Climate XChange’s Dashboard Digest is a deep dive on each of the policies that we track in the State Climate Policy Dashboard and an exploration of how these policies can interact with one another to form a robust policy landscape. The series is intended to serve as a resource to state policy actors who are seeking to increase their understanding of climate policies, learn from experts in each policy area, and view examples of states that have passed model policies. We’re beginning our series by exploring renewable energy and energy storage policies.

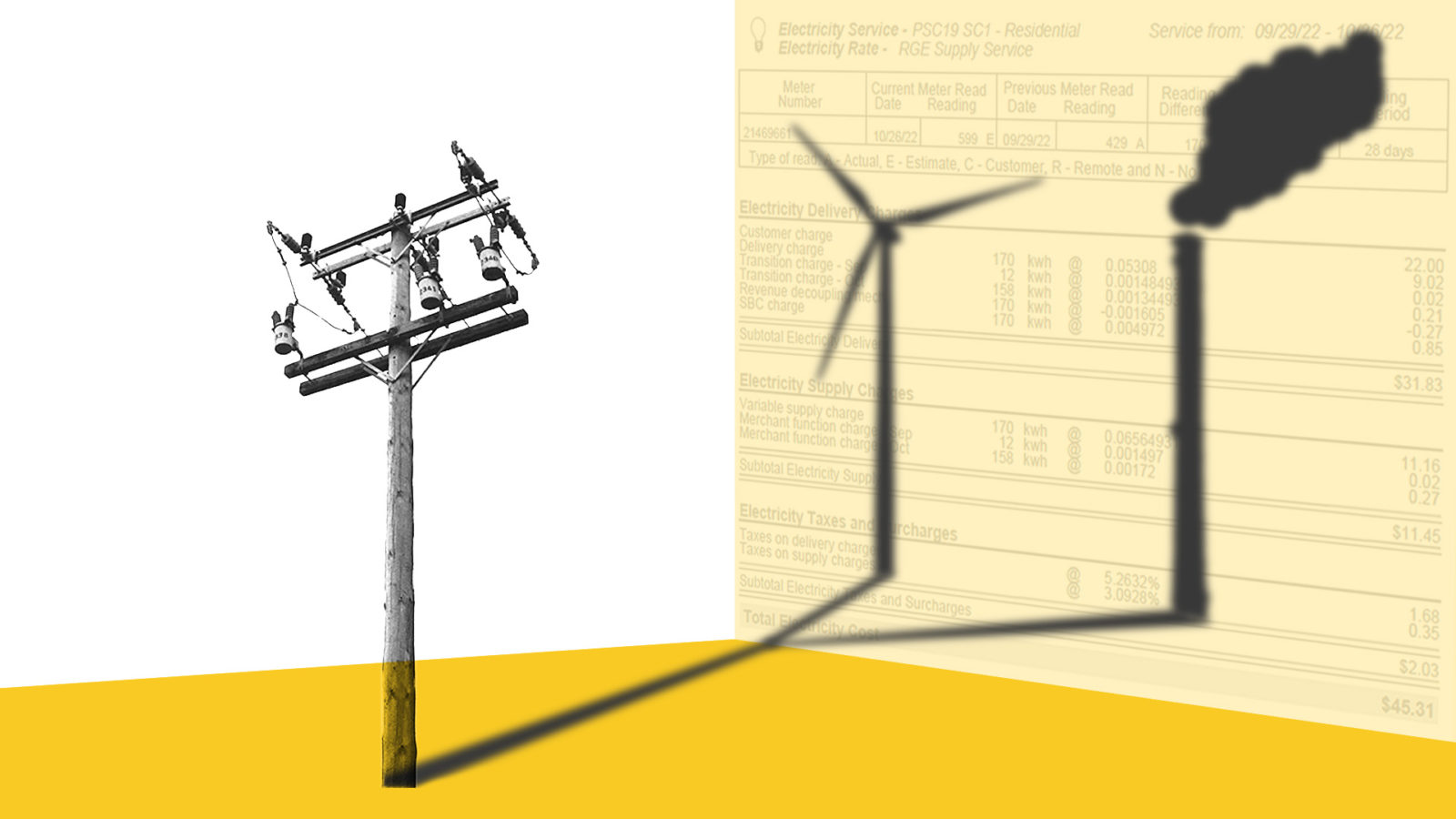

Most people get their electricity from the same mix of power as their neighbor. In fact, it’s impossible to distinguish between the electrons traveling to each house from the electric grid. Early on, electricity service was fairly simple: you could choose to have electricity or not. But as customers’ preferences and expectations evolved, many were no longer satisfied with the lack of consumer choices around what they were purchasing.

