Look Like?

Since utility reform is a complicated issue, there are a number of different policy options that address different aspects of the traditional business model’s shortcomings.

RMI’s report, Navigating Utility Business Model Reform, lists five objectives that utility reforms should seek to accomplish, benefitting utilities, ratepayers, and the grid:

- Remove utilities’ incentives to grow energy sales: Traditionally, higher demand for electricity makes it more likely the utility will reach their maximum revenue, so they have a disincentive to support anything that would decrease demand.

- Realign profit-making incentives: How utilities make money can be reimagined and centered around the needs of a modern grid.

- Develop new utility revenue and profit opportunities: While we need to promote energy efficiency, a rapidly electrifying economy will undoubtedly expand electricity demand into new areas and can present opportunities for utilities to provide new services and realize new profits.

- Revise risk and value sharing: Balancing the way that business risks are borne between ratepayers, utility companies, and their investors.

- Encourage cost containment: Practices that promote economically efficient business operations can provide major benefits to ratepayers and the grid.

Types of Utility Reform

RMI’s report divides utility reforms into four categories, each addressing different aspects of the traditional utility business model.

Adjustments to the Cost-of-Service Model

- Revenue Decoupling: Through the traditional ratemaking formula, the revenue that utilities are allowed to make is directly tied to the amount of energy that they sell. Even though there is a maximum revenue with a fixed electricity rate, utilities are encouraged to sell as much energy as possible to hit this target. This reform option proposes separating revenue from energy sales, making it less important to the utility to sell a lot of electricity. When decoupling is used, the utility can charge a variable rate for electricity based on current sales in order to still achieve their revenue requirement. If there are fewer overall sales, utilities can charge higher prices in order to recover more revenue, and vice versa. According to Goldenberg, utilities have generally been okay with decoupling. “It really does allow them to have more predictability in terms of the revenues they’re going to collect.” Since utility revenues are no longer tied to energy demand, they’ll have fewer objections to anything else that would reduce demand, like energy efficiency programs. It also benefits ratepayers by reducing swings in energy costs as demand increases in the summer and winter months.

- Multi-year Rate Plans: Traditionally, utilities and regulators convene annually to set electricity rates. As rate cases determine how much revenue a utility can make (and pay its investors), there’s a lot at stake in this process, which requires time and resources for regulators to ensure that utilities make responsible decisions. There can also be multi-year rate plans, where regulators set revenue requirements for the next three to five years. This is done by projecting future energy demand and utility expenses if the business is run efficiently. Multi-year plans incentivize utilities to contain their costs, because revenues have been set ahead of time. If done successfully, this can benefit ratepayers (through lower electricity rates), utilities (with greater flexibility to make long term business decisions), and regulators (because it relieves the resource strain of annual rate cases).

- Shared Savings Mechanisms: This reform option incentivizes utilities to make business decisions that save money. Regulators project a baseline for what the utility should spend, and any additional savings are split between the utility as profit, and rebates to ratepayers. This reform helps incentivize efficient business practices from utilities in a way that can actually increases overall profits. Because this reform option doesn’t necessarily reduce energy use, it is often included as a design element of other reform policies.

- Performance Incentive Mechanisms: Through performance incentives, utilities can earn rewards for achieving desired outcomes defined by regulators. These include achieving greenhouse gas emissions targets, customer satisfaction, utility operations goals, or other valuable goals. This reform option doesn’t remove a utility’s incentive to grow sales, but creates new profit opportunities and can complement reform options that may reduce demand for electricity.

Leveling the Playing Field

- Changes to the Treatment of Capital and Operational Expenditures: Current ratemaking formulas can potentially create a bias for capital expenditures (capex) over operational expenditures (opex). This occurs because utilities earn profits on capex (through a fixed rate of return), but not on opex, which are passed straight through to ratepayers. One of the most promising ways to eliminate the bias is with a new formula called totex ratemaking. With totex ratemaking, capex and opex are combined and the total expenditures are divided into slow money (which will earn returns for shareholders) and fast money (which won’t) based on a predetermined capitalization rate. By pooling the capex and opex together before applying the capitalization rate, utilities are no longer incentivized to prefer spending on capex solutions when opex could have the same returns. This reform option currently does not exist anywhere in the U.S., but is gaining traction where it is used overseas. Goldenberg finds the potential of totex ratemaking promising: “From our point of view, it really is the most comprehensive way to address this desire of utilities to invest in capex options over opex, even if they [opex] are more cost effective.”

- New Procurement Practices: Utilities can be required to engage in procurement practices that accomplish a state’s needs, including specific technology solutions, distributed resources, or cost-efficient options. This policy option is flexible to meet the needs of a state’s grid and encourage cost containment by the utility.

Retirement of Uneconomic Assets

- Securitization for Uneconomic Assets: This option allows utilities to refinance underperforming assets, such as coal power plants, and pay them off through low-interest bonds. Customers will see reduced rates because of the lower interest rate and the utility company’s savings from securitization can be reinvested into clean energy projects. This type of reform has been used for decades, but has recently been key to phasing out coal power generation. Bonds are backed by ratepayers, so securitization requires regulatory approval and sometimes legislation to ensure bonds receive a high rating.

