This webinar is part of the State Carbon Pricing Network’s Deep Dive Webinar Series. Each month, we explore a carbon pricing topic in depth, bringing in experts and pushing forward the conversation.

Last week, six Democratic presidential candidates met in South Carolina at the first-ever Presidential Forum on Environmental Justice, focused on solutions to address the needs of the most overburdened and underserved communities around the country. Presidential candidates discussed eradicating environmental injustices around the US; replacing all lead service lines in the country to avoid another crisis like in Flint, Michigan; and allocating funding to the communities that need it most. Yet, carbon pollution pricing did not come up as a potential policy solution to achieve the necessary changes candidates mentioned.

In our latest report, Carbon Pricing in a Just Transition, Senior Research Associate Jonah Kurman-Faber, offers a carbon pricing policy framework that explores the role it can play in a just transition to an equitable, sustainable future. So how exactly can carbon pricing programs improve public health, facilitate sustainable development, foster economic mobility, strengthen resilience, and create new pathways for political self-determination in the communities that need it most? What does an equitable and inclusive design process look like, and how can states put environmental justice at the forefront of climate policy?

Veronica Eady of California’s Air Resources Board (CARB), Eleanor Fort of Green for All, as well as Jonah Kurman-Faber of Climate XChange joined the State Carbon Pricing Network to discuss these questions and what we can learn from California’s experience on cap-and-trade and environmental justice.

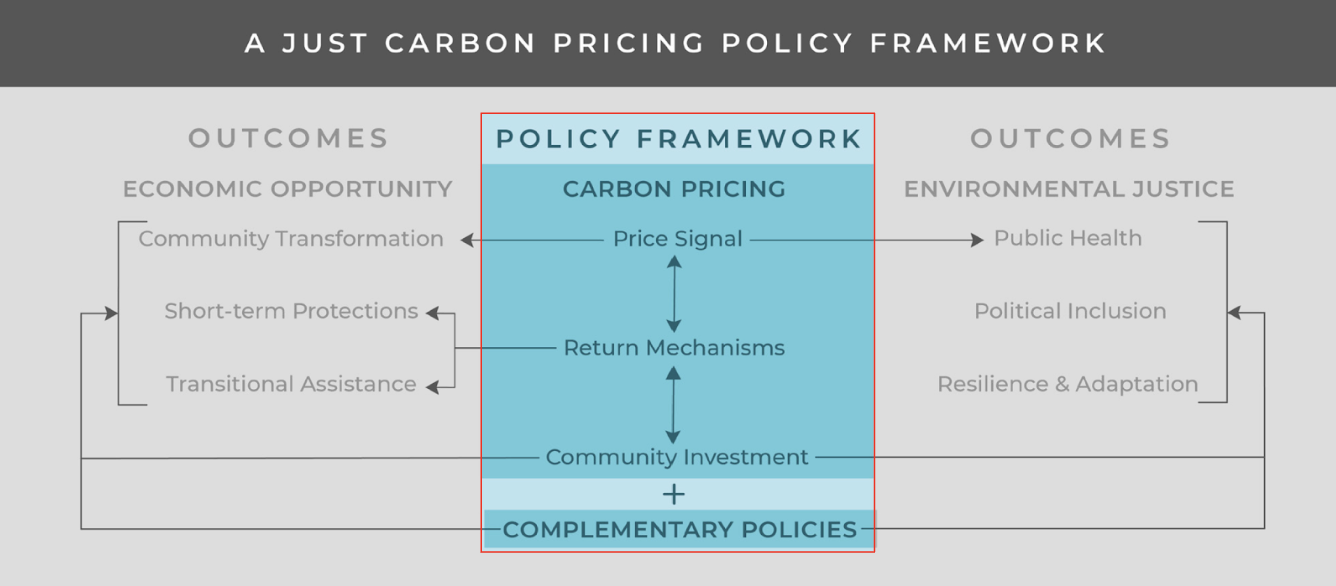

A Just Carbon Pricing Policy Framework

The framework for a just carbon pricing policy is made up of four components — including complementary policies — and six outcomes.

Source: Climate XChange

Carbon price signal

This is how policies make polluters pay, in the form of a carbon fee based on polluters’ yearly emissions, or a cap-and-trade system where polluters submit permits for each ton of carbon dioxide they emit. The price signal also incorporates the sectors of the economy which are covered – under RGGI, the Northeast cap-and-trade program, only electricity is priced, different from California’s program, which is economy-wide.