Today, customers in many states can choose where they source their electricity. In these competitive markets, privately owned power generators market their electricity, and customers can choose based on their values and preferences. However in states where customers rely solely on the utility for electricity, governments can help them gain more control over their choices through utility green power options. These voluntary programs give ratepayers varying degrees of choice over their electricity service when they live in a state without a competitive market.

In this article for the Dashboard Digest, we’ll explore three different types of voluntary green power programs: green pricing, green tariffs, and community choice aggregation. These programs have different benefits and limitations, but all expand options for ratepayers to choose their energy sources and can increase overall renewable energy capacity.

A Lack of Electricity Options

After Thomas Edison invented the first practical light bulb in 1879, he reportedly said that “none but the extravagant will burn tallow candles,” once his technology was affordable. Though electrification was slow at first, it began to pick up steam once power companies began to consolidate their businesses and develop into large, vertically-integrated monopolies. These electric utilities, along with support from the federal government became very successful in connecting homes and businesses to the rapidly forming electric grid. Utilities used centrally located large-scale power generators to provide electricity for customers in their service areas. At the time, this made sense and met the needs of utility customers.

Reigning in the power of electric utilities, states were tasked with regulating their business to ensure they acted in the public’s interest. But by the second half of the 20th century, people began to question the status quo as energy prices skyrocketed. Edison’s notion of affordability was failing, and now electricity was a necessity for most people. People began to demand alternatives to fossil fuels, the primary sources of electricity at the time. This led to increased investment, and state policies to support renewable power sources.

By the 1990s, it was clear to many states that the monopolistic electric utility model was not working. In an effort to introduce competition into the industry and cut costs, states began to deregulate, or restructure, their electricity markets. In a restructured market, investor owned utilities were barred from owning the sources of power generation. Customers in these states can choose their own electricity supplier, instead of purchasing power through their utility. This customer choice can not only result in lower rates, but also allows consumers to match their source of electricity with their preferences.

In states that kept their traditionally regulated market, consumers don’t have the same opportunities to choose their power provider. The default utility was responsible both for procuring power and for distributing it to homes and businesses. Because ratepayers in these states are required to use their electric utility, any solutions to increase consumer choice would have to exist within that framework. Over the past few decades, policymakers and regulators have envisioned a variety of ways to give these consumers various degrees of choice over their energy sources.

Read More: A (Somewhat) Brief History of Utilities

Green Pricing

Market research from the 70s, 80s, and 90s found that not only did consumers prefer renewable energy to fossil fuel alternatives, but they were also willing to pay more for it. In response to this, some utility companies in regulated markets began to offer voluntary services where their customers could opt in to add renewable power to the grid. These were called green pricing programs.

In green pricing programs, customers pay a premium on their normal electricity bill to purchase renewable energy, usually either “blocks” of power, or a percentage of their overall energy use. The utility company agrees to procure the corresponding amount of renewable energy on their behalf, with the premiums representing the additional cost the utility must pay to purchase, or generate, that power.