- Accelerated Depreciation for Uneconomic Assets: Physical assets, like power plants, depreciate in value over the course of their useful life. Depreciation expenses are factored into the revenue requirement formula in an annual rate case, and passed onto ratepayers just like operation and maintenance expenses. If a utility’s asset, like a coal plant, is retired early, regulators have the option to accelerate its depreciation schedule. This would result in lower overall returns for the utility, but would help with cash flow because customers would pay higher rates to pay off the depreciation sooner. Although ratepayers have higher bills short-term, paying off these assets sooner results in overall lower payments and gives utilities the freedom to invest in cleaner and more competitive energy solutions.

Reimagined Utility Business Model

- Platform Revenues: Utilities generally oppose distributed energy resources because when customers produce their own power, they demand less energy purchased from the utility. This reform option allows utilities to earn additional sources of revenue by providing products and services that aid distributed energy producers and facilitate market development. This can ease the potential loss in revenue from an overall decrease in demand and can be complemented by other reforms like revenue decoupling.

- New Utility Value-Added Services: This creative and flexible reform option gives utilities the opportunity to provide new services that provide value to a changing grid, and earn additional revenue. These services are ones that the utility was formerly not expected to provide, but would benefit ratepayers and the grid. These may include: offering energy storage infrastructure, electric vehicle charging memberships, or utility-sponsored community solar.

What Drives Utility Reform?

Utility reform may pose threats to the current business model, but Goldenberg doesn’t think it has to be black and white: “There really is an opportunity to design it in a way that is a win-win-win for the utility, for customers, and for the environment.” Each of the previously mentioned reform options addresses a certain objective(s) of utility reform, but none should be considered a perfect solution. Because of this, certain reform options may be preferred and proposed by different stakeholders, depending on their interests.

Utility Driven

Utilities themselves are oftentimes proponents of utility reform for a few different reasons. IOUs are for-profit businesses that should be expected to operate by the rules of our capitalistic economy. In some cases, traditional business operations may make the most economic sense, but utilities may also see the writing on the wall and choose to initiate reforms to get ahead. Incoming climate-friendly administrations or legislatures, state and federal mandates, and increasingly competitive renewable and distributed energy resources can cause utilities to propose reforms to ensure they are still able to profit under a new system.

It should also be noted that utilities are varied and their operations are heavily influenced by the company’s management and leadership. Climate-friendly CEOs can have huge impacts on a utility’s operations, including initiating reforms that challenge the traditional business model. If a utility anticipates being able to meet their own internal objectives, they may also support regulatory performance incentive mechanisms as a way to earn additional profits.

Regulator and Legislator Driven

Reforms can also be initiated through legislation and by state regulators. For example, legislatures may pass a clean energy standard, and in response, regulators could initiate utility reforms to ensure that the electricity supply remains affordable and reliable. It’s also important to note that regulatory agencies across the country differ in their resources and capacity to protect ratepayers and keep utilities in check. For reforms to be effective, it’s vital that all state agencies are aligned with climate goals and are sufficiently enabled to implement reforms.

Stakeholder Driven

Ratepayers and other stakeholders can influence the utility reform process at different levels. Goldenberg stressed the importance of stakeholder representation in utility processes, when utilities usually have many more resources. “They [utilities] can come in with 5-10 representatives to these meetings, and there’s one representative for the community group or the environmental group.” Stakeholders can provide comments and testimony during formal regulatory and legislative proceedings. They can also organize and convene their own investigative committees or participate in ones organized by regulators, and can lobby legislators to influence the content of utility reform legislation.

State Example

New York

In 2014, the New York Public Service Commission (PSC) issued a proposal to realign the way that utilities operate in order to spur development of the state’s clean energy economy. The PSC’s Reforming the Energy Vision (REV) Initiative is an ongoing effort to change the way that the state’s electricity market operates.

NY’s REV Initiative encompasses a range of policy changes to transform the state’s electricity industry — making it more efficient, clean, reliable, and consumer oriented. The PSC’s proposal specified that energy efficiency and distributed energy resources (DERs) would be key components of their vision for the state’s energy grid.

The primary utility reform in REV ensures that utilities have new revenue opportunities while they act in support of developing a distributed energy system. These new opportunities would come from Performance Incentive Mechanisms and Platform Revenues.

Performance Incentive Mechanisms allow utilities to be rewarded for using customer-sited solar and other demand-side approaches to meet the grid’s power needs. Additionally, each utility can propose Earning Adjustment Mechanisms to earn profits for accomplishing goals that meet REV objectives. These goals can include overall system efficiency, customer engagement, greenhouse gas reduction, and improved interconnection processes.

Under REV, utilities can also earn revenue for offering DER providers access to utility systems. This can include communication services, data sharing, and third-party financing for home energy technologies.

As REV is still an ongoing process, all of its impacts remain to be seen, however the state’s PSC references a project by Consolidated Edison as an early success: the Brooklyn Queens Demand Management Program. The utility used a combination of solar power, batteries, and energy efficiency — instead of constructing a $1 billion electrical substation in Brooklyn — to meet the needs of the grid. With this project, the utility utilized an operational expense instead of spending on capital to meet the same goal, and was rewarded with profits for doing so. This early project represents a way that power companies, ratepayers, and the energy grid can benefit from utility reform.