Kurman-Faber stressed that strong carbon pricing signals are needed for both greenhouse gas emissions reductions and environmental justice. This is the case because first, carbon prices in almost every system are too low to reflect the social cost of pollution — especially once local pollutants and health impacts are included in the estimate. Second, higher prices raise more investment revenue that can be directed to programs that tackle more deep and systemic aspects of environmental injustice. Third, “the higher the carbon price is, the more likely that it would impact the behaviors of polluting industries in [disproportionately burdened] communities,” he added.

Revenue return mechanisms

These are any kind of repayment or short-term economic protection for people and/or businesses. Kurman-Faber stressed that a balance of revenue and investments is necessary to ensure that the “just transition is not paid for on the backs of low-income families.” Low-income households are responsible for a small percentage of emissions in the U.S., so a portion of revenue can be used to repay vulnerable households to create progressive outcomes and eliminate the financial burden of higher energy prices.

Community investment

Investment revenue is typically used for projects that further reduce greenhouse gas emissions, or address other important community needs

“Investment is a flexible concept,” Kurman-Faber said, “so it can be designed to address all the economic opportunity and environmental justice outcomes [of the framework].” The framework provides context for how states and communities can set up processes to decide what local investment projects should be funded. It includes modernizing datasets to define disadvantaged communities, directing a percentage of investment funds to directly benefit those communities, and develop methodologies to assess projects on their results, such as GHG reductions, job creation, and public health impacts. Across all these processes, Kurman-Faber stressed transparency and inclusive governance structures that give communities a direct influence over selected investment projects.

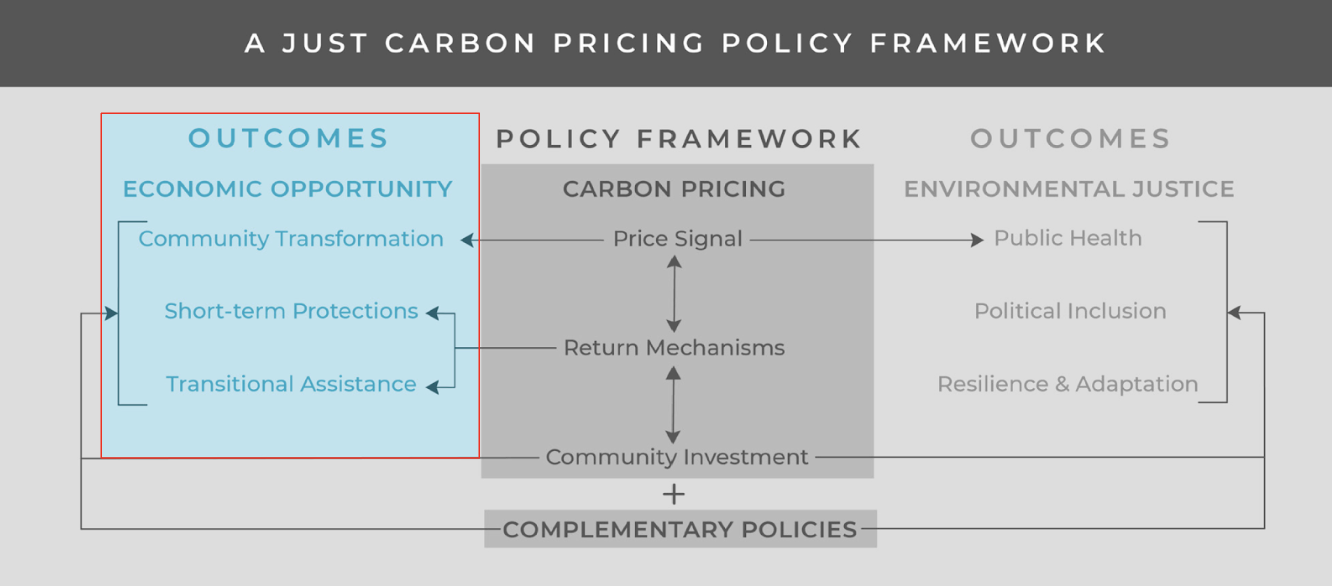

These carbon pricing components can create six outcomes that contribute to economic opportunity and environmental justice.