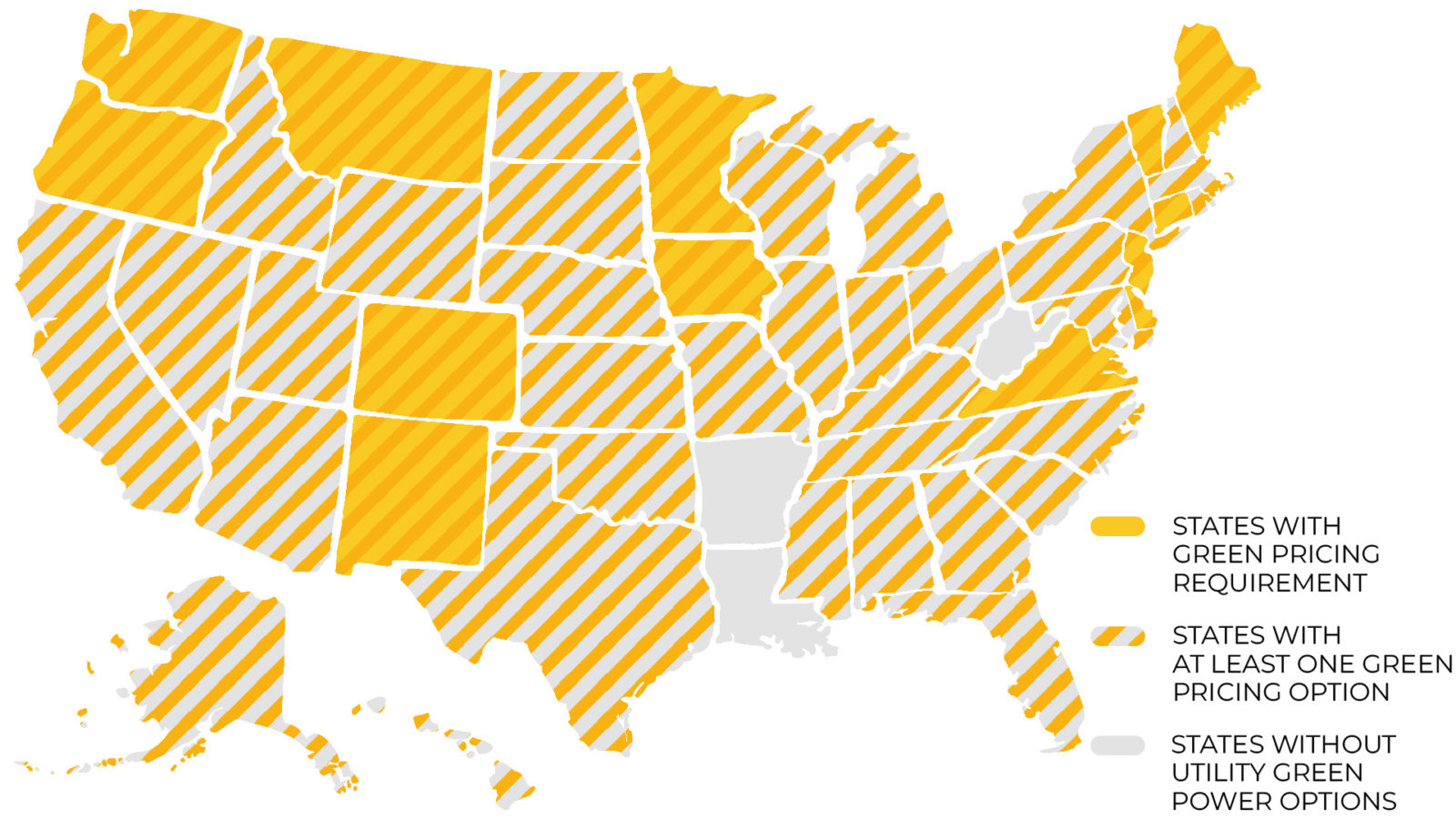

Utility green pricing programs have become very popular nationally. All but three states have at least one utility that offers green pricing programs with a total of more than 1 million customers in 2020, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

It’s important to note that there’s no physical distinction between the energy used by a customer who participates in a green pricing program, and their neighbor who doesn’t. The renewable electrons added to the grid from a wind turbine are mixed with ones from solar, nuclear, and fossil fuel sources. All of that energy is distributed to homes and businesses, without distinction between who is paying for cleaner energy. Because green pricing customers are adding renewable energy to the grid, they do receive cleaner energy, but so does everyone else.

