Let’s be honest – creating a just, sustainable, equitable economy quickly enough to avoid the worst impacts of climate change is going to require a lot of capital for investment. We have about 10 years to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in half, fundamentally changing our economic structures and means of production away from the fossil fuels that they currently rely upon. A shift this large means mobilizing our private and public institutions at a scale we haven’t seen since World War II. But all of this will indeed be money well spent – these investments will reap massive benefits in the form of improved public health, efficient transportation, and more productive and resilient economies. The main question in the short term is how to begin paying for these much-needed investment projects.

Carbon pricing can be a large source of funding for this transition. Not only would pricing pollution raise substantial money to invest in far-reaching, equitable solutions, but it would also help give low-carbon solutions a competitive edge in the market. Here in the U.S., passing a carbon price at levels recommended by the World Bank would raise $3-6 trillion dollars over the next decade to invest in our sustainable future, according to our in-house analysis.

However, a transition that is just cannot be funded on the backs of low-income families. Low-income households are responsible for a very small portion of pollution, yet spend a larger percentage of their income on energy.

Burden of carbon taxation* on households, by income quintile (% of household consumption)

- US poorest

- US 2

- US 3

- US 4

- US richest

*$50/tonne carbon tax in 2030

Source: International Monetary Fund

If not designed holistically, carbon pricing runs the risk of creating regressive outcomes for people and communities that have already been disproportionately overburdened. So, how do we create far-reaching, ambitious carbon pricing policies that protect vulnerable families and small businesses?

There are two ways to use revenue from a carbon price – invest it or return it back to people and businesses.

To put it simply, repayments are about short-term protection, while investments are about long-term transformation.

Revenue-neutral carbon pollution pricing proposals return all revenue, while revenue-positive proposals direct some or all of it towards investment or general government spending. Generally, the public supports using revenue to fund mitigation and adaptation programs – we’ve also written extensively on how to do so equitably.

On one side, revenue-neutral supporters argue that returning all carbon pricing funds back to households and businesses can build support across the political aisle, create progressive economic outcomes, and enable policymakers to achieve far higher carbon prices without adversely impacting vulnerable communities.

On the other hand, supporters of revenue-positive design argue that a price signal by itself will do little to reverse deep existing social and environmental injustices associated with the polluter-industrial economy, and thus investing in equitable climate solutions is a key part of any carbon pricing policy.

These approaches are in fact complementary to each other. A comprehensive approach to economic justice would provide sufficient short-term protections to disadvantaged families while investing in ways that create new pathways of self-determination and economic mobility for entire communities.

Indeed, returning 100% of revenue back to consumers does little to address deep systemic social and environmental injustices that must be addressed in the coming decade. However, investing in equitable solutions takes time. Targeted economic protections for vulnerable families and workers can provide the short-term economic protections needed to justify ambitious carbon prices, while still leaving revenue to invest in long-term, transformative solutions that address systemic social and environmental issues.

What exactly does the right balance of repayment to investment look like? It depends on the program.

Comparing Existing Approaches

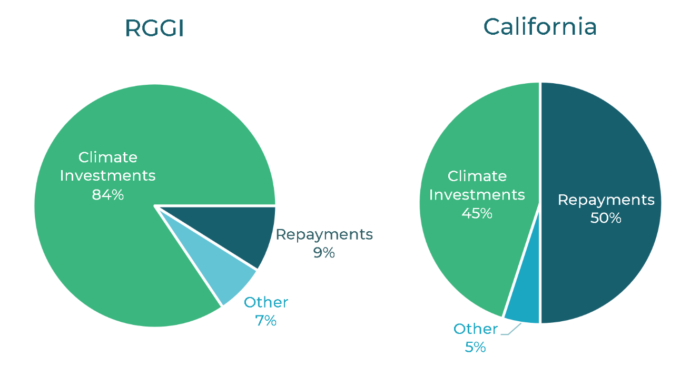

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a cap-and-trade program for electricity sector emissions in the Northeast, directs nearly all revenue towards investment projects such as energy efficiency and renewable energy.

Meanwhile, California’s cap-and-trade program uses a large portion of revenue to protect families and businesses from higher energy costs. It does so through a few different ways – dividends on utility bills, protections for large and small industries, etc. – which amount to about half of their program’s budget.

Use of revenue in existing cap-and-trade systems in the United States

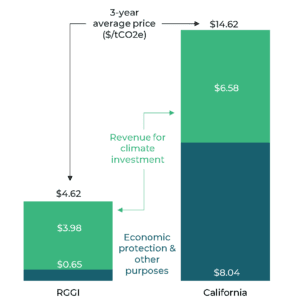

Why the different uses in revenue? First, RGGI’s climate ambition (and resulting carbon price) has been quite low. Carbon prices in RGGI have remained between $1.89 and $7.50 per ton of carbon dioxide, amounting to less than a 0.6% increase on electricity bills. This price increase is completely dwarfed by electricity bill savings due to investment into energy efficiency and renewables, creating net benefits of $4.7 billion to the region’s economy due to the program.

Even though California repays a large portion of revenue back to families and businesses, they are still raising more investment funds from each unit of carbon dioxide than RGGI.

California’s program, on the other hand, has resulted in carbon prices in the range of $10 to $17.50 per metric ton of CO₂ since program launch. As a result, even though California repays a large portion of revenue back to families and businesses, they are still raising more investment funds from each unit of carbon dioxide than RGGI. If repaying a portion of funds helps justify higher carbon prices, then it can in fact lead to greater overall investment revenue than if the program had kept all funds dedicated to investment in exchange for a lower price.

RGGI and California Revenue Use vs. Carbon Price

Despite dedicating a higher portion of revenue to repayments and exemptions, California is raising more money for investments per unit of carbon dioxide than RGGI. Source: Carbon Pricing in a Just Transition (2019)

However, California still has room to improve how these repayments are distributed. A large portion of these repayments are distributed as a flat “climate dividend” on utility bills to all households. While current analysis finds that these dividends are effectively protecting low-income families, the program could create more progressive outcomes by weighing the dividend according to income. After all, higher-income households are far less dependent on the climate dividend than low-income households.

Additionally, a portion of these repayments take the form of protections for manufacturing, petroleum and other major industries in the state. In particular, Energy-Intensive Trade-Exposed (EITE) industries are those that already have an incentive to pursue energy-efficient practices to sell their products competitively on a global market. In California, many of these industries are attributed an “output-based allocation”, which essentially protects these industries from adverse economic impacts while incentivizing more energy-efficient production processes.

However, it is easy for these economic protections for industry to get out of hand. Under the guise of protecting state economic interests, large polluters may have had a heavy influence in developing benchmarks that amount to excessive protections to industry bottom lines. While some level of industry protection may be a necessary compromise to pass ambitious policy design, it is an aspect of repayment that should be critically examined in future programs.

If California had created a more targeted, equitable repayment structure that removes excessive industry protections and repayments to affluent households, they would have freed up an additional $3 to $6 billion dollars to either invest or return to the families and small businesses that need it most.

If excessive protections for corporate polluters are necessary to pass the program in the first place, then there is a larger political problem that needs to be solved. However, this coming decade will require substantially more ambitious climate policy in order to keep us on track for 2030. Our approach to repayment and investment of carbon pricing revenue should balance between short-term protections for vulnerable families and businesses, and maximizing what revenue can be invested directly into climate solutions to create long-term change.