Source: Climate XChange

Economic opportunity

This usually focuses on economic material outcomes, according to Kurman-Faber. Within this category, community transformation addresses the question: “How can we sustainably develop the communities that need resources the most?” Carbon pricing programs need to be developed to provide durable and tangible benefits, such as job creation, economic mobility, transportation access, and other co-benefits directly to people in order to thrive in place.

Community transformation doesn’t happen overnight, however, so short-term solutions must also provide the necessary economic protection to vulnerable communities. Short-term protections, such as rebates, serve to cushion individuals and households from changes in the cost of living. These protections must be designed progressively to ensure that money flows to the people who need it most. Transitional assistance focuses on replacing the resources, wages and tax revenue for communities and families that are currently dependent on the fossil fuel industry and need new livelihoods in the clean energy future.

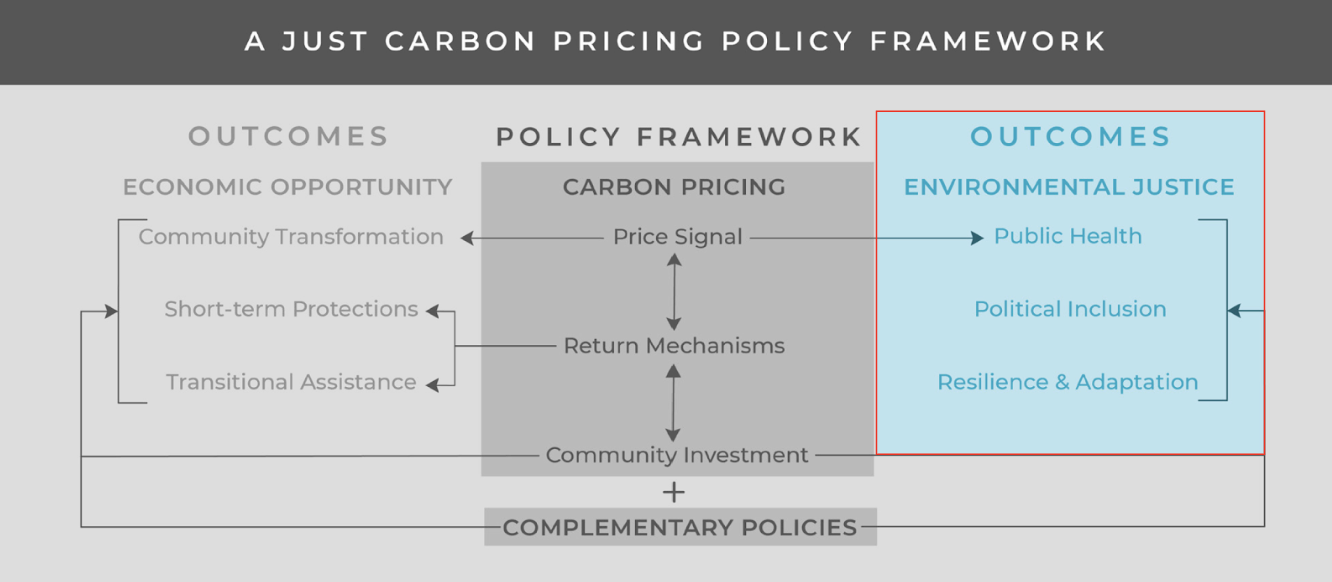

Source: Climate XChange

Environmental Justice

Outcomes in this category pinpoint the impacts on people related to greenhouse gas pollution and larger systemic issues that communities face. Environmental justice incorporates addressing health and environmental impacts from climate change, and seeks to increase the political inclusion and self-determination of communities that have historically been under-served and overburdened. Political inclusion is “empowering local organizations and governments to facilitate the just transition in their local context,” Kurman-Faber explained. Along with this, the interests of communities must be integrated into all aspects of the policy design.

A major focus of environmental justice advocates is the public health impact of greenhouse gas emissions and local pollution. Low-income communities and communities of color experience disproportionate impacts from local pollutants that cause respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and even premature death. Climate solutions must address the distributional impacts of pollution in addition to reducing aggregate greenhouse gases rapidly.

The communities most vulnerable to climate impacts are often those with fewer resources to address them. A just framework for carbon pollution pricing creates the necessary resources for resilience and adaptation in communities that need to deal with impacts and disasters caused by the climate crisis.

What about California?