What customers of these programs do receive are Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) in addition to their electricity. These RECs represent an amount of renewable energy that was generated, and are used as a way for utilities, businesses, and individuals to prove that they are running on clean energy. For the most part, when a business says that they are using 100 percent renewable energy, they’re purchasing enough RECs to offset their total energy use. In green pricing programs, the utility may purchase the REC from a third party renewable power generator, or it may come from their own generators. Then, when someone signs up for the program, the utility retires the REC on the customer’s behalf so that they can claim the quantity of clean power.

Benefits

- Adds renewable energy to the grid. In states with Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPSs), utilities already have requirements to procure renewable energy. Green pricing programs can add renewable energy to the power grid in addition to the state’s requirements.

- Reduces the carbon footprint of businesses and individuals. While participation in green pricing programs doesn’t affect a customer’s actual mix of energy, participants can correctly claim that they are offsetting their energy use with cleaner power that’s being added to the grid. When combined with energy efficiency measures, voluntary green pricing programs can help reduce the impact of carbon emissions from homes and businesses.

Limitations

- Higher energy costs. While many customers may be willing to pay more for clean energy, the additional cost can limit the amount of program participants. This is especially important when national average electricity costs are as high as they’ve been in decades.

- Limited choice in the mix of renewables. Although better than nothing, participants in utility green pricing programs usually have a limited choice in the composition of the renewable energy mix that they’re paying for. Different states have varying definitions of what renewable energy means, and green pricing participants may not have a say in what they’re purchasing. For example, Michigan considers energy derived from burning waste to be renewable, though this energy source has a whole host of environmental and equity concerns.

- Utility may not offer a green pricing program. Green pricing programs are also limited by whether or not the utility offers it. States where customers lack competitive retail choice can pass laws requiring utilities to develop green pricing programs, which just 13 states have done so far.

What States Can Do

States with regulated electricity markets can pass legislation that requires utilities to offer green pricing programs to their customers in lieu of having competitive retail choices. Some state laws also require utilities to periodically inform their customers of the green pricing program.

Examples:

- Washington – Utilities must inform customers quarterly of the green pricing program.

- Virginia – Utilities must offer customers an option to purchase 100 percent renewable energy.

- New Mexico – In addition to green pricing, utilities must develop an educational program to inform customers of the benefits and availability of the green power option.

Green Tariffs

In competitive electricity markets, where customers can choose their electricity provider, large corporations can use their buying power to have an extra advantage. Large companies, usually ones that use a lot of energy, can enter into Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with specific renewable energy suppliers. The PPA is a contract where the power producer will provide clean energy (in the form of RECs) to the corporation at a fixed price for a long period of time, sometimes 10-15 years.

In states that don’t have retail competition, utilities can offer their own version of a PPA known as a green tariff. These relatively new programs allow corporations to enter into a PPA-like contract, but with the utility instead of the third-party power producer. The utility acts as an intermediary between the corporation and the renewable energy generator, agreeing to purchase clean energy on their behalf. Instead of paying the normal rate for electricity, green tariff customers negotiate a modified rate structure to reflect the costs of renewable projects that are contracted for the electricity service.

In a green tariff program, corporations can offset their energy use with RECs and have long-term stability in energy expenses, while the renewable generator has guaranteed revenue for a long period of time.

Benefits

- Long term stability. Long-term electric rate stability is beneficial for both utilities and corporations. Corporations are able to plan years in advance while being protected against unforeseen price increases. With years of guaranteed revenue, utilities can better plan for capital investments, infrastructure improvements, and grid modernization.

- Enables new renewables to come online. Though it’s becoming more affordable, new utility-scale renewables can be expensive, and having guaranteed revenue can help build new projects. With a green tariff, utilities may need to build the renewable assets necessary to meet the company’s energy needs, meaning that these contracts can actually add additional renewable capacity to the power grid.

- Avoids shifting program costs to non-participating customers. Specific renewable projects are usually linked to each green tariff contract, meaning that these programs avoid forcing non-participating customers to pay for the cost of additional renewable capacity.

- More control over renewable mix. Because corporations and utilities agree on the green tariff contract, the corporation usually has greater control over the type of renewable energy they’re adding to the power grid. The options depend on what resources are available to the utility, however there is more control than is available to green pricing customers.

According to the Center for the New Energy Economy, corporate green power contracts (like green tariffs) comprise just four percent of all voluntary green power customers, but account for 68 percent of renewable energy sales.

Limitations

- Only offered to large electricity customers. Green tariff programs stipulate which corporate customers are eligible to participate in the program. They are often limited to those with higher annual energy use.

What States Can Do

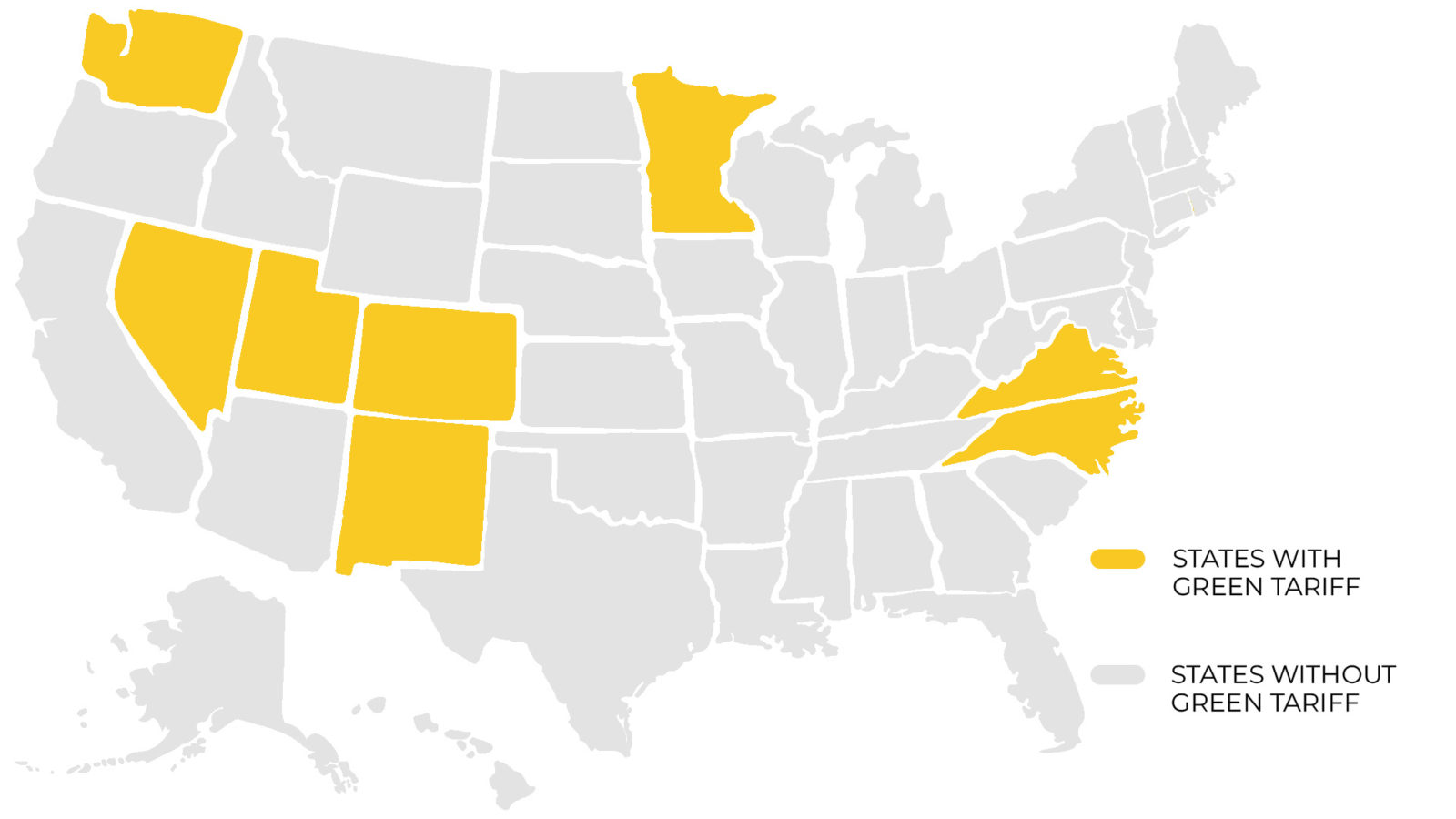

State regulators can proactively encourage utilities to propose green tariffs, and approve the programs. They are currently not available in every state, just 39 utility green tariffs have been proposed or approved in 21 states.