Kurman-Faber’s research examines California’s cap-and-trade program and the state’s efforts to incorporate economic opportunity and environmental justice into their climate policy. In 2013, California implemented the first state-level, economy-wide cap-and-trade program in the United States. About half of the revenue is returned to households and vulnerable businesses, and another 45% is invested in programs to further reduce greenhouse gas emissions. To date, this program has generated almost $12 billion in auction proceeds.

A certain percentage of investments must go towards funding projects in disadvantaged or low-income communities and households. By law, 25% of funding must be allocated for projects in disadvantaged communities, defined by the California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA), and an additional 10% must be allocated for projects in low-income communities.

In order to define disadvantaged communities, CalEPA combined over 20 socioeconomic and environmental factors into a holistic “CalEnviroScreen” score; the top 25% scoring census tracts – meaning the areas that experience the worst impacts – qualify as a disadvantaged community for California Climate Investments. Kurman-Faber praised California’s use of modern data to define and determine which communities are disadvantaged for the purpose of more effective environmental justice policy. He noted that many states lack similar data practices to understand which communities need to be prioritized, and suggested that carbon pricing can be used as an opportunity to “update these data practices and then circulate them throughout all their climate policies.”

To date, California has implemented forty-five programs that fund energy efficiency, low-carbon transportation, and sustainable housing projects, among others. The majority of California Climate Investments are going towards transportation programs, but a smaller fraction are invested in transformative projects in California’s most impacted communities. An example of the potential role investments can play in is the Transformative Climate Communities program. The top 5% of CalEnviroScreen score census tracts qualify for funding; these are the “worst-polluted, most underserved, overburdened communities in the state,” Kurman-Faber said. The programs allow the community to decide what changes they need to see in their neighborhood through dense funding for place-based initiatives.

What else is going on in California?

To have a successful, transformative, equitable solution to the climate crisis, there must be a “comprehensive, holistic approach” that includes complementary policies to carbon pricing. Governments must be intentional about what role each policy will play, because carbon pricing is not a “one-size fits all solution for any given state or nation,” Kurman-Faber explained.

Veronica Eady, Assistant Executive Officer for Environmental Justice at the California Air Resources Board, spoke about the other programs that the California Climate Investments funds. In 2017, AB 617 established the Community Air Protection Program, which was created to address local air pollution issues. There is a community air monitoring component of the program that collects data from air pollution sensors to create a community-level emission inventory and put together long-term plans to reduce emissions in those communities. This program highlights the importance of community engagement in climate solutions, “bringing local residents to the table with representatives from CARB and local air districts to develop and implement plans,” Eady explained.

AB 617 programs have been allocated almost $1 billion to incentivize industries to transition to cleaner technology, transportation, and equipment. Some things that can be funded are determined by community steering committees across the state. The state legislature also appropriated $25 million for local organizations to increase awareness and educate communities about CARB’s programs, as well as environmental literacy.

Community engagement is key

Eleanor Fort, Senior Campaign Manager at Green For All, highlighted the importance of community engagement throughout the design and implementation processes. “The only way to get equitable outcomes is to start with an equitable process from the beginning,” she stated. Identifying who is disproportionately impacted, as well as how they are impacted — economically, by co-pollutants, related to transportation — is one of the first steps in an inclusive design process. Once these communities are engaged, states must have “a process of political inclusion, and directly funding and empowering communities to give them the capacity to have that self-determination to be at the table,” Fort explained.

CARB and local Air Districts also have policies in place to compensate the individuals working to improve California’s programs. Steering committee members typically get a stipend for the meetings they attend, and food and child care are provided. CARB is trying to compensate communities for helping to build the community air pollution inventory.

What can we learn from California?

But, these are all “decisions made in California for California,” Kurman-Faber said. He also pointed out that California’s system is not perfect – the Transformative Climate Communities program only receives about 2% of total California Climate Investment dollars. Additionally, California gives a flat rebate to all consumers, including affluent households and wealthy businesses who don’t necessarily need it; about $2-3 billion could be freed up for transformative programs if California had a more progressive rebate system.

The Transportation and Climate Initiative program design is currently underway in the Northeast, and one of the main things advocates hope to see in TCI is “adopting some of the lessons that California has learned and innovated and improved upon […] over the past few years” to incorporate equity into the design and implementation from the start is essential, according to Fort.

“Having that be an inclusive process, where everyone gets to understand that knowledge and add their input into the [design] process […] is something that absolutely needs to be done for carbon pricing,” Kurman-Faber concluded.