Examples:

- Nevada – The NV GreenEnergy Rider tariff is open to customers that have an annual load of at least 1 megawatt.

- Tech Giants – Google, Facebook, and other tech companies have made recent deals to procure significant amounts of clean energy through green tariffs.

Community Choice Aggregation

Utility green tariffs and PPAs can allow large corporations a choice over their electricity supply, but individuals and smaller businesses don’t have the same negotiating power. A more recent solution called Community Choice Aggregation (CCA) allows municipalities to use the collective buying power of entire communities to choose their power sources.

With CCA, local governments are able to procure power on behalf of their residents, instead of going through the utility. The government uses the higher aggregate load of energy and long-term predictability to achieve the collective buying power to successfully negotiate with independent power producers. The result is often cleaner, more affordable energy than what’s offered by the default utility. In a community with a CCA program, the utility company is still responsible for energy distribution, even if they aren’t procuring it.

In general, CCAs are opt-out programs, meaning that by default every electricity customer is enrolled in the CCA. If a customer wishes not to participate, they must take the initiative to opt-out and would then have their power procured by the utility. Opt-out provisions are key in CCAs because they ensure higher participation, which bolsters the government’s buying power and can help negotiate better electricity rates. And because CCAs are usually less expensive than the utility’s service, opt-out provisions are likely to be favorable.

Benefits

- Potential to save customers money. Aggregating the community’s energy load gives local governments collective buying power to procure energy at competitive prices. These rates are often cheaper than what residents would pay the default utility, and some CCAs reinvest proceeds into the community. Because many CCAs have opt-out provisions, residents don’t need to do anything to benefit from the reduced rates.

- Enables communities to shift to renewables. CCAs not only give residents greater control over their sources of power, but allow entire communities to align their electricity supply with their climate and energy goals. Additionally, CCAs put pressure on utilities to set more ambitious climate goals in order to compete with the CCA.

- Gives customers more control. In competitive electricity markets, customers can choose which energy supplier fits their energy preferences. In regulated states, CCAs can give consumers more freedom to choose how they power their homes and businesses when there is no competitive market available.

Limitations

- Potential for utility pushback. CCA programs introduce competition in states with regulated electricity markets, which can threaten utility revenues. New Hampshire CCAs faced pushback from utilities in 2021 in the form of a proposed amendment that would weaken the state’s original enabling legislation, but advocates in the state were able to fight off the bill.

What States Can Do:

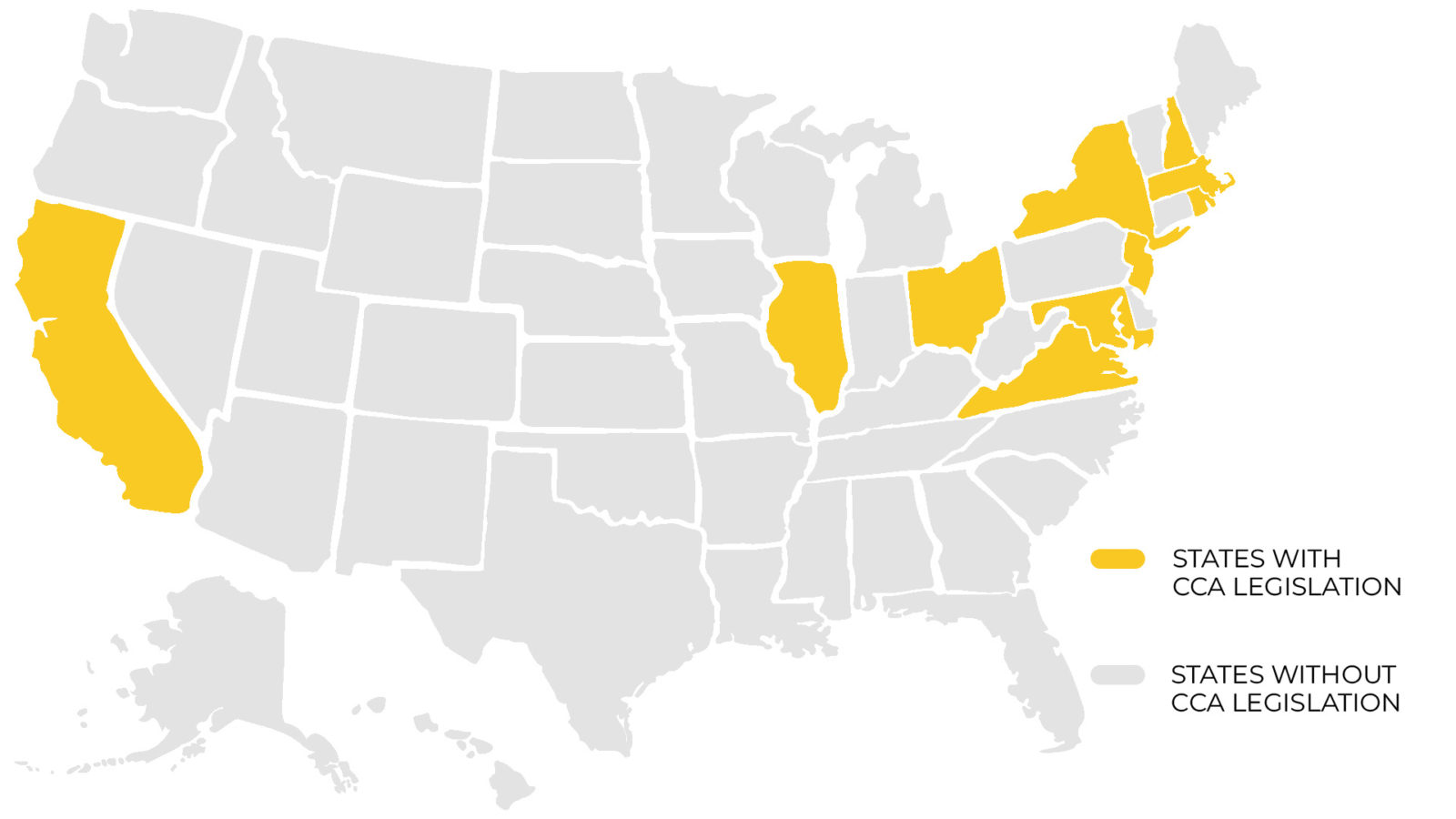

CCAs require legislation to be passed at the state level to allow communities to aggregate their electricity load to procure power separately from the utility. Currently, just ten states have enabling legislation for CCA, with New Hampshire being the most recent.

Examples:

Community Choice Aggregation

California

In 2010, Marin Clean Energy (MCE) became California’s first CCA, years after enabling legislation was passed in 2002. MCE serves more than 540,000 customers in 37 different communities across four counties of the Bay Area. The program replaced the communities’ default utility, PG&E, when a state law passed in 2022 requiring all customers be serviced by MCE unless they opt out.

Residents that participate in MCE are given a choice of three different energy options that they can choose from: Light Green (60 percent renewable), Deep Green (100 percent renewable), and Local Sol (100% locally-produced solar energy). California has by far the most solar capacity in the country, and programs like this signal municipal commitment to solar and can help attract additional investment and strengthen local economies.

Since the program came online, MCE has saved its customers over $31.5 million through reduced energy rates. MCE reinvests money into its member communities through residential, commercial, and workforce programs. These include free home energy assessments, rebates for electrification measures, EV rebates, and workforce development opportunities.

Since MCE began, California now has 25 CCA programs with more than 11 million customers across the state. In total, the state’s CCAs have contracted for more than 11,000 megawatts of new clean energy